In the spring of 1994, a Silicon Valley executive named Steve Hams decided to start a women’s basketball league in the United States. What Hams lacked in sports business experience, he made up for in optimism and sincere desire to correct what he considered the great tragedy of the women’s game. It troubled him that the Stanford stars he liked watching with his eldest daughter graduated with only two options: to bounce around leagues overseas or to leave basketball altogether.

At least a half dozen attempts at professional women’s basketball had been made in the previous two decades, none with any success. But the failed leagues of the past, Hams thought, might simply have been ill-timed. There looked to be a real, untapped market for women’s sports at the moment. Athletes of the “Title IX generation” had blossomed into superstars with apparel contracts and endorsement deals. Young girls and their parents shelled out money for tickets and jerseys. At the collegiate level, women’s basketball even brought in modest revenues for a few schools.

As he worked on a business plan, Hams began looking for like-minded partners. He found one, in February of 1995, in a local business journal article about a public relations executive named Anne Cribbs.

A swimmer in the 1960 Rome Olympics, Cribbs knew the pains of being a woman athlete all too well. It happened, too, that she’d been imagining new possibilities for women’s basketball lately. On the same day a rookie Chris Webber signed his first NBA contract, worth tens of millions—two years before she got a call from Steve Hams—Cribbs was at a mall in Palo Alto, searching for a pair of socks with her daughter, Alexandria. As the two browsed, Cribbs recognized the clerk in the sporting goods store as the two-time NCAA champion Molly Goodenbour, who had shot her Stanford team to a title in 1992. (Webber’s infamous timeout mishap had cost his team a title, Cribbs points out.) The sight of Goodenbour making minimum wage devastated Cribbs. On the sidewalk outside, in the California autumn, she sighed and told her daughter something was very wrong with the world.

Cribbs and her business partner Gary Cavalli, who counted Stanford Athletics among their clients, had joked at games over the years about starting their own women’s basketball league. “But neither of us had any money, so that kind of kept the discussion to a minimum,” says Cavalli. “And then all of a sudden, here comes Steve.”

The three—“West Coast yahoos,” Cavalli calls them—met to brainstorm at Hobee’s, a sort of health-conscious family restaurant on El Camino Real that February. Though Cribbs and Cavalli knew it needed some refining and big names attached, they were impressed by the broad contours of the plan.

An HR guy by trade, Hams had studied the shuttered leagues carefully and found clear patterns in the failures. In the Women’s Professional Basketball League of the late ‘70s, the relationship between players and executives was one of distrust. By the WBL’s last year, teams were staging walkouts to protest missed paychecks and shrunken meal budgets. Other leagues, like the Liberty Basketball Association, which played just one game in 1991, had relied on cruel gimmicks, forcing players into uncomfortable, sexualized uniforms to make them attractive to the American consumer.

If the goal of the new project was to keep women stars from disappearing across the Atlantic or behind the counters of department stores, it would need to offer a stable and respectable alternative. Hams’s plan called for players to earn competitive salaries with year-round benefits in a regular fall-winter basketball season. This league would be a real, full-time job, and if women could devote their full attention to the domestic league, it followed that the product would be better. The plan described setting up teams in towns with strong women’s college basketball followings, ensuring a built-in fan base already enthusiastic about the sport and not likely to take much issue with the way women athletes looked or presented themselves. Hams envisioned close and constant collaboration between executives and players, who would each have some ownership stake in the league. In his mind, doing right by the players was the only way to make this work.

Laying claim to a sport, however, is not so simple as putting principles to paper. Before long, Hams, Cribbs, and Cavalli would be drawn into an exhausting fight against a powerful enemy, one they weren’t prepared for. It was the kind of fight in which big, admirable, ambitious dreams never stand a chance.

Crucially, the new league had the perfect peg. The 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta were around the corner, and the best American women’s players were training together for a year under the esteemed Tara VanDerveer, on sabbatical from her head coaching job at Stanford. Still bruising from a lackluster bronze finish at the ‘92 Olympics, USA Basketball had arranged for the women’s national team to play a 22-game college tour around the country and a series of international matches to prepare. The transcendent talents this league needed were, conveniently, already poised to enter the American public eye.

If they’re offering me a contract, they’ve gotta be doo doo.

