ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia — There’s a dramatic version of this story where I could make myself sound much cooler, but I’m a very boring man and so my hands are tied: I went to Ethiopia because I wanted to go to church. That’s not a normal thing to do, I’m told, but I had promised a friend from the Caribbean that I’d help him make a pilgrimage and I thought it would be pretty neat. I was baptized Methodist before I had much of a choice in the matter and I’ve always wanted to have two Christmases anyway. What better way to celebrate the Lamb than in Lalibela with my new pals, Rastafari and Ethiopian Orthodox alike.

I flew to Ethiopia on a commercial airliner, for fun (and lest the reader believe it is difficult for professional reporters to make contact with Ethiopian people, I had excellent data coverage). I was aware of the war because American newspapers mention it once every three to five months. The itinerary was to avoid the Somali region because petroleum politics have created forever war in the Ogaden, but I wasn’t going to avoid Amhara, and there’s fighting there, too.

“Aww, poor baby,” a young woman said, passing a stray dog near Mexico Square in Addis Ababa. “We have so many stray dogs here. But, you’re not one of those white people who only cares about the dogs, are you? The white women when they visit, if you bring up the dogs, it’s ‘Ooohhh my gawwsshhh’ the rest of the day.”

Stray dogs could work as a metaphor, but Western writers have a bad habit of dehumanizing people in places like this. Still, it’s tempting because it’s safer to write about the dogs. People can get hurt if one reveals too much about their experiences in Ethiopia. I'm not even going to describe in vague terms the speakers of most of the quotes in this story. It’s an open country, so the information is out there, albeit not in mainstream Western media sources. I’m also not qualified to cover it. I’m a religious history obsessive, not a war reporter. My skepticism of “parachute journalism” is hardwired—from growing up in America, I suspect, where everybody is always trying to extract something from you for money. But there are people paid to do this who aren’t writing about it and every day I wake up and wonder why. Objectively speaking, the Horn of Africa is a proxy war. Objectively speaking, if I report about which countries the Ethiopian people think are involved in nudging along the violence, I would be reporting subjective information as fact. It’s all very squishy, and one is not allowed to objectively point out that it all sounds eerily similar to stuff that happens when headlines like this are in the news.

Stray dogs get rarer as one travels north, where there is allegedly peace but famine and soldiers haunt the countryside. Children are not eating in Tigray, or Gondar, or Aksum, or Lalibela, according to reports by human rights organizations. It says something about media choices and coverage that most Americans I spoke with before my two most recent trips were more concerned for my safety in Jamaica than in Ethiopia.

This story was pitched as a piece of media criticism so that I could sell it to Defector. There are only about three or four publications left in America that will even take on stories from countries where people go to jail for writing about stuff they see. I don’t have the kind of background or connections to sell stories to those places. Even if I did, there’s only so much column space, and these publications need to optimize that space for advertisers and audience. Stories about Ethiopia don’t tend to make the cut, from what I can see.

Last year, I came back from a trip to Kingston with what I felt was an inspiring story about how, in many parts of the Caribbean, reparations for kidnapped Africans are still an imperative rather than being treated as an aspirational sideshow, as they are in the United States. An editor at one of the only major news magazines with the resources to cover this kind of thing let me know that they didn’t have the space for it, and since reparations didn’t seem politically feasible, there wasn’t really a point. If that’s not the kind of thing a random editor with a liberal arts degree should be deciding, well, that’s how the industry works. Staffers could jump on it, presumably, but staffers are reliant on where the money is directed. If management doesn’t want Horn of Africa stories, the Africa desk may suffer some budget cuts. This is all my assumption, though, because there’s not a lot of media reporting on the lack of media coverage of a war that has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. Meanwhile, if you’re well-read, I presume you’ve heard all about the podcaster from Stanford with lots of girlfriends and questionable wellness advice.

I understand why this happens. The first draft of this essay had a lengthy (and yet succinct relative to the complexity of the real world) explanation of the socio-political and ethno-religious history informing the modern civil war. I had a Tigrayan person from the Ethiopian diaspora give it a “sensitivity read” so that I knew I wasn’t too far out over my skis. She said that I nailed it! Unfortunately, almost none of it is in here! My editor pointed out that it would be impenetrable to the average reader. I need to meet American readers where they are, and can’t just go thrusting them headfirst into the skein of issues that arise when one of the oldest cultures on Earth tries to create a constitutional government. So I see myself tasked with explaining the delta between what’s in the news and what I’ve experienced, but in a way that also reflects the entrypoint of the layman.

