If there's a baseball player who was ever the best at being the worst, it's Ray Oyler. Almost every one of his batting statistics from his six-year career that ran from 1965 to 1970 are horrendously anemic, even at a time when pitchers were the dominant force in the sport. His career-high season average was .207 in 1967, his only year above the Mendoza line. His OPS never even touched .560. Per OPS+ he was, at the absolute peak of his powers, 61 percent as good as the typical major-league hitter. His career average of .175 (with 15 home runs!) is the second-lowest in history by any position player with at least 1,000 at-bats, after the dead-ball era's Bill Bergen.

And yet despite a legendary incompetence at the plate, Oyler holds a special place in the history of not just one, but two baseball cities. As both a fan favorite on a failed expansion experiment in Seattle and a crucial character in the Detroit Tigers' 1968 World Series story, Oyler was so much more than a guy who swung a twig for a bat.

Oyler, who's listed on his 1968 Topps card as standing 5-foot-10 and weighing just 165 pounds, captained the baseball team and quarterbacked the football team as a high school kid in Indianapolis, then passed through the Marine Corps before being signed by a Tigers scout in 1960. In the minors, he managed to hit adequately for a shortstop, but he left an impression on everyone with his magic glove. Footage of him playing isn't easily available, and his metrics, while quite good, aren't unparalleled. But many of Oyler's contemporaries have attested to a kind of understated, consistent craftmanship in the way he played short. When he brought the 27-year-old Oyler up to the show in 1965, Tigers manager Charlie Dressen said, “Several scouts have told me he is the best fielding shortstop they’ve seen. Not our own, but Pittsburgh and New York scouts.”

But though his defensive talents carried over to the highest level, the hitting never improved like the Tigers hoped it would. In his first season in Detroit, Oyler slashed just .186/.265/.294 in 217 plate appearances. In 237 PAs the next year, he slumped to .171/.263/.252. Oyler reportedly tried anything he could to step up this side of his game, including changed stances, switch-hitting trials, and even wearing glasses. But none of it seemed to work.

Tigers pitcher Denny McLain once remarked that Oyler “couldn’t hit his way out of a room full of toilet paper with a crowbar. But the way he could field, I’d keep him on my club if he couldn’t hit his weight.”

Aside from a knack for the sac bunt, everything about Oyler's offense was a liability, and his reputation became such that by 1968 frustrated Tigers fans would sarcastically cheer his foul balls, because at least he had made contact. (“I hated to see them making fun of Ray," manager Mayo Smith said.) Though the Tigers dominated the AL in '68, Oyler's play only got worse as the year went on. After hitting .220 in the month of April, he dropped off to truly unacceptable levels, and he ended the year with a .135/.213/.186 line. As the team cruised to the pennant, the idea of Oyler having to step into the box against Bob Gibson of the NL champion St. Louis Cardinals felt more like a cruel joke than a viable lineup.

Detroit was not short on good hitting. The trouble was just where to put it all, particularly after right fielder Al Kaline returned from a broken arm he had suffered in May. In left field the Tigers had Willie Horton and his 36 home runs. In right they had Jim Northrup and his team-best 90 RBI. At center was Mickey Stanley, their best all-around athlete. And at first was Norm Cash, second on the Tigers in slugging. Seemingly every position the veteran Kaline could play was accounted for, so Mayo Smith gambled that raw talent could make up for inexperience, and in the final stretch of the regular season he moved Stanley to a brand-new position at shortstop while putting Northrup in center and sticking Kaline in right. Ray Oyler was demoted to late-game defensive replacement.

The Tigers' unorthodox fielding set-up dominated the chatter in the build to the World Series, but it turned out to be a genius call by Smith. Stanley answered all the questions asked of him, and Kaline, the man for whom this move was meant to accommodate, responded with a monster, career-defining series to cap off an uneven year. The Tigers lost three of the first four, and faced elimination with a 3-2 deficit in the seventh inning of Game 5, but a clutch Kaline single with the bases loaded pulled out the victory. In the next game he went 3-for-4 with four runs driven in. And in the deciding game, the Tigers earned their first championship since 1945. It might not have been possible without (or "with," depending on how you choose to look at it) Ray Oyler.

Oyler's benching was his swan song in Detroit. He was drafted by the most ill-fated of the four expansion teams entering MLB in 1969, the Seattle Pilots. This was a franchise in trouble from the start: paid for with borrowed money from former Cleveland owner Bill Daley, rushed into its first season because Kansas City was impatient to get the Royals up and running and the AL wanted an even number of teams, and stuck in the aptly named Sicks' Stadium while they waited in vain for what eventually became the Kingdome.