Valerie Still

Cribbs and Cavalli met one of them, Jennifer Azzi, at a dinner their firm planned for the Stanford Athletics Hall of Fame inductees in June. Cavalli rearranged the seating chart so he’d have Azzi’s ear for a few hours, and the former star point guard heard his pitch before the chicken dinner was served. She asked Cavalli politely, if not too enthusiastically, to send her the business plan. After reading it that week, Azzi called to say she was in.

Next came Teresa Edwards, a decorated Olympian who’d played in Europe and for the Mitsubishi Electric Corporation team in Japan. Edwards was skeptical at first—she’d heard of the preceding failures—but Hams, Cribbs, Cavalli and Azzi won her over. “Once we had Jennifer and Teresa, that was a huge step forward,” Hams says. The two Olympians encouraged their teammates to take meetings with Hams, and he traveled the country to lobby each one. By the end of the year, nearly every member of the ‘96 team had committed to playing in the new league after the Olympics. The lone holdout, dewy UConn graduate Rebecca Lobo, didn’t want to rush into anything.

However fledgling the idea, the ‘96ers felt they had little to lose by coming aboard. A “successful” basketball career for American women had until then constituted a cycle of disappearance and fleeting emergence in Olympic years, and the 31-year-old Edwards, by then a veteran of three Olympic Games, was tired of that rhythm. Point guard Dawn Staley, now a Hall of Famer and head coach at South Carolina, says she was “elated, champing at the bit” for an opportunity to play again in front of her friends and family, and not overseas, where American players often felt lonely and unstable. “It’s hard to describe how hopeful we were, even if this thing was just a packet of paper and Steve was some guy we didn’t know,” Azzi later told the journalist Sara Corbett.

Early on, at a weekly all-staff meeting to review the PR firm’s new accounts, someone asked Cribbs and Cavalli about the likelihood this league would get off the ground. “Oh,” Cavalli answered. “I’d say about one percent.”

As players signed on and sponsors showed interest, that number grew. The packet of paper slowly became something real: the American Basketball League, a name the players liked because it didn’t cast the “women” element as anything out of the ordinary. “Why would we put a ‘W’ on there? They don’t put one on the men,” says Sylvia Crawley, an alternate on the ‘96 team.

Details as tiny as those were always up for discussion. Hams asked the players to weigh in on everything from how teams should draft players to the proper length of the jerseys. “Before a decision was made, I was in on the conversation,” says Staley. “It allowed you to be invested in the league instantly.”

Still, enthusiastic participation of almost the entire national team notwithstanding, finding investors proved a challenge. Hams spent about a year in total “dialing for dollars,” pleading the ABL’s case to the bookstore founder Louis Borders, Martina Navratilova, and a few hundred others. The responses were universally admiring, but no one wanted to take the risk. An initial lifeline came, finally, in the form of Bobby Johnson, an impeccably dressed Atlanta businessman so inspired by his daughter’s AAU games that he’d gotten in touch with Teresa Edwards to ask how he might make women’s pro basketball a reality in the U.S. By the fall of 1995, Johnson had agreed to invest about $3 million in the ABL.

Women’s basketball can be hostile to outsiders. The people who watch, play, and coach it zealously guard the game’s image, feel a deep stake in its future, and expect the same of anyone else who claims to be a fan. As women’s basketball reached new heights in the ‘90s, the protective impulse only became stronger. In other words, not everyone took kindly to three inexperienced West Coast yahoos and an Atlanta nursing home operator starting their own league.

“People all over the world, all over the United States, in the women's basketball community and the media, saying we had no chance, that this thing would never happen,” Cavalli says.

The doubters were about to win another point. Flanked by the NBA’s vice president of business affairs, Val Ackerman, at a press conference in New York in April of 1996, NBA commissioner David Stern promised fans “the world’s best women in the world’s best arenas.” The NBA’s Board of Governors had voted to launch its own women’s league, a summer league scheduled to begin play in 1997. This time, women’s basketball would succeed. As Stern put it, “We don’t enjoy failing.”

An ESPN executive privately told Cavalli, now the ABL’s CEO, that he wondered if the network was backing the wrong league.

The ABL execs scrambled to turn the national team members’ verbal commitments into something binding. A week after the NBA’s announcement, the ABL was missing just three signed contracts: from Rebecca Lobo, who had never committed to the ABL at all; Sheryl Swoopes, recent namesake of a Nike signature sneaker; and Lisa Leslie, a Wilhelmina model eager to play on a summer schedule that would allow her more time for modeling (and in a league signing her to a rumored two-year, $1 million contract).