Based on my experience over the last two years, the best starting place for the average American layperson is to tell them that Ethiopia is in Africa. One might be surprised how often people don’t know this, but they’ll say “Middle East” and, phew, that’s its own thing that is also complicated. Ethiopia has a complex relationship with colonization and the Scramble for Africa and abolitionist movements in the West. It’s never been colonized, which is a massive point of nationalist pride that some academics dispute due to the fact that, much like Liberia, Ethiopia’s economy was heavily dependent on Western markets. However, the indigenous languages of Ethiopia are still present and the Ge’ez writing system was used in the composition of some of the oldest Christian gospels. Amharic is the spoken language. “Never been colonized” means, among other things, that the dominant languages spoken in Ethiopia are local in origin rather than Indo-European. As an American, I’ve never thought about picking up a gun over a language, but that’s quite literally happening right now in certain areas of Ethiopia.

“I hate French. If I hear an African speaking French, it makes me want to vomit. English is fun but very weird.”

And then there’s Eritrea. One can’t understand the modern civil war in Ethiopia without a good background on Eritrea. But if one has no background on Eritrea, then the shorthand necessary to make any explanation of any of this fit the allocated space is only for fancier places. Those types of articles are on the websites that feel like the inside of a luxury automobile and I write for places that make podcasts. This Very Serious Story about a Very Serious Situation is probably running next to a 400-word blog about a Stephen A. Smith clip.

Would you like to hear about the Rastafari people? I’m told they are interesting when the topic comes up in conversation, but then I find out that people think Rastafari is just a weed religion. It’s an extremely complex esoteric tradition that is an extension of liberation movements from the Caribbean. There’s a spotty socio-political track record within its history and a very active issue in the movement’s present, as the younger generations of Rasta and ex-Rasta (comparable to American ex-vangelicals) begin their own liberation from orthodoxy. In the 1970s, some guys from Rolling Stone went down to Jamaica and wrote about how cool it was to smoke weed and stay up past their bedtime with Bob Marley instead of writing about how Bob Marley’s friends were getting tortured by state authorities for wearing dreadlocks.

The Rastafari people and their struggle in the Caribbean are directly related to modern Ethiopia’s divisions. I visited a place called Shashamane, a dwindling community of Rastafari who repatriated after the movement’s savior, the final Emperor of Ethiopia Haile Selassie I (his birth name and title was Ras Tafari Makonnen) gave 500 hectares of land to Westerners of African descent who wanted to return to the continent. Given the state of identity politics in modern America, a reader can maybe see why this was both an extremely powerful gesture and also a cultural powder keg. Much of Rastafari culture in the academic world is focused on advancing material conditions for the diaspora, but the media focus is often on the movement’s regressive Anabaptist social politics or the aforementioned commercial version of its philosophy. Rather than strictly a “new religion,” it’s a restoration movement of the same Orthodox Christianity that I experienced in Lalibela, albeit with a bit of extra stuff that the orthodox in Ethiopia don’t quite align on (Haile Selassie is not God in the Church, for example, because of Jesus, who readers might be familiar with but is different in appearance and interpretation in Ethiopia). I saw a Rasta ascetic at this big outdoor Genna festivity—Genna is Ethiopian Orthodox Christmas, celebrated on January 7—wearing cardboard with Revelation verses on it, and orthodox were cool about it. Some of the folks I met were pretty confused about why the Rasta don’t just adopt Ethiopian orthodoxy now that they moved there, but that’s not really any of my business. It’s a religion and you’re allowed to believe whatever the hell you want. Some people here in America get married with Chester Cheetah officiating. That’s none of my business, either.

What the layperson probably needs to know about Shashamane is that the Rasta who settled there are running out of money and there hasn’t been much repatriation among younger generations. The Rastafari and the Church tend to get into conflicts with the Oromo Liberation Front, a militia that is not fond of Haile Selassie and the Amhara aristocracy he represented, or the Church. The ethno-religious stuff is messy enough with the Christians, and I haven’t even mentioned Islam yet, which has its own complicated history in regions of the country with high concentrations of the Oromo ethnicity. There is still a hotly contested ethnolinguistic battle over the Amharic language – which is closely related to the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Church – in kingdoms that, prior to the 19th century, were predominantly Islamic sultanates. For some, the issue is the Oromo indigenous language and others the Arabic language; a fight for indigenous expression in the Horn or a fight for the language of Mecca over the language of Amhara.

