Pollo del Mar wants to be hated. As a bad guy (or heel) in the NWA—the National Wrestling Alliance, a professional wrestling company owned and operated by the Smashing Pumpkins’ Billy Corgan (no shit!)—it’s her job to get heat, i.e. the boos and jeers and chants that separate professional wrestling’s villains from its heroes. There’s just one problem: She’s a drag queen, and it’s made her too popular.

“I would love to be a true heel in the world of professional wrestling,” says Paul Pratt, Pollo’s real-world alter ego. “But it’s ultra-challenging, because the moment I walk through the curtain, people erupt. They know that drag queens are supposed to be sassy and bitchy, so even when I say horrible things to people, they’re like ‘Yass, bitch, read me for filth! The library is open!’ It’s so frustrating. I just called you a piece of trash! You’re not supposed to like it!”

Such, in the main, is life in professional wrestling in 2023. When I got back into this strange American art form in 2018, three decades removed from my childhood fandom, I was stunned to see the representational progress that had been made. Women’s wrestling was treated seriously, not as an occasional afterthought or a bra-and-panties sideshow. Foreign wrestlers, like Japanese superstars Shinsuke Nakamura and Asuka, had their names pronounced properly (and, unlike ‘90s sumo-themed Samoan superstar Yokozuna, were actually Japanese). Black wrestlers win championships, without being shoehorned into stereotypical personae to find a place on the roster.

And largely gone from American wrestling are the gaybaiting gimmicks of yesteryear, when comical effeminacy or predatory overtones made characters like “Adorable” Adrian Adonis or Golddust into hated heels. (I have vivid memories of attending a non-televised WWF “house show” at the Nassau Coliseum as a kid, watching “The Genius” Lanny Poffo mince around the ring limp-wristed to rile up the crowd.) As with women and BIPOC, there’s still a ways to go, particularly with regards to the amount of television time they receive relative to the cishet white male performers who are still the norm for the art form. But queer wrestlers, who are out in increasing numbers, are now more likely to get cheered than booed—even when, in Pollo’s case, they’d prefer the opposite.

