Early in the fourth quarter of a nationally televised game in November, Los Angeles Lakers wing Cam Reddish was whistled for a shooting foul on Oklahoma City Thunder guard Ajay Mitchell. As Mitchell stepped to the line, however, ESPN viewers were shown a replay indicating that Reddish never actually made contact with Mitchell on the play. The broadcast then cut back to the action in Los Angeles, where Mitchell’s first free throw skipped off the rim and out.

“Uh, ball don’t lie, I guess?” ESPN play-by-play announcer Marc Kestecher quipped.

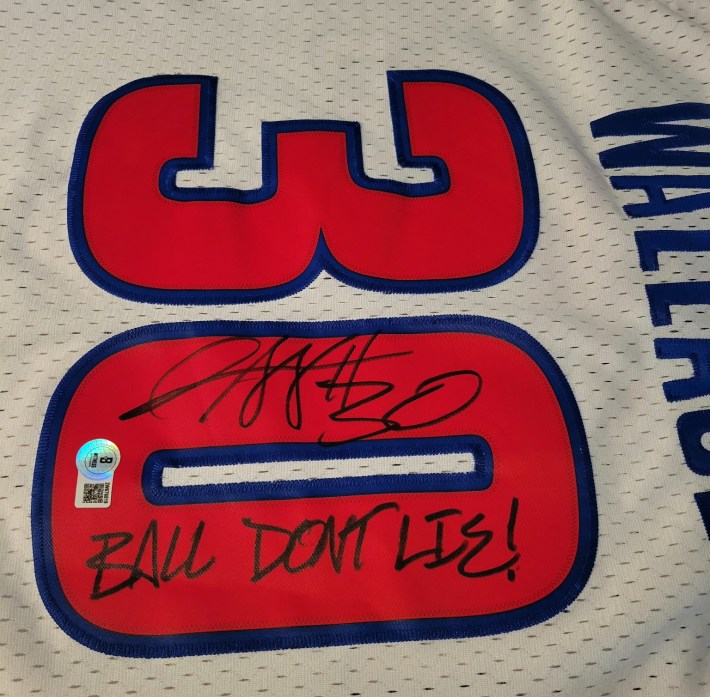

Twenty years have passed since Rasheed Wallace popularized the phrase, barking it since the 2004-05 NBA season to the delight of fans, the ire of referees, and the rehabilitation of his own reputation. Shorthand for the service of karmic justice, often invoked in a smug told-you-so tone, the words remain heard at all levels of the game, from playgrounds to pro arenas. But “Ball don’t lie” has evolved from being an aggrieved athlete’s on-court motto, and achieved wider cultural relevance.

There was the 2008 movie Ball Don’t Lie, starring Grayson “The Professor” Boucher of And1 Mixtape Tour fame, and the similarly titled novel on which its screenplay was based. Yahoo Sports once published NBA news and analysis on the popular “Ball Don’t Lie” blog. A defunct Ball Don’t Lie podcast was co-hosted by ex-quarterback Johnny Manziel and recording artist Michael Seander, who performs as Mike., released the single “Ball Don’t Lie” in 2023.

Like any enduring adage, “Ball don’t lie” has mostly ridden forth through history on the sound waves of those who keep saying it—in this case, whenever a questionable decision from some referee or pickup opponent is promptly followed by a missed free throw, a turnover, or some other sign of a wrong being righted.

“It’s still here to this day, alive and well,” Orlando Magic guard Gary Harris told me this past December. “Everybody’s quick to say that, for sure, especially if someone misses a free throw. I said it growing up. I’ve said it in the league. I’ve probably said it this year.”

Despite the credit that Wallace rightfully receives for making “Ball don’t lie” mainstream, the retired power forward wasn’t the first NBA player quoted as saying it. Per newspaper archives, that honor belongs to former Los Angeles Clipper Corey Maggette, after a February 2004 game in which Maggette fouled the Milwaukee Bucks’ Michael Redd on a three-pointer with 0.1 seconds left and the Clippers ahead 105-102, only for Redd to blow two of his three free throws to cost the Bucks the game.

“The ball don’t lie,” Maggette told reporters in the locker room at the time, via the Associated Press. “So, that’s the end of that. There’s nothing else to say.”

Wallace wasn’t far behind, earning his first print mention later that season in the Chicago Tribune, following his deadline trade from Atlanta to Detroit. Referring to the player’s past reputation as that of an “angry young man” who “made the old Pistons Bad Boys look like choirboys,” columnist Sam Smith posited that Wallace had turned over a new leaf. As evidence, it cited how the player had hollered “The ball don’t lie” following an opponent’s missed free throw. “Just havin’ fun," Smith concluded. "Like this very good Pistons team.”