“There was a Protestant who did a TikTok dance at an Orthodox Church. People wanted to find them and kill them. Bro. You don’t do that here.”

Addis was safe enough, and Hawassa was as beautiful as I’d read in the history books (if one were to go—which I guess I shouldn’t recommend one do—get the fish both fried and grilled at one of the myriad fish spots by the lake, with the hot sauce, some of which I allegedly smuggled home). Things aren’t great anywhere, based on how often I would ask a person with a car, “Can you take me to [cool place]?” and they would look at me like I was insane and then explain that it would not be good for me if certain people saw me in a car with them. Say no more, my friend.

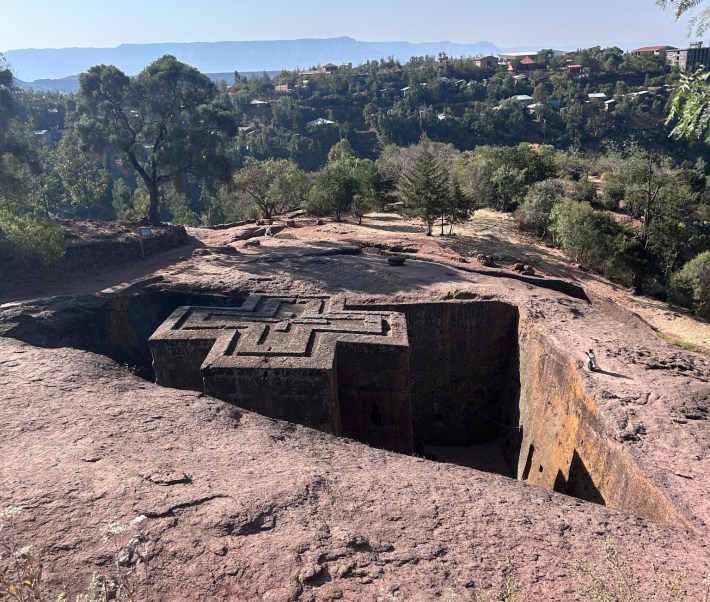

After I got there I understood why so many in the diaspora I talked to before visiting asked me if I was sure that I wanted to do this. (“Hell yeah, they don’t have rock-hewn churches over here in Pittsburgh, brother!”) There were more guns in Lalibela than I was expecting. Otherwise it was sick. I took holy water communion, got blessed by the Lalibela cross, and all of this stuff really meant a lot to me in a way that I can’t write because it’s a secular audience. I want to be earnest, but faith is personal and Defector’s editors and readers are strangers. I will volunteer that going to a church service in an active conflict zone does tend to add some weight to the eschatological stuff.

I also can’t write much about the militias in Ethiopia, unfortunately, because there’s no way for me to explain them without also linking the militias back to their ethno-religious struggle. Much of that struggle involves Christian history, both ancient and more recent with evangelicalism. I could tell you about how, right now, Ethiopia is essentially in the midst of its own version of Reaganism, but that would involve telling you how Pentecostalism even got there in the first place. It’s a long story. So is the illustrative stuff about the way Ethiopia is still struggling to convert from a rural, agrarian society ruled by Abrahamic laws; the metaphor I might spin up is about how Ethiopia, like America, is unavoidably burdened with the legacy of its founding fathers and patriarchal misogyny. Statues are covered in tarp. People are at each other’s throats over linguistic differences and ethnic terminology. Indigenous people still have almost no say compared to the monotheistic institutions. They even strongly dislike Catholics! It’s a little like Utah (with better art and food, in this author’s opinion, but that again is subjective).

I’d love to tell you everything I saw in Ethiopia but I can’t. It’s reportedly not safe to be very specific about stuff, and writing something that dances around the subject isn’t worth my or your time. Amharic speakers have a view into the conflict that Westerners don’t, since the real information is not in English. The extent to which anything even exists in English is for us, the audience that doesn’t speak the language of the place being pillaged. Speaking of pillaging, there’s this really amazing 12th-century church in Lalibela called Bete Giyorgis where one wall is blank because the Italians who invaded scrubbed it and were going to replace it with their own mural but then they got driven into the sea before they could finish.