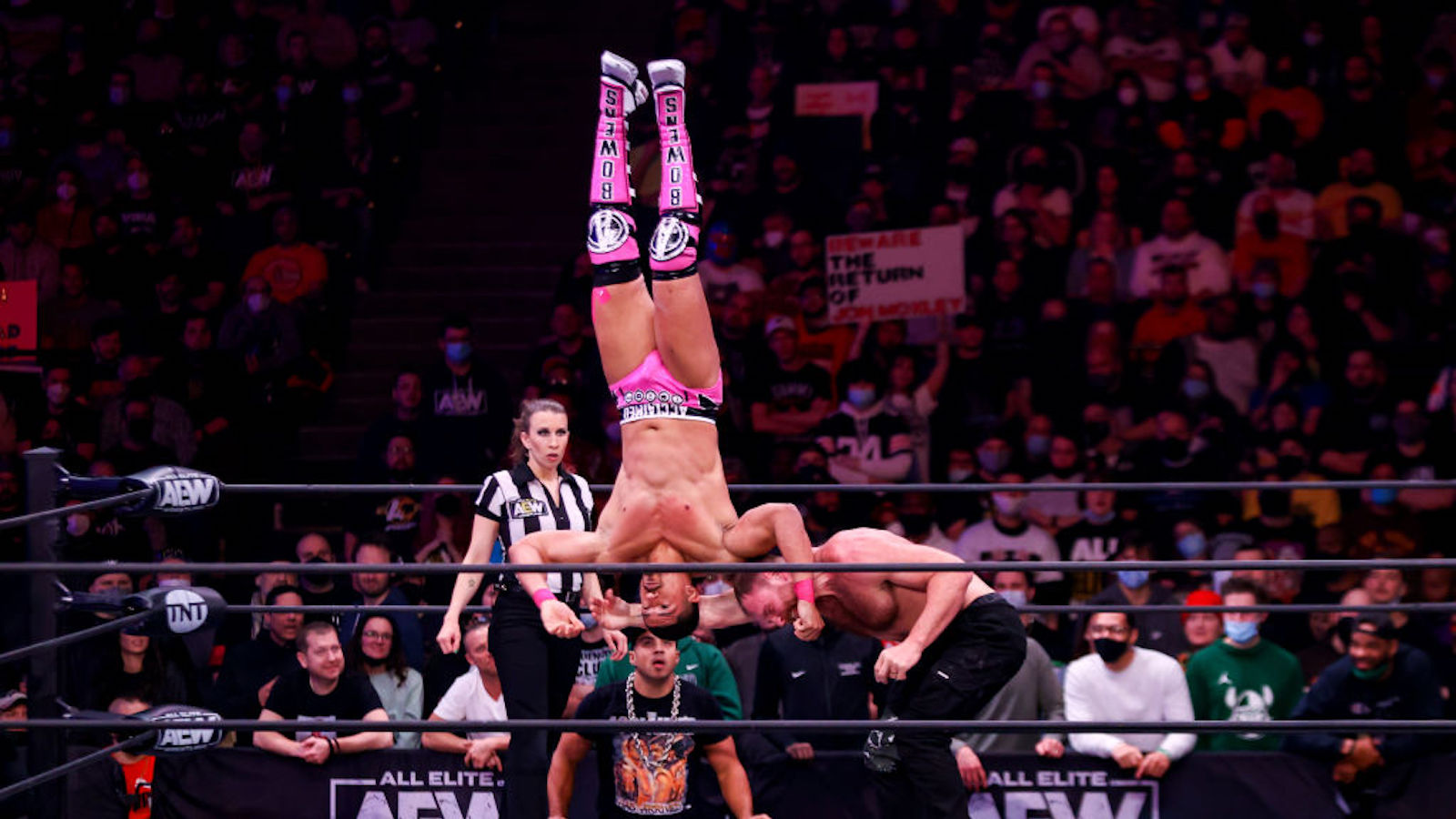

There’s no better demonstration of this phenomenon than the crowd reaction Anthony Bowens, one half of the former All Elite Wrestling tag-team champions The Acclaimed, received when he responded to sexy heel Harley Cameron’s crude come-ons by gesturing to the Pride colors on his trunks and saying, “I’m gay.” The crowd not only roared its approval, but chanted “HE’S GAY! HE’S GAY!”—inarguably the first time an arena full of wrestling fans have hollered these words and intended it as a positive.

“I never in a million years could have imagined something like that happening when I was younger,” Bowens says of the viral moment. “To say, ‘I’m gay’ on television and have a whole arena chanting ‘He’s gay’?” He laughs, seemingly in spite of himself. “Incredible.”

Nyla Rose may be the poster child for this brave new era of rasslin’. Trans, Black, and indigenous, she was AEW’s second-ever women’s world champion (after defeating inaugural champion Riho, who is Japanese). On the phone, I call her the most successful trans wrestler of all time. “I don’t know if that’s true,” she chuckles, “but I like the sound of it, yeah.” But for her, success lies less in achievements and accolades and more in being treated like anyone else in the locker room.

“To myself,” she says, “I’m just another wrestler, another person living their life doing their own thing. That’s the way I’ve been treated, nothing more, nothing less. As boring as this may sound, that’s very exciting for someone like myself. I’m living a normal life.” That’s not to say she’s unaware of the impact her existence, at this level, in this sport, could have. “It’s our job as the performers to continue to push those boundaries, show the world the possibilities, and maybe, in that course, change a few minds and hearts.”