After that very good Detroit team beat the Lakers in five and won the 2004 NBA Finals, “Ball don’t lie” soon came to symbolize its progenitor’s revamped persona. “Wallace is an entertainer, down to the way he commits a foul, argues with the official, then screams, ‘The ball don’t lie!’ when the opponent misses a shot,” The Oregonian wrote in March 2005. Added the Detroit Free Press that May: “His ‘Ball Don’t Lie’ phrase … is a favorite among his teammates.”

“Ball don’t lie” was catching on with Pistons fans too, among them Detroit-area native Jack Crawley. Before the 2005-06 season, a then-15-year-old Crawley went with his dad to watch the team’s annual open practice at the Palace of Auburn Hills, arriving early and posting up outside the player parking lot alongside a group of similarly aged autograph-seekers. In his hands was a hardcover book commemorating Detroit’s '04 title run, which Crawley thrust out as the local hero known as Sheed suddenly emerged and began to sign for the crowd.

“When it was my turn, I said, ‘Ball don’t lie, Sheed!’” Crawley recalled. “His eyes flicked up, he got that Rasheed Wallace smirk on his face, and just said, ‘No it don’t,’ and grabbed the book and signed it. That made my whole year. It’s one of my all-time favorite sports moments.”

Crawley fondly described attending “so many” Pistons home games from that era when Wallace’s signature words all but echoed off Palace walls. “You could be in the upper bowl and still hear him shout it on his way to the bench,” Crawley told me. “He was very boisterous when he would go about saying it.”

But for all of his demonstrativeness, even Wallace doesn’t pretend that he invented the idea of “Ball don’t lie” altogether.

“I’m from the city of Philly,” Wallace explained a couple of years ago, in a short video for the All the Smoke podcast. “Just shit-talking in the street. Growing up, you hear different little things. Same phrase like you hear when you go to the hole and get fouled, you say what? ‘And one!’

“That’s all it is. Just street talking.”

When Matt de la Peña was working on his debut book around 2003, he was having trouble coming up with a title that represented the story as more than just about streetball. “Sometimes novels get marginalized when they’re sports-forward, so I wanted to highlight the other elements of the book [in the title],” he said. “But my publisher said it should suggest basketball, so I tried like 50 different ones, and I ended up going back to this line I’d heard growing up.”

De la Peña first encountered "Ball don't lie" as a college student in the mid-’90s while playing pickup over summer break at San Diego’s Municipal Gymnasium. “Rasheed said it when someone missed a free throw after a bad call,” de la Peña said. “Where I heard it was: Somebody makes a call, and then they mess up after, like a turnover, or a missed shot, and then someone would yell out, ‘Ball don’t lie!’”

After his book Ball Don’t Lie was released in 2005, telling a coming-of-age story of a teenage boy’s intersecting struggles in life and successes as a hooper, de la Peña discovered that not everyone who picked up a copy understood the reference on the cover. “I visited a lot of high schools when the book was really new, and I’d go places where everyone would grin when they saw the title,” de la Peña said. “It was almost an insider language, like, We know what this is.

“And then general readership would call it things like ‘Balls Don’t Lie,’ or ‘Ball Doesn’t Lie.’”

Wallace continued to indirectly provide lots of free publicity: A Free Press article from March 2007 estimated that the Pistons player had “probably said his catchphrase, ‘Ball don’t lie,’ after an opponent missed a free throw more than one-hundred times over the previous two seasons.” Still, there were indications that the bit was wearing thin, especially with officials. That same month, Wallace received what appears to be his first documented technical foul for hollering it.

“I said what I say all the time, with the, ‘Ball don’t lie,’ what I’ve been saying all year,” Wallace protested to reporters after the game, per the Free Press. “Bob [Delaney] thought when I said that I was directing it toward one of his partners out there on the officiating crew, which was not true.”

Whereas refs saw Wallace’s use of “Ball don’t lie” as directly antagonizing, others embraced its indirect significance. Brin Hill was one of the latter. A former Division III player at Vassar College who grew up hearing the phrase during pickup games back home in Los Angeles, the filmmaker found himself drawn to de la Peña’s book, eventually collaborating with the author on the screenplay for the 2008 film, in part because of what the title represents.

“In a world where everyone’s feeding you narratives and has got some bullshit story about how they almost went to Boston College, there’s a truth that basketball emits,” Hill said. “There’s no way to hide when there’s only 10 people on the court. There’s no way to lie. The ball’s always going to expose the truth about you. It’s the idea that this is the gavel of basketball.”