There was a kitten there and the kitten hangs out with the monks, who sleep in a carved rock domicile with a small offshoot for drumming and praying. The monks are only allowed to eat this dark brown version of injera that’s a bit more sour and chewier. I tried some in Addis Ababa from an old woman who thought my tattoos were very nice, but said so in a way where I could tell she was really unhappy that I had tattoos. Whenever a kid would walk up to me and point at my funny colored skin they would say “Europe?” and then I would say “No, I’m American” and the kid would visibly perk up. That felt nice. I visited Switzerland last year and when people found out I was American they treated me like they’d found out I had cancer.

The stuff that’s printed in English is a lot nicer to the West than the stuff that isn’t. For example, I met some kids from Rwanda who had put together a skatepark for the community and the Rwandan government destroyed it to make a golf course. Reportedly the kids who used the skatepark now can’t afford to use the golf course, and the golf course is only used by businesspeople and visiting diplomat types. The New York Times had the populist angle nailed: “In Rwanda, an 18-Hole Sign of Growth.”

I got to watch a guy behead a live lamb on the morning of Christmas, butcher it for us, and then we sat and we ate the freshest meat I’ve ever tasted, and we talked about the Almighty, and we talked about Tekle Haymanot, and we talked about all the things we love about being alive. Mealtime in Ethiopia is when you learn about each other. Nobody has a plate, nobody has their own setting, everyone eats together from the same pile of injera, and nobody seems interested in making you feel like your existence is an imposition on their day. A friend bought me a comb with Saint George painted on it in traditional style and I explained that it was a kind gesture, but if I used the comb in America people would think I was being funny; it looked more or less like an afro pick. My friend was genuinely bewildered that Americans had racialized a comb. Buddy, you don’t know the half of it.

If it’s not clear, I’m white. The folks in Ethiopia could tell I wasn’t from around there. I’m not going to repeat stuff I was told ad nauseam because who knows? Maybe I only got some of the story, or a false story, and I don’t want to do the thing where a Westerner pretends he understands a foreign country just to impress other Americans who think of geopolitics through the lens of team sports. I can trust what I saw, though. I saw a lot of beautiful celebrations of Genna with a distinctive tone of defiance. I saw people decorating the streets for the Epiphany (or Timkat) with prayer flags, even though the federal government issued a warning that doing so would have consequences. I saw a lot of police in Meskel Square that night in armored trucks and riot gear as Tewahedo hung the prayer flags anyway.

I saw all the stuff that I’ve been reading had happened in Ethiopia under Haile Selassie that made him an evil autocrat, except now it was happening under a guy that isn’t an emperor. Sure, the guy in charge now is allegedly drone-striking his own civilians, but there was a vote first. Does that make it better? I met people in Lalibela who said they didn’t have a library anymore because it got blown up.

Anyway, I was there for church stuff. As a person of faith, I accept that any description I attempt of the power that exists within the rock-hewn walls of Lalibela’s churches will be inadequate. There are lots of wonderful travel blogs where one can learn the intricate details of the churches, the icons, the development of Aksumite and Zagwe and Solomonic versions of the Ethiopian faith. There are even reviews of Lalibela on TripAdvisor.com where one can read various Americans complain that $50 is too expensive to see a monument to immortality and the source of their entire faith system. Reading these reviews reminds me that my experience in Ethiopia was only as special as I wanted to make it.

Guenete Leul Palace is one of the only places in Addis Ababa where Haile Selassie is still unavoidably centered. In one of the palace’s rooms, there is an exhibit to the Rastafari people—one that features Mortimo Planno, the first Jamaican pilgrim to Ethiopia, rather than the tourist-friendly version in the West that centers Bob Marley. The desk where the emperor signed documents expelling the Italian fascists sits idly by a window with yellowing glass across from a massive portrait of the emperor in scholarly robes. Outside of the palace is a monument built by the Italians during their occupation: a circular staircase to the heavens with a new step for each year of fascist rule. Never one to waste good craftsmanship, Haile Selassie did not remove the monument when he seized his palace. Instead, he had Ethiopian artisans craft an addition to the top of the monument: the Lion of Judah lays atop the last step built by the fascists, gazing out over the courtyard at the next generation of Ethiopian scholars. Tourists can find any number of students outside the Palace ready to practice their English with Ferenji who come to see the museum.

“You study propaganda?”

“Yes.”

“Perhaps you will write some propaganda for us when you get home.”

“We aren’t allowed to do that in America. I’m only allowed to write down what happens.”

“Do you think that will be enough?”