The opening scene of Party Girl has RuPaul’s former roommate, Lady Bunny, in her trademark cotton-colored bouffant wig, on the landing of a staircase, overlooking the ass of a woman who is on her hands and knees searching for the “little plastic baby boy” that fell from Lady Bunny’s ear and without which, “I cannot make my big entrance.” It is the perfect cool open for a movie about a 90s club kid named Mary (Parker Posey) who is always poised to party and always on everyone’s ass about how she’s missing something, while the Sisyphean stairs of life stretch out before her. As her roommate eloquently puts it: “You’re telling me that if your name was Syphilis and you spent your whole life lugging a rock up a hill you wouldn’t be miserable?”

Party Girl has been one of my movies—you know, those movies you quote constantly and refer to constantly, often to the irritation of everyone around you because it’s irritating—since it came out in 1995 when I was 15. It’s less about the premise itself—a party girl wants to get her life together and become a librarian, which even director and co-writer Daisy von Scherler Mayer admits is as “thin as an envelope”—than literally everything else about it, including Mayer’s own mother, Sasha Von Scherler, killing it as Mary’s patronizing godmother Judy Lindendorf. (On Mary’s inability to master the Dewey Decimal System, she hollers: “A trained monkey learned this system on PBS in a matter of hours!”)

This is a movie steeped in queer '90s New York club culture because everyone who made it—from co-writer Harry Birckmayer, who worked on Paris Is Burning, to costume designer Michael Clancy, who borrowed Mary’s rhinestone shorts from Todd Oldham, to drag music genius Bill Coleman—was steeped in that culture. So when Mary says “Na-ta-sha!” and Natasha Twist stops in the middle of the dance floor and does some weird Mr. Peanut style choreo, and then Mary gets up and strikes a number of poses as Twist continues to vogue with and around her, or when, mid-conversation, Mary yells various in-jokes to passing friends—“He-he-hello!”—like the green-haired It Twins (a “big get” for this humble production of $150,000), you may understand it as little as I do, but the casual insanity is so seamlessly offered up you can’t help but embrace it.

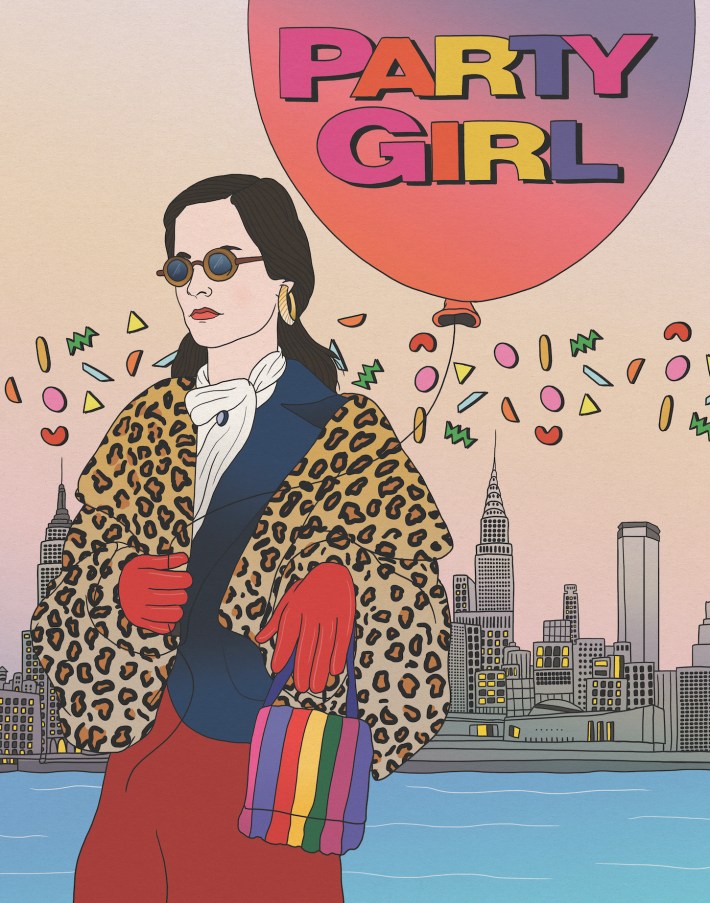

What if you made a movie where the goal at the end is not that the girl gets the guy, but that she gets a job? Party Girl’s filmmakers thought. So the girl was key. And Posey as Mary—the product of “a mother who was a woman with no common sense” and “a father who was a man without a conscience”—is at the very least half the draw of this whole enterprise. And a lot of that seems to be because Posey herself embodies a form of drag. It’s baked into that nonchalant, slack-wristed, high-heeled mince of hers, the way she talks like a valley girl on sleeping pills (“I think I’m an existentialist. I do.”), the thick spread of irony coating everything (“Do you realize how broke I am? What do you want me to do? I don’t have a job. I’m a loser. Shoot me.”), and always that core of impishness (see the montage of her learning the Dewey Decimal System while cartwheeling over a pile of books—Posey suggested that). Then there are the clothes. Posey apparently said the role belonged to her because she had “80 pairs of shoes,” and although she doesn’t wear all of them, she does show up in one scene in four Oldham shirts at once. Mary’s outfits are more curated than anything else in her life (except for her lunch order: “A falafel with hot sauce, a side order of baba ganoush and a seltzer, please”). This is a woman who seems like she wouldn’t be out of place at one of Gatsby’s parties, and yet at the same time would stage her own parody of it.

