With scant guidance for how to handle copyright requests for AI-generated works, the law is playing catch-up. As copyright offices around the world have consistently denied protections to AI art, you run across phrases like “the copyrightability of the monkey’s work,” as judges ruling on lawsuits are forced to rely on case law related to crested macaque photographers. And that’s not even close to the weirdest precedent cited.

The 2023 case Thaler v. Perlmutter dealt with a copyright battle over an AI-generated picture. In ruling for the U.S. Copyright Office and its refusal to grant copyright protection, District Court Judge Beryl A. Howell wrote that a copyright has never been granted to “a work originating with a non-human.” To support this, Judge Howell called back to an 83-year-old case, Oliver v. Saint Germain Foundation, which involved a legal battle over a book purportedly dictated by an ancient Atlantean spirit. The story behind that book, and that case, is worth telling on its own merits.

Frederick Spencer Oliver lived two lives. His public life was one of failure. Failed at turkey farming. Failed at stenography.

The private Frederick Spencer Oliver was a failure, too. Failed at publishing the one book he did write. Failed to oversee the cult he so desperately wished for. Failed to entice the one woman who he believed could make him cosmically whole. But in his failure, he created a movement.

Born in Washington, D.C., shortly after the Civil War, Oliver’s family moved to Ballard, Calif., just north of Santa Barbara. There, as an only child, Oliver received all his mother’s attention, formal education taking a back seat to her indulging his flights of fancy. He seemed to adapt to the real world when he eventually entered it: college, and a career following in the footsteps of his father by becoming a reporter. Oliver mostly covered the agricultural life of the Santa Ynez Valley, filing stories on irrigation disputes and olive grove blights. He married and had two sons. To all outward appearances, his was a normal and respectable life.

But at age 17, Oliver had started hearing a voice in his head. This was Phylos, an ancient, spiritual master from “Thibet.” Phylos, Oliver wrote, wanted “to make me his instrument of the world”—an instrument he quickly became with Phylos imparting the true nature of humanity, spirituality, and all the cosmos.

The teenage Oliver became sullen and withdrawn. His parents fretted over this change to their happy-go-lucky boy. After weeks of inquiring what was bothering him, Frederick finally spoke up, telling them about the astral Tibetan in his head. Surprisingly chill about this revelation, the Olivers asked to meet this Phylos fellow. Through Frederick the spirit spoke to them, telling stories of his youth in Atlantis and of esoteric Christian morality. Soon, neighbors were coming by to hear these teachings for themselves.

Phylos took things to the next level by dictating to Oliver the material that would become the book A Dweller on Two Planets, an arduous process thanks to Phylos’s mercurial editorial choices. By 1886 the manuscript was completed; for the next 13 years, Oliver tried and failed to find a publisher. In 1894 he may have been close to a deal, but the train carrying the manuscript to the publisher in New York City was robbed, derailed, and set ablaze.

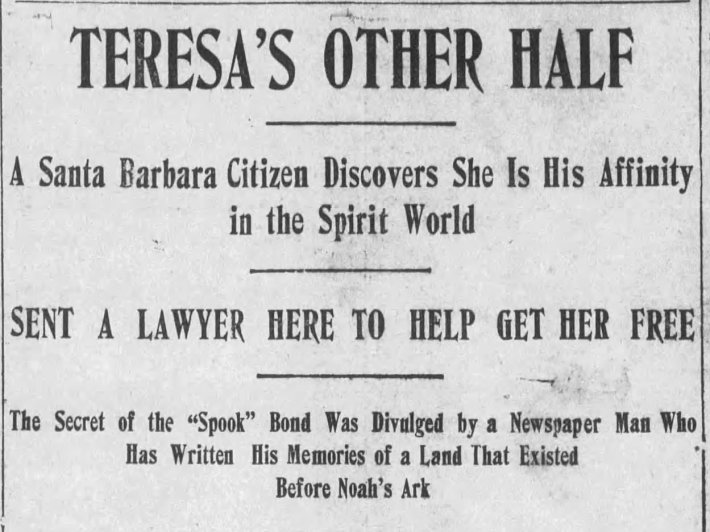

The public and private Olivers would collide openly and humiliatingly in 1899, the last year of his life. That January, Oliver read an interview with Teresa Kerr, who was sitting in a Los Angeles jail for shooting her estranged husband inside City Hall.

A former sex worker, Kerr had married a client of hers, George King, who came from a prominent local political family. King’s friends warned him that having Kerr as a wife would hurt his political ambitions, so he ghosted her shortly after Christmas, 1898. Distraught, Kerr went to City Hall, where King worked in the city’s engineering department, with the intention of taking her own life in front of him. She raised her .32 Smith & Wesson. He snatched at it. In the scuffle the gun went off, fatally wounding King.