Not ideal, certainly, but Hams, Cribbs and Cavalli knew this had been a possibility; for years the NBA had been coy about its intentions with women’s basketball. If only to self-soothe, Hams chose to be optimistic. The two leagues had non-conflicting schedules and what the ABL lacked in money, surely it made up for in talent. Why couldn’t both survive?

A few months later came the cheering up the ABL execs needed. In a gym smelling of “leather, sweat and 20 different deodorants,” as former WNBA player Fran Harris recalls in her memoir, nearly 600 women tried out for the ABL, some of them in their 40s. Players were drafted by the league’s eight founding teams, all given names that, if nothing else, signified the decade: Atlanta Glory, Columbus Quest, Colorado Xplosion, San Jose Lasers, Seattle Reign, Richmond Rage, Portland Power and the New England Blizzard. At that week’s staff meeting, Cavalli updated his estimate to 50 percent.

Only four months separated the draft and the beginning of the ABL’s inaugural 40-game season in October. Building a franchise from scratch in such a short span was the challenge of a lifetime for Pam Batalis, who left her job in sales at Reebok to be general manager of the New England Blizzard. “Flash back to 1996. We had a sundial and an abacus and an 8-track tape player to communicate the launch of our team,” she says.

A former college basketball player herself, Batalis was so excited by the idea of a professional league that she couldn’t not be part of it. She throws around the words “mission,” “passion,” and “pioneers” when recalling her experience. The days were long—hiring a staff, mascot selection, coordinating in-game entertainment—and there was nothing she’d rather be doing. “I think I averaged probably three to four hours of sleep a night, lost 20 to 30 pounds, worked out every single morning at the crack of dawn or at midnight, and didn’t even think twice,” says Batalis.

4,600 people packed the San Jose State Events Center to watch the opening night ABL game between the Lasers and Glory, which featured Azzi and Edwards, both back from their gold medal finish in Atlanta. For Cribbs, seeing ticket scalpers outside was a sign this just might work. “What you saw tonight is just the beginning,” Azzi said after the game, a Lasers win. ABL staffers showed up that night in T-shirts that read “100%.”

The league was blessed with an inaugural Cinderella story. Before the season started, not much was expected of the Columbus Quest, a team so lacking in starpower that most members of the press projected them to finish last. A few players drafted to the team—their aversion to Ohio outweighing their dreams to play professionally—didn’t show up at all.

The team was coached by Brian Agler, an attentive and exacting coach. At his practices, which he admits were tougher than the games, Agler saw to it that every player got repetitions on offense. More notorious were his elaborate defensive drills, which each produced a “winner” and “loser” to keep the team competitive.

Soldiering through this all was Valerie Still, an undersized center at 6-foot-1 in the twilight of her career. Still left the University of Kentucky the school’s all-time leading scorer and rebounder in 1983. Against her mother’s wishes, she put her veterinary school plans on hold to move to Italy, where she spent 12 seasons playing professionally. She married a fellow basketball player there, and after they moved back to Kentucky, Still had a baby.

One of Still’s former college assistants convinced her to drive three hours from Lexington to Columbus (she had to stop to buy sneakers along the way) to try out for the Quest. When she arrived, in a large shed-like building without air conditioning, Agler threw her into a five-on-five scrimmage she found a bit exhausting. She was getting ready to slip out the door when Agler told her he wanted to offer her a contract.

Still didn’t take this as an encouraging sign. “If they’re offering me a contract, they’ve gotta be doo doo,” she says. The contract was too nice to pass up, though. The $75,000 salary was generous, it came with stock options, and she’d be allowed to bring her son to every practice and game, home or away.

From there things kept getting better: the Quest weren’t actually doo doo. Agler had assembled a pretty perfect squad. Olympian Nikki McCray went on to win MVP that season. Steady veterans Still, Sonja Tate and the ‘88 Olympian Andrea Lloyd played alongside gutsy rookie finds Shannon “Pee Wee” Johnson of South Carolina and Ohio State’s Katie Smith, the Quest’s territorial draft pick, whom Agler calls the greatest women’s player ever to come out of Ohio.

Together, the Quest played a physical but strikingly fluid, contemporary game, up-tempo and prone to fast breaks. “It was highly athletic, there were no weaknesses on the floor,” says the broadcaster Debbie Antonelli, who called games for Fox SportsNet. To fans’ delight, Quest players dove for loose balls, even in garbