This article was originally published on Hell Gate. If you like it, we encourage you to visit their site and subscribe.

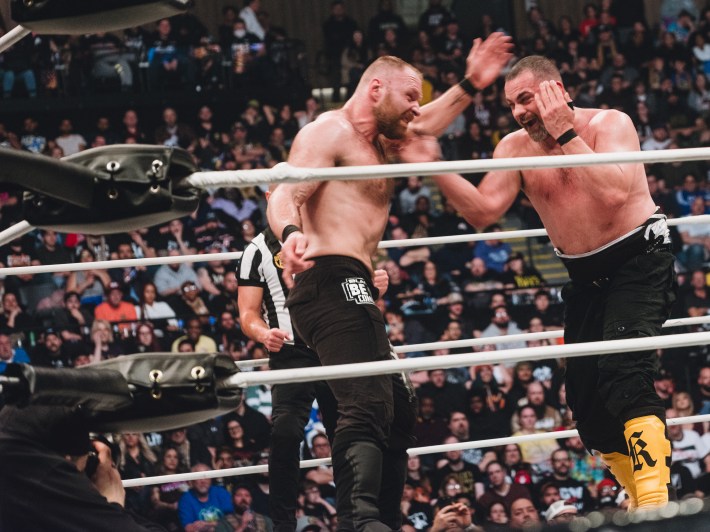

The pro wrestler Eddie Kingston pushed his opponent, Jon Moxley, into the corner of the ring at Nassau Coliseum in late December and posed a question: "You want 100 percent, mothafuckah?" It was rhetorical. Kingston, drenched in sweat and with a scowl on his face, reared back and slapped his right hand across Moxley's chest three times in succession, with such force the sound echoed through the arena packed with 10,000 screaming fans. Soon, the crowd was chanting his name:

"Edd-ie! Edd-ie! Edd-ie!"

Sitting in the front row, Daniel Acevedo, 17, recorded a video on his phone as he cheered on his favorite wrestler. "C'mon Eddie! Do it for New York!" Acevedo yelled. "Do it for Yonkers! Do it for chopped cheese!"

The 42-year-old Kingston (his legal name is Edward Moore) isn't your average pro wrestler. A Bronx native who grew up in Yonkers, he talks trash with the attitude of a quintessential blue-collar New Yorker ("I'll knock ya jaw right off ya face, pahtnah," he once said to an opponent), with a blend of passion and intensity that seems to blur the lines between fiction and reality, but is equally as frank in discussing his mental health and his struggles with depression. A Yankees hat often sits atop his buzzed head, and he likes to wear hoodies and baggy sweatpants over his 6-foot-1, 244-pound frame. He has two slits in his right eyebrow, a gravelly voice, and the urgency in his gait of someone who has places to be.

He's also, after nearly two decades of toiling on wrestling's gritty independent scene, one of the most beloved performers in All Elite Wrestling (AEW), which is owned by billionaire Tony Khan and, since its founding in 2019, has quickly become the main competitor to the global juggernaut World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE).

"Eddie Kingston is an extension of me at 17 years old," he told me in advance of his match against Moxley. "I was an angry kid, you know what I mean? Who hated people but also hated himself. And because of that, I didn't know how to handle that or speak about it. So it came out in violence."

That temper led him to "so many holding cells it would make your head spin," he wrote in a 2021 Players' Tribune piece. He spent his teen years throwing punches in street fights and running from the cops. But when he sat down to watch wrestling, it was like all that rage went away; the ring became his sanctuary.

In 2023, Kingston channeled his aggression to reach new heights in his career, winning New Japan Pro Wrestling's Strong Openweight Championship, and then claiming the Ring of Honor World Championship, the highest prize in AEW's developmental brand.

But for Kingston, the fame is almost beside the point. When Kingston is in the ring, his mind goes blank. He feels free. The very real anger that has shadowed his entire life finds a home.

Kingston was born to an Irish father and a Puerto Rican mother, and spent the first 10 years of his life in the Bronx before moving to Yonkers. In his telling, he was bullied at school because he was mixed-race, and he picked up the mean streak wrestling fans would later fall in love with from the men on the Irish side of the family.

In his grandfather's home, a wooden sign summed up the family's philosophy: "Take me or love me, or leave me the fuck alone."

He found that same spirit in the professional wrestlers he watched on VHS tapes—especially Japanese wrestling, which prioritized physicality and hand-to-hand combat more than the character-based WWE. By his early 20s, after graduating from the Chikara Wrestle Factory in 2002, Kingston was working on the independent scene, wearing pants emblazoned with a Puerto Rican flag and being introduced as from the "tough streets of New York." But the same raw anger he displayed in the ring, turning his opponents' chests red with his blistering open-hand smacks, got him into trouble.

"Not going to the gym. Showing up late to shows. Not going to shows because I was in the drunk tank. Fighting with promoters. Fighting with other guys in the locker room," Kingston said, describing his early days in the business. "I also still had one foot in the streets, doing street stuff and then trying to also do pro wrestling."

He found a mentor in Homicide (real name Nelson Erazo), another New Yorker working the independent scene who was four years older than him. "Eddie was gang-banging, doing stuff that I used to do," Homicide recalled. "I told him, 'Hey man, you got so much talent. Do something with your life.'"