The story enraptured California, and as Kerr sat in jail, she became a folk hero. Sex workers across the city pooled together funds for her defense. Women from all over wrote letters of support, including Edwina Oliver, Frederick’s wife. She pleaded with Kerr to come and live with them after her trial, to start her new life as a member of the Oliver family:

“I want her, I need her, and she needs me! Los Angeles, so fair to many, must be a vista of Hades to this poor soul-sick girl … shall we not go down the Stream of Time together, both our lives the better for our companionships, and together go to One who bids all the weary to come to Him? I have found Him and to Him would I take her.”

This was the first in a series of red flags from the Olivers as they tried to insert themselves into Kerr’s trial and life. Attempts included: Frederick’s mother trying to adopt the 25-year-old Kerr; Frederick’s lawyer/literary agent/Phylos disciple trying to bribe his way onto Kerr’s defense team; and finally, Frederick himself showing up in Kerr’s lawyer’s office to inquire about her, saying he had a “cousinly” interest in her.

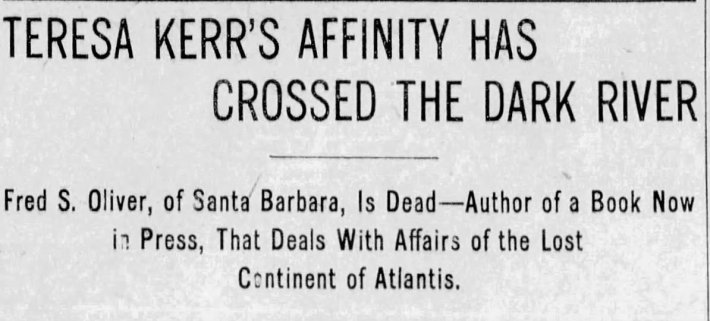

Only after Kerr’s acquittal did the Olivers’ efforts come out in the press—to public ridicule. Not long after, Frederick suffered an internal hemorrhage as a result of cirrhosis of the liver. He spent agonizing months laid up, before dying on Nov. 15, 1899.

In the coverage of Oliver’s interest in Kerr, it emerged that he had felt that she was his “affinity.” Frederick’s cosmology—dictated by Phylos—held that each person is but a half only made whole when they find their other half, their affinity. For Frederick, Kerr and not his wife Edwina was that half who had traveled through the ages from Atlantis to California to finally complete him. Her rejection of his advances made his final year even more painful. Uniting with her, he believed, was his one chance to bring A Dweller on Two Planets to life.

A Dweller on Two Planets is a weird and tedious book that, I promise you, sounds a lot more interesting than it is. Zailm is a poor kid from rural Atlantis who strikes it rich and works his way up through society until he eventually becomes the Secretary of Records for the Atlantean Empire. He manages to get himself into a love triangle with his adopted sister and a princess. That goes about as well as you’d expect: When the princess finds out about the sister, she gets stabby and is turned into a statue for her transgressions. Zailm broods around Atlantis on his vailx, a submarine-like vessel, for a few weeks before pulling an Obi-Wan and blinking out of this mortal plane.

The second half of the book has Zailm reincarnated as Walter Pierson, an eight-fingered Civil War veteran who comes to Northern California after the war. Pierson helps a troubled, alcoholic sex worker rediscover her passion for art. Then he meets a mysterious Chinese man, Quong, who psychically subdues a mountain lion and takes him inside Mount Shasta, where other ascended masters are meeting. They initiate Pierson into their society and beam him to Venus, where he turns into Phylos and undertakes a magical mystery tour of esoteric Christian secrets of the universe. After a couple of weeks on Venus, he comes back to this world; his disappointment must have been palpable. More Earthly travels ensue, and he reconnects with the woman he helped in California. They marry and almost live happily ever after but perish in a shipwreck.

A Dweller on Two Planets was finally published in 1905, after Oliver’s death, thanks to the tenacity of his mother raising funds for the publishing costs. Not an immediate success, the book became a word-of-mouth occult hit by the late 1920s, a time of intense interest in spiritualism and mysticism. Oliver’s book was a major influence on the idea that something strange was going on inside of Mount Shasta: In the ‘20s and ‘30s, a series of articles and books were written about Lemurians who lived within the mountain and shared some suspicious similarities with Oliver’s ascended masters. Others reported running into Phylos around the mountain. All of this created a golden age of weirdness in and around Mount Shasta, which it has not been able to shake: Today, the mountain and the towns surrounding it stand second only to Sedona as the alternative spiritual center of America.