Hailing from the Detroit area, Justin Catchens was in high school when Wallace was traded in 2004 and promptly helped the team claim its first ring since the Bad Boys era. A lifelong Pistons fan, Catchens chanted “Ball don’t lie” in the stands of varsity games, yelled it on the court during rec league games, and even broke it out on the playground with no refs in sight.

“I think it’s a fun way to hint at there being some kind of balancing force,” said Catchens, now a New York-based comedian and actor who co-hosts the NBA podcast 89 Cavs. “It’s like the ball is this impartial arbiter, it will balance the game. ‘You called a soft foul—that’s why you missed that shot.’”

In 2017, an article from The Ringer looked through a small sample of NBA officiating reports for incorrect calls and subsequent scoring opportunities, ambiguously determining that “arguments for and against the ball lying can be made.” Eight years earlier, a paper in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology found that individual and league-wide free-throw rates were both “notably lower” than average following “obviously incorrect calls” over 102 NBA games during the 2007-08 season.

The ball seemed to be telling the truth.

But the legacy of “Ball don’t lie” can’t be measured in numbers. Rather, it’s about the “Ball don’t lie” hoodie that Catchens owns, gifted to him by a college roommate several years back, featuring Wallace’s face on the front. It’s about the urgent phone call that Crawley once received from an old friend, describing a work situation where a colleague had questioned the data in a spreadsheet that the friend had made: “He said that he showed his colleague the formulas that he used, that it was bulletproof, and he told them, ‘Ball don’t lie,’” Crawley said. “He had to reach out to me to tell me that.”

While it's not unique to basketball, no meme lives forever. LiAngelo Ball's song might be everywhere one day and gone the next. But the great ones stave off the inevitable descent from funny to trite and remain relatively present, albeit at a duller decibel level. "Ball don't lie" might not find another avatar quite like Sheed, yet it'll always have a spot in the game.

“I probably go to maybe four Pistons games a year these days, on average, and it’s a guarantee you’ll hear it from both fans and players,” Crawley said. “Especially fans.”

For his part, the author of Ball Don’t Lie felt that the phrase has “entered the cliché zone,” at least on the court. “Pre-Rasheed, you heard it so rarely that it had a little bit more of an esoteric energy,” de la Peña said. “Now I think kids coming up know it and hear it, so they repeat it without going beneath the surface.”

Even if "Ball don't lie" might be well-worn at this point, its impact cannot be denied. Seander, who released the song, also owns two federal trademarks for “Ball don’t lie,” one covering “non-downloadable video podcasts in the fields of sports and lifestyles,” and the other for clothing sold on his website and at concerts. Additional corporate entities with “Ball don’t lie” in their names have also formed in at least 12 states nationwide over the past two decades, according to public records, including the currently active Ball Don’t Lie, LLC of Michigan; Ball Don’t Lie, Inc., of Delaware; and a Ball Don’t Lie, domestic nonprofit registered in Ohio.

Overseas, the Ball Don’t Lie Australia podcast delivers hoops news to its listeners Down Under, while the Ball don’t Lie podcast—distinguished by the lowercase D—does the same in Italy. An old reporting source in China tells me that basketball-focused influencers there often write the characters for “lánqiú bù shuōhuǎng” in the headlines and captions of their posts on Douyin, the country’s version of TikTok, to demonstrate their dedication to the game.

“The main age group of NBA audience in China is around 35,” the source explained in a message, “and I bet most of us know it because of Rasheed Wallace.”

Asked about the legacy of “Ball don’t lie” in a 2018 Complex interview, Wallace hinted at a certain frustration over its proliferation. “I kinda feel like Bobby McFerrin, the mastermind behind ‘Don’t Worry, Be Happy,’” Wallace said. “I read in an interview somewhere that he hates that song because everybody’s always saying it to him.”

But it’s clear that the line came to take on greater personal significance for Wallace over time too. “If I’m doing a lot of hard work, in the gym, in the weight room, I’m putting that work in—then throughout your career, that ball is not going to lie,” he told the Philadelphia Inquirer for a 2020 article on his career transition to coaching high school basketball. “It can mean many things.”

Taken at face value, “Ball don’t lie” means that Ball always tells the truth. But what does that say about Ball? Is it capable of untruths, yet chooses not to tell them? Furthermore, what gives Ball this authority in the first place? Is it a tool of an almighty power, or does it possess the ability to adjudicate on right and wrong?

“The sport has so much history, so many people who came before—I wouldn’t say it’s almost religious, but people worship basketball,” said Harris, who entered the NBA in 2014. “So I understand when people talk about the basketball gods. It’s the law of basketball. They can’t lie.”

Pausing for a beat, he smiled.

“Plus, it’s fun to say.”