Kingston continued to struggle with alcohol and pills, and considered suicide. One day he found himself sitting at a pond holding a knife, when his phone rang. It was Homicide.

"I can't remember exactly what I was saying," Homicide said. "It was a lot of f-bombs. Like, 'What’s wrong with you?'"

That call, Kingston said, saved his life. "I think about Homicide any time I'm at any arena, because without him, I wouldn't be here," he said.

Seeking a fresh start, Kingston moved to Orlando. And he kept fighting.

Kingston soon became a popular figure in the sport's scrappy indie scene, wrestling for smaller companies in bingo halls and high school gyms across the country, but nearly 20 years into his career, he hadn't reached the global stardom of some of his former peers, like multi-WWE Champion Bryan Danielson. When the pandemic hit, Kingston was unable to work and was prepared to sell his Orlando home and move back in with his parents in Yonkers.

And then, in July 2020, Kingston got an opportunity. Cody Rhodes, a former AEW performer and executive vice president, who now wrestles for WWE, saw a promo Kingston had cut on the indie scene and wanted to bring him in to wrestle him on TV.

"You know what I grew up around? Alcoholics! Junkies! I grew up around that! And I had to survive! I had to grind!" Kingston said to Rhodes before the match, his face turning red and his voice rising. That intensity carried over to the match, during which Kingston power-bombed Rhodes onto a smattering of thumbtacks he had strewn across the ring in what would turn into a losing effort. Viewers watching at home were enthralled. Soon, #SignEddieKingston was trending on Twitter.

Khan signed him a week later. Kingston became one of AEW's featured acts, and in on-screen interviews, commonly referred to as "promos," he won over fans with his passion but also his vulnerability: He spoke about his troubled past and his anger issues, his mental health and his Zoloft prescription.

Those real-life demons, as well as Kingston's winding journey to AEW, have been incorporated into his character's storylines. In one promo battle, aired on Nov. 5, 2021, Kingston pointed his finger and scrunched his eyebrows as he addressed his nemesis, CM Punk.

"You," he said, with contempt in his voice, as he walked toward Punk, one of the wrestlers he shared locker rooms with on the independent scene. Punk, like Danielson, had gone on to become a WWE Champion several times over while Kingston's career floundered. "You judged me. I came to that locker room to get free. Free from my mental crap. Free from the streets. I came to that locker room for brotherhood, and all you did was judge me."

By the end of the segment, Kingston had flung off his beanie and his New York Knicks hoodie and attacked Punk, having to be restrained by AEW referees. It was all part of a planned segment meant to generate interest in a future match, but Kingston had channeled real emotion.

Signing with AEW (he earns six figures annually) didn't make Kingston’s problems go away. While promos offer him a medium to work through his past, they can also be triggering. He's developed a coping strategy to work through those moments: He leaves the arena and "meditates."

"The type of meditation I'm talking about, it's illegal in some states," Kingston quipped. (He likes to, as he told me, "smoke a lot of weed.") He added, "Wu-Tang likes to meditate the way I meditate."

It's a necessary intervention, he said, so he can be a "productive person in society."

"When I get into that mode, or that zone, I got to break it, or I'll be like that for days," Kingston said. "I worked very hard to not be that person anymore."

.@MadKing1981 is a mad man on the mic 😳 #AEWDynamite pic.twitter.com/qtfL17WwRz

— AEW on TV (@AEWonTV) July 23, 2020

But that outlook hasn't stopped him from embracing a new nickname, one that began as an insult. On Dec. 2, 2023, Kingston lost a hard-hitting match to Danielson, who signed with AEW in 2021. Danielson—with his ripped physique and gilded resume—represents the antithesis of Kingston within the world of wrestling, and after the match, he smirked as he pointed to a sign he had plucked from someone in the crowd: "EDDIE IS A BUM."

Kingston, who had long gone by the nickname "Mad King," decided to begin using a new moniker: "King of the Bums." And three-and-a-half weeks later, Kingston atoned for that loss by defeating Danielson, earning a spot in the finals of the Continental Classic tournament against his longtime friend Jon Moxley, to take place on Dec. 30 at Nassau Coliseum on Long Island, about 30 miles from where Kingston grew up.

That match ended when Kingston walloped Moxley with a spinning backfist to the face and pinned him for the win. As the arena erupted, Kingston was presented with the new Continental Classic championship belt, which was engraved with a crown. He raised the championship above his head, as if crowning himself—here, in front of all his subjects, stood the King of the Bums.

"I compare Eddie's character to the '90s Knicks," said the teenage Acevedo, a Queens native. "He's not going to give up without a fight. Like, he could be down and out, and this motherfucker is not going to give up." Acedevo added, "This motherfucker is from New York."

Hours before that show, Kingston had sat and watched as wrestlers nearly two decades his junior rehearsed their matches in the ring. "Do I feel like I relate with a lot of people here? No," he said. For all of his newfound success, Kingston still considers himself "one with the underdogs."

"I understand the lowest of the low, I get it, I've been there,” he said, describing why he took on the new nickname.

"So, why not? I’ll be the king."

This article was originally published on Hell Gate. If you like it, we encourage you to visit their site and subscribe.