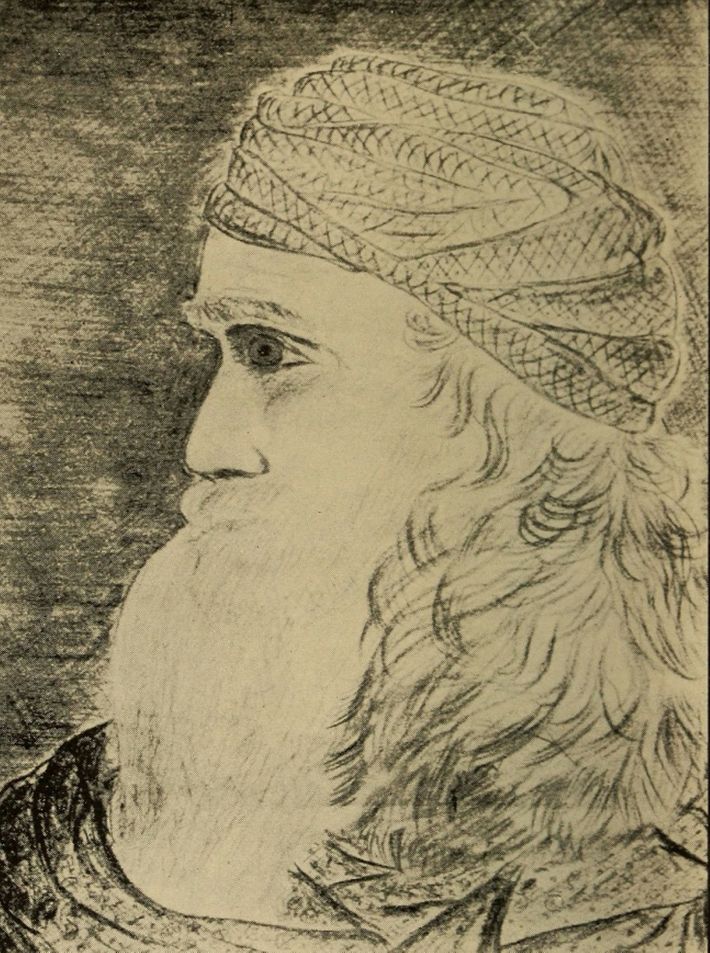

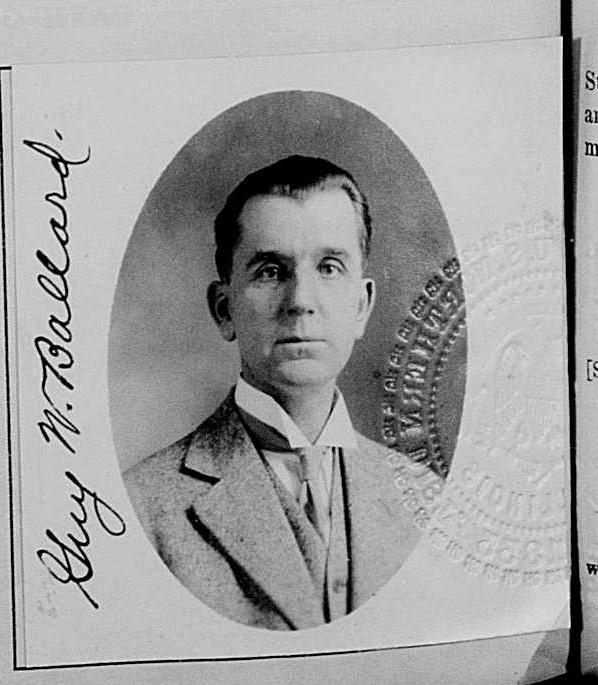

One of the most publicized encounters at Mount Shasta during this time was that of Guy Ballard. In 1930, the Chicago-based Ballard was staying nearby while on some unspecified “government business.” On one walk through the woods, a dreamy character approached, introducing himself as Saint Germain, and gave Ballard a creamy, restorative liquid. Saint Germain then took Ballard on a whirlwind astral tour similar to that in Oliver’s book.

Ballard made this encounter the foundational event in his budding cult. Along with his wife, Edna, he ran the “I AM Activity Movement,” which barnstormed America throughout the 1930s and built a sizable following, all in the service of elevating Ballard to the status of an ascended master like Saint Germain, Jesus, and Phylos—and raking in as much money as possible.