I watched Party Girl this time around on the Criterion Channel, which looked 10 times better than my DVD, because of Fun City Editions’s recent 4K restoration. I only watched it there because I couldn’t get my hands on the boutique label’s new Blu-ray in time (I was late to ask for an early copy—it’s out March 28). I asked Fun City founder Jonathan Hertzberg why he chose to release Party Girl in high definition now, and he explained, via email, “That the film’s main creative forces were women and/or LGBTQ people, and that the film very organically espouses an attitude of inclusivity, while being incredibly fun and positive throughout … these are things we can still use and need today.” He noted Party Girl also fits neatly into his label’s archive. Fun City was apparently the nickname of the fucked-up New York of the 60s to 80s, and Fun City Editions has a soft spot for neglected local time capsules with exceptional soundtracks. Sorry if this sounds like an ad, my expositional skills need work. (FYI, if this were an ad, I would be so rich off my job in advertising I wouldn’t care about my expositional skills.)

But there remains a question (besides: What the fuck?) that I have always had which is: Why the hell would anyone choose this to be the first movie to premiere on the internet? Because that is in fact what happened in tech mecca (at the time) Seattle on June 3, 1995, at 6:00 p.m. PST at the offices of the web hosting company Point of Presence. On the same night Party Girl was opening at the Seattle International Film Festival (SIFF), Posey sat in a swivel chair and said in her trademark sleepy drawl: “This is very exciting. I want to encourage everyone to still pay the $7.50.” Then she turned around and pressed a button to start the stream (which was being simulcast at The Egyptian theater’s premiere). But remember, this was 1995. Apple could run short videos on Quicktime, but Netflix hadn’t even been invented yet. “We were all curious to see a film streamed on a computer,” Carl Spence, who ran SIFF at the time, told me via email. That year, a tech company called Silicon Graphics was sponsoring the festival and their servers happened to be powerful enough to stream a film live, so that is what SIFF set out to do—to premiere a film at the fest and online at the same time. But why Party Girl? Why not Safe? Or, like, To Die For? “The film company was most interested in the publicity it could garner for the film,” Spence said. “I was most interested in the technology.”

A former film critic named Lucy Mohl was hired as the “emcee” to make Posey feel comfortable. SIFF had provided seed money for Mohl to launch film.com and as she was using the Point of Presence Company (POPCO) offices, that became the site of the Party Girl broadcast. But Glenn Fleishman’s web hosting company operated on only 1.5 Mbps (for comparison, the average now is 42.86 Mbps), which was already expensive as hell. “It was better than a bunch of tin cans connected by string,” he said. “But there wasn’t much of it.” For the projection, they chose an online video-conferencing client, CU-SeeMe, in what Mohl called a “really elaborate setup.” They then filled the POPCO offices with people they knew to make it look a little less like an office and more like a party. An NBC News crew even showed up. “Being on national news in 1995 was really cool,” Fleishman said. He was wearing his “fanciest suspenders,” and recalled Posey arriving in a “great herringbone” suit and said she was very nice. “It wasn’t, Oh, no, what am I doing with a bunch of nerds? or whatever,” he said. Posey, who said only a couple years ago that she couldn’t remember the event, was only there for about 15 minutes—to send the video live—and then she was gone.

“I was like, ‘This is the lowest fidelity movie that will ever stream over the internet,’” Fleishman told me. “Officially, I think that’s proven to be the case.” Mohl compared the way Party Girl looked online in 1995 to Eadweard Muybridge’s Horse in Motion. “It was the idea that we were doing it that was so exciting,” she said. “The end result was for a relatively small audience to marvel that it was attempted.” Spence was chuffed though: “It was pretty fantastic to watch it being streamed live from the studio and then to see what it looked like on the computer receiving the signal.” Though Party Girl’s distributor told NBC News the “crudeness” of the broadcast meant it was no real threat to cinemas just yet, Mohl could see a future in which streaming took over—she was less concerned about the practicalities. Fleishman, on the other hand, thought that the most we could expect was that audiences in the future would pay to watch an online broadcast. He couldn’t conceive of a universe in which Party Girl streamed on a site like Criterion’s, among so many other films, and so many other streamers. “We’re like, ‘Oh, well, if you did an event, you’d have, like, a million people on 1,000 Internet service provider networks,’” he said. “But you would never have a million people streaming a million different things. That’s ridiculous.”