But around the country, minds and hearts have shifted rightward, at least in governor’s mansions and state legislatures. Since roughly the 2020 midterms, in which Republican campaigns based on libeling trans people took an absolute shellacking, only for the party and its minions to double down on the issue, matters of LGBTQ+ acceptance and equality which once seemed settled have been in flux, to the community’s detriment. This drive to push back against the existence of queer people, especially those who do not conform to traditional gender binaries, has seen frightening levels of success considering the lack of public desire for such regulations, and it’s happening at a dizzying speed. (When my fellow New York Times contributors organized apparently successful efforts to change the tenor of the paper’s coverage of trans issues, events on the ground frequently unfolded faster than we could keep up.) On the last day of Pride Month, the preposterously corrupt Supreme Court issued a decision to legalize discrimination against queer people.

As a wrestling fan, I had begun to worry about the trans and genderqueer practitioners of the sport even before this. The art form’s two largest American promotions, WWE and AEW, are largely headquartered in Florida, reichsgau of the virulently queerphobic and racist Ron DeSantis, as is the prominent AEW-affiliated brand Ring of Honor. (AEW/ROH owners Shad and Tony Khan run things out of Jacksonville, home of their NFL team the Jaguars, while WWE’s Performance Center, a training and filming facility, is located in Orlando; consequently, many wrestlers make their home in the Sunshine State.) The storied wrestling brands Impact and NWA, meanwhile, are headquartered in Tennessee, another state at the vanguard of anti-trans and anti-drag legislation.

Pollo remembers the chain of events well. “I’m getting ready to do a pay-per-view event in Tampa, Florida. Everybody’s seeing each other for the first time in weeks, and it’s like a family reunion—everyone’s at the bar at the hotel, chit-chatting and having a good time. Then my phone vibrates, and somebody has sent me a news headline: Tennessee, where I get my checks from, has passed this anti-drag law.”

From the biggest companies to the smallest independent promotions, wrestling is a touring business. It requires performers to travel (often at their own expense) across the country, including to many officially anti-LGBTQ+ red states, for bookings at both wrestling shows and the lucrative convention and autograph circuits surrounding them. In the sport’s most high-profile incident of transphobia to date, WWE Hall of Famer Rick Steiner launched into an ugly transphobic harangue against Gisele Shaw, a trans woman who wrestles for Impact, at Los Angeles’s WrestleCon event in April. Steiner, whose legal name is Robert Rechsteiner and who serves as Vice Chairman of the Cherokee County Board of Education in Georgia, was expelled from the convention; WrestleCon promoters allowed him to be booked for their upcoming Detroit event, then disinvited him again after community outcry.

What hard decisions would the trans and gender-nonconforming performers I enjoy have to make about where and when to work? Or would those decisions be made for them by the bottom-line-minded companies they work for?

According to the wrestlers I spoke with, the verdict is mixed. For Sonny Kiss, the influential genderfluid trans femme wrestler who has worked for AEW (and subsequently ROH) since its inception, the shift is upsetting. “Almost a year ago, I changed my drivers license to ‘X’ for ‘non-binary.’ Now I’m like, ‘Hmmm. I think I should probably pick a side on my ID, because I’m scared that [the authorities] are gonna look at that and be like, ‘Ugghh.’ I try not to overwhelm myself, but it is definitely devastating to think that my rights could be taken away simply for existing.”

“One of my biggest fears,” says Kidd Bandit, an up-and-coming young wrestler on the independent circuit who began transitioning while she was already wrestling professionally, “has always been that a fan comes up, watches me do my show, I perform great, they do picture-takings and get autographs and buy merch, and then they find out I’m trans. Suddenly, they feel disgusted, because they’re a bigot. Did you not pay money to get entertained? What does it matter if I’m transgender if you got your money’s worth? That’s always been in the back of my mind.

“It’s always scary as a trans woman to perform in Republican states that are legalizing transphobia,” she continues. “You think you did a good job, only for fans to turn on you not because you didn’t wrestle well, but because of who you are as a person.” There’s an added burden to perform that comes with this prejudice, she says. “There’s a lot of pressure for myself and a lot of my trans peers to be at our best behavior at a time like this, because any misstep is going to be used not just against transgender people in wrestling, but transgender people as a whole.”