A liking for money had gotten Ballard into a bit of trouble before his ascension. Possessing a natural charm that made little old ladies hand over their life savings, Ballard had run several con jobs around selling stocks in non-existent oil companies and gold mines. The Chicago District Attorney had caught wind of this fraud and indicted Ballard; he skipped town and headed for California, this apparently being the “government business” he was on.

With Guy on the lam, Edna Ballard immersed herself in esoteric teachings while working at her sister’s occult bookstore. She led classes on a number of esoteric writings, from A Dweller on Two Planets to Theosophical works by Helena Blavatsky, Annie Besant, and Alice Bailey, as well as writers like Baird T. Spalding and William Dudley Pelley. She borrowed freely from all of these as she began constructing the backstory to turn Guy into a figure for worship.

Not content with borrowing just Pelley’s ideas, the Ballards also sought to steal members from his fascist organization. Prior to turning to politics, Pelley had been a celebrated author and screenwriter who abruptly shifted gears to esoteric matters after being visited by a mystical being “while studying the question of race.” He began mixing his new metaphysical beliefs with white supremacism. Throughout the 1930s, he railed against the Jewish influence in government while praising Hitler and Mussolini, going as far to emulate them by creating his own group of toughs, the Silver Shirts, styled after Hitler’s Brownshirts.

Pelley ran afoul of the U.S. government in the mid-’30s and had to step back from public life. His loss was the Ballards’ gain as they raided Pelley’s group, luring many of the Silver Shirts and the treasurer of the organization to join the I AM Activity Movement. With this new influence, Guy and Edna pivoted their message to be more vocally patriotic and Christocentric. Where before Guy had been blessed by Saint Germain to lead others to spiritual awakening, now Jesus spoke directly to Guy, telling him that Saint Germain had come to America to help him combat the evil forces working here to undermine our freedoms. Blond-haired, blue-eyed portraits of Jesus and Saint Germain appeared on stage between a pastel-suited Guy and gowned Edna. Each meeting began with an announcer exclaiming, “We must save America!” They put on quite a show, with busty ushers and garlanded Christmas trees gussying up the quasi-fascist spiritual revival crisscrossing the country.

As I AM Activity gained traction, donations filled the coffers of its associated business entity, the Saint Germain Foundation. This enabled the Ballards to set up permanent temples; you can still find I AM Reading Rooms in places like Seattle and Mount Shasta.

On the spiritual side, the Ballards preached celibacy, avoidance of tobacco and alcohol, and that you shouldn’t eat anything with a face. They believed in the divinity of all through thought and will, and Guy embodied this philosophy. The light charging his body made him indestructible, so when he died in December 1939 of heart failure, it came as a shock to the movement.

The second blow occurred in 1940, when Edna and others in the organization were convicted of fraud. Splinter groups formed including the Summit Lighthouse, which morphed into the Church Universal and Triumphant (CUT) led by Elizabeth Clare Prophet that was popular in the 1970s and 1980s. Disgraced General Michael Flynn was caught plagiarizing Prophet in a speech where the only significant change he made was turning “I AM” into “WE WILL.”