The Pilots lasted just one season before they ran out of money and were sold to Bud Selig, who turned them into the Brewers. But as a misfit player on a misfit team, their starting shortstop briefly found a kind of acceptance that had escaped him in Detroit.

It began with Pilots manager Joe Schultz's evaluation of Oyler's abilities. Asked at spring training about the concerns surrounding his shortstop's bat, Schultz responded, “Ah, hell. Ray Oyler will bat .300 for us with his glove.”

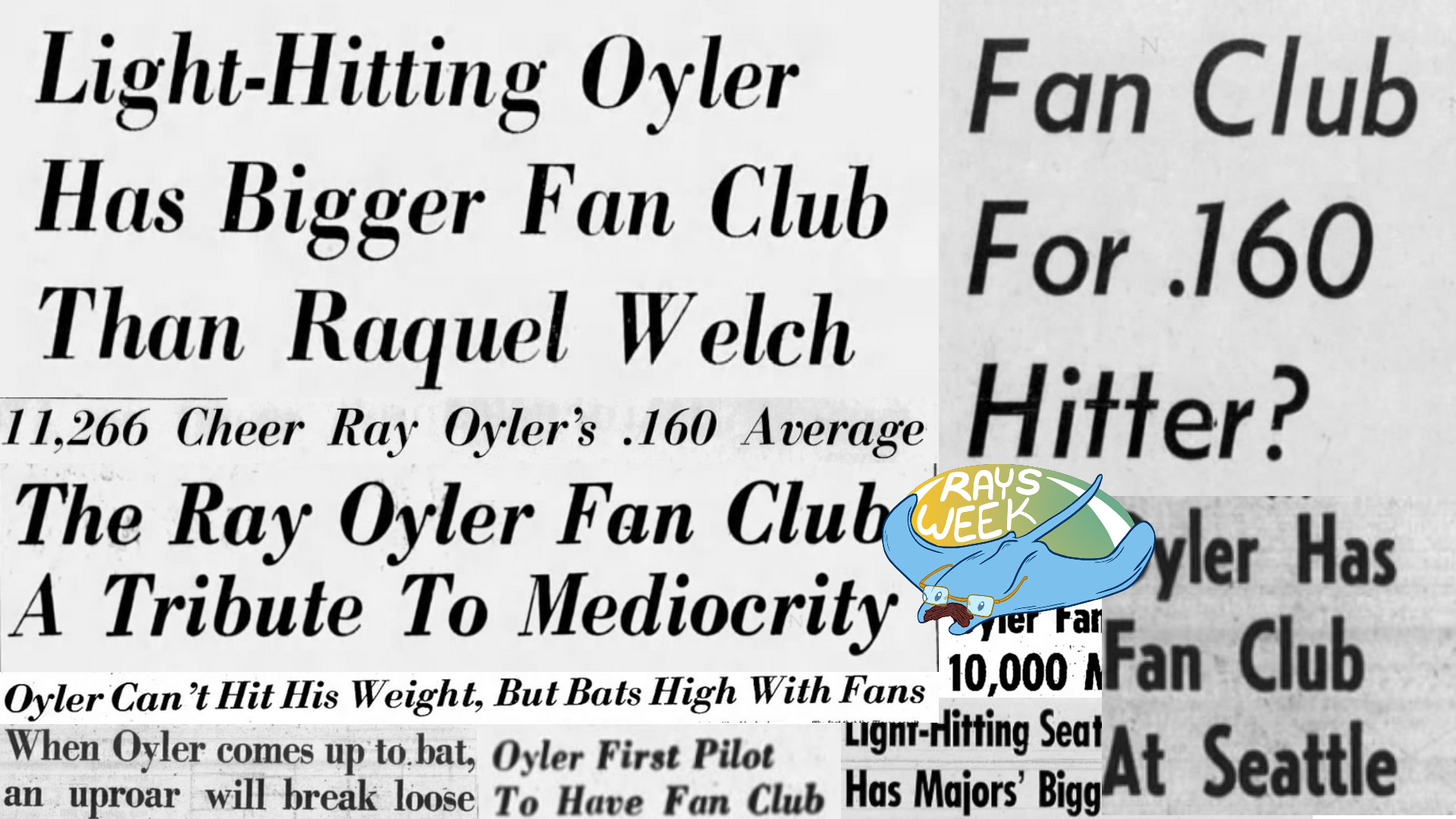

A passionate group of Seattle baseball fans, however, believed that metaphorically hitting .300 wasn't enough, and local DJ Bob Hardwick decided ahead of the season to start a Ray Oyler fan club. Playing off the catchphrase of the TV show Laugh-In, it was called the "S.O.C. I.T. T.O. M.E. .300" Club, or "Slugger Oyler Can, In Time, Top Our Manager's Estimate and hit .300." There were official membership cards and everything! The club wasn't just a tossed-off gag: Its members reportedly gave Oyler a car and a dog, vocally cheered for him at games with the "Sock It" rallying cry, and made him the clear-cut favorite player on a team of cast-offs.

Wrote Eric Whitehead, Vancouver columnist, "The Seattle fans, like fans anywhere, are hero-hungry, and in some strange fit of perversity they picked Oyler as their man."

Time Magazine claimed that 15,000 fans signed up for the club, or nearly twice as many people as the average attendance at a Pilots home game that year. “If you have to ask, you’ll never understand,” Hardwick said of why he singled out Oyler.

"Gee," Oyler told UPI ahead of Opening Day. "Nothing like this has ever happened to me before. But I'll be in there trying."

The fan club, at first, seemed to have a Midas touch, as Oyler started the '69 season hitting .350 in his first six games and even walloped a rare home run. Whitehead was quite concerned by this turn of events. If Oyler could hit a lick, would he still be lovable?

As one awed and pensive fan in the grandstand pews was heard to relate through a mouthful of hot-dog: “Oh, what a miracle is it here that we have wrought!”

A fair sort of soliloquy, forsooth.

A strange and wondrous thing has happened. Oyler, who really should know better, is plainly beginning to think he is as good a hitter as he is not supposed to be. He is drunk with the power of suggestion. He was picked as a folk-hero because of his classic ineptitude, because he couldn't hit a lick, and thus literally cried for love.