For Rose, a mother of two, the issue hits home in other ways. “To get a little personal, I wanted to take my family down to Florida for a Disney World trip,” she says. “Well, I can’t do that now. And unfortunately, my kids have to suffer, because they could be taken away from me. That is absolutely insane to say, but that’s the case.

“As far as myself on a personal level and traveling solo, I have to be hyper-aware. Is somebody looking to be vindictive, or to prove a point? There’s a heightened sense of paranoia. If there’s a convention held in a certain place, I’ve really got to weigh the options. Is it worth it for me to go someplace where I could literally be arrested for existing?”

According to Pollo, all of this has practical ramifications for the booking of wrestling shows. “The [NWA], I think, makes judicious decisions in relation to me. There are places I think that maybe the company would not necessarily include me on a show. But not every person is included on every show. So it’s a choice about where some people might be better off. They don’t want to create a shit storm for anyone.”

Pollo’s position is complicated by the fact that the NWA’s current world champion, Tyrus, is a transphobic right-wing media personality who frequently appears on Fox News. NWA owner Corgan, no stranger to right-wing ideology himself, has repeatedly defended his champion, telling the New York Post “I don’t believe in canceling out a voice because you’re not comfortable with their perspective.” (It seems safe to assume he’d prefer not to cancel out the NWA name appearing on the most-watched news network in America on an almost nightly basis, either.) Pollo, however, says she has not been affected by this rightward slant at the top. "My identity has never been seen as a negative, ever, in my dressing room, [in] almost three years with NWA.”

For their part, Bowens, Rose, and Kiss describe AEW as supportive as well, with Kiss noting that the company’s support for talent with marginalized identities also applied during the height of the Black Lives Matter movement: “They had an entire staff meeting about making us feel comfortable,” she notes. “With LGBTQ workers, they’ve basically always given us an opportunity to tell our own stories.”

In a statement issued to Defector on how anti-LGBTQ+ legislation has impacted the company’s use of queer talent, an AEW spokesperson said, “Professional wrestling is for everybody—in every state and every community—and our focus in all we do at AEW is to make that a reality. Making sure wrestling is for everybody means living a mission that includes taking our shows to as many fans throughout the U.S. and the world as possible, while supporting every member of our AEW team along the way.” WWE, NWA, and Impact did not respond to inquiries.

Kidd Bandit feels as though she’s identified the source of the problem: “The real enemy in this day and age are the rich and powerful,” she says. “They’ll incite discord among the lower classes so that people fight each other instead of fighting to climb out of the hole they stuck 99 percent of the population in. It’s rich people. I know it sounds like a conspiracy, and I hope I don’t sound crazy, but that’s what I believe.”

For Rose, educating her fellow wrestlers as to the stakes of the issue has been key. “These evil bastards know what they’re doing, and they know what they’re doing is wrong, so they’re skirting around the issue, hiding it behind certain language,” she says. “Not just my coworkers, but fans, regular people, aren’t fully aware of the impact this is having, because these new laws are worded in such a way that it’s easy to get caught up. Even myself: I’m like, ‘Wait, does this apply to me?’ So it’s no fault of their own. But the look of horror on my coworkers’ faces when I explain it to them, and the amount of love and support they give once they realize the gravity of the situation … they want to fight back.”

And to a person, the wrestlers I spoke with are optimistic about the future of their place in the profession, in large part because of the courageous and pioneering work done by their fellow queer performers. “It’s a relay race,” Pollo says. “One person does the best they can and goes as far as they can, and they hand the cause off to another person, and that person takes it a new distance. We might not ever get to the finish line ourselves, but we know that we helped lay the groundwork for it.”

“The generation after us is definitely gonna come in and continue to keep passing that torch and shoot queer wrestling to the moon,” Kiss says. “It’s a matter of time before we see more and more representation, because we’re all doing it our own way.”