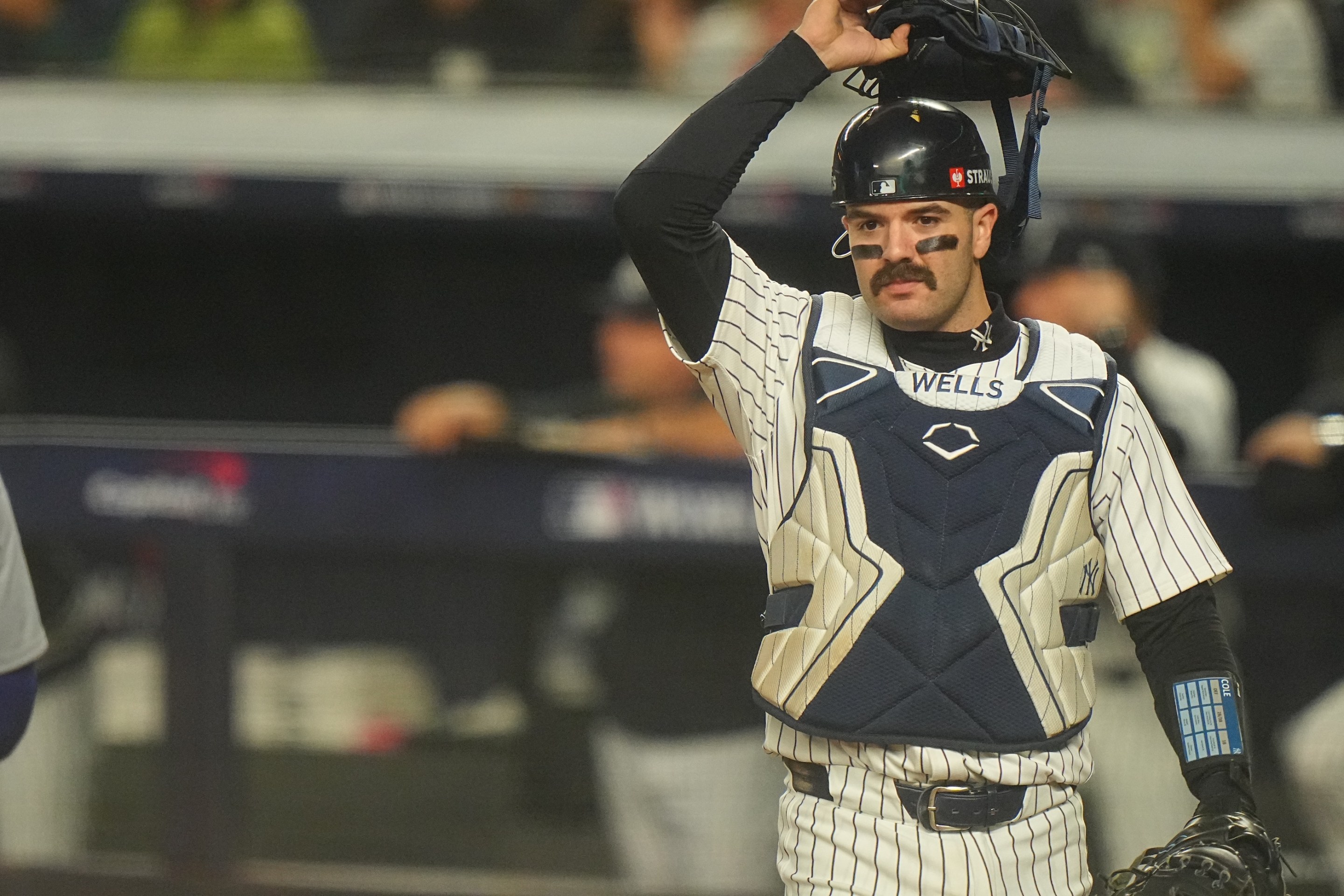

The “I AM” of the I AM Activity Movement, capitalization and all, was just one of the Ballards’ many direct rip-offs of A Dweller on Two Planets, many of which were middle-school book report–level plagiarism of only changing a word or two. For example: In Dweller it’s a mountain lion that gets tamed, while Saint Germain tames a panther. This did not go unnoticed by one of the sons of Frederick Spencer Oliver, who filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against the Ballards’ organization (Oliver v. Saint Germain Foundation), at the same time that Edna and others were on trial for fraud.

Oliver’s son lost the case. What gave A Dweller on Two Planets its authenticity, and its popularity, was its purported authorship: that it was solely dictated by Phylos and not written at all by Oliver. Facts cannot be copyrighted, and the judge wrote that “if we accept Oliver’s statements as true and not fiction, how can we say that [Ballard] ... was any less truthful and sincere.”

This granted A Dweller on Two Planets a second life as case law. It became a cornerstone for the doctrine of “copyright estoppel,” the legal equivalent of no take-backs. It holds, broadly, that if you present something as a fact—like asserting that Phylos had written the book—you can’t then turn around when it’s advantageous for you to say it was entirely fictional—like admitting that no, actually, Frederick Spencer Oliver made it all up, and he’d like to own the copyright now. Houts v. Universal City Studios, Inc. and Arica Institute, Inc. v. Palmer would go on to cement the Oliver ruling in the case history of copyright estoppel, while Garman v. Sterling Publishing Co. and Urantia Foundation v. Maaherra applied the Oliver ruling to similar cases of communication via spirits.

Oliver made its most recent appearance under slightly different circumstances in Thaler v. Perlmutter, which involved an artist’s attempt to copyright an AI-generated picture. When the copyright was denied, the artist sued the Director of the U.S. Copyright Office, Shira Perlmutter. Judge Howell’s decision contextualized Oliver as one in a series of cases concerning whether channeled beings like Phylos, Ramtha, or Seth, or any otherworldly spirit, can own intellectual property attributed to them. They cannot. Nor can any “non-human,” Judge Howell wrote. This gives channeled spirits and curious monkeys, at the moment, the same legal standing as generative AI. And it's all thanks to the efforts of some failed cult leaders, a bunch of wannabe fascists, and the dwellers of long-lost Atlantis.