Now it looks as though the fellow might turn into a decent sort of hitter and wreck the whole humanitarian concept of the Ray Oyler Fan Club, which may soon be no more, Could be that the troubled members have created a monster, and when will we ever learn not to mess around with nature?

He needn't have worried. By the end of April, Oyler was back down to .220. By the end of May, his average was .190. After June: .176, and the floor kept dropping. But even while most of Seattle showed a plain disinterest in the woeful Pilots and their crummy ballpark, the Ray Oyler Fan Club stayed alive. When Oyler took a punch that gave him a black eye during a brawl with the Royals, Hardwick took it upon himself to send a telegram to Kansas City's GM demanding an apology and warning him that "Sock It To Ray Oyler" was not meant to be taken literally. ("Oyler Fan Club Mad Over Mouse" was the headline in the Kansas City Times.)

Fists aside, Oyler's local fame also made him a target for ribs from opposing dugouts.

"They'll holler something like, 'How in hell can a .160 hitter have 11,000 fans?' But I don't let 'em bother me with their yelling," Oyler said in August. "I always answer 'em the same way. 'Just lucky,' I tell 'em."

Unfortunately, neither the Pilots, the fan club, or even Oyler's career could survive far beyond this one bizarre year. Oyler was shuffled from Seattle to the A's to the Angels after the 1969 season, and he finished out his MLB run going 2-for-24 with California. He hung around the Pacific Coast League for a few years as a player-coach, but after retiring from baseball, he and his wife Joanne decided to make their home in the city that had made him feel welcome. The Oylers bought a house in Redmond, Wash., and Ray worked at Safeway and then Boeing. He played softball, pitched batting practice when the Tigers came to town, and raised two girls. In 1981, at just 43 years old, Ray Oyler died of a heart attack.

The near half-century of baseball that the Seattle Mariners have played since 1977 has dramatically overshadowed the Pilots, making them a footnote far more interesting for their messy management than any on-field accomplishments. Though postseason success has eluded them, the Mariners have nevertheless rostered some of the most iconic ballplayers of the past few decades, including Randy Johnson, Ichiro, Ken Griffey Jr., and Félix Hernández. These were all superstars, beloved and appreciated not just locally but internationally. Even today those are still the names that populate the backs of jerseys in Mariners crowds.

But long before any of these men made their mark on baseball in the Pacific Northwest, Seattle had a different favorite player. He wasn't much of a hitter, and his team wasn't much of a winner. But they loved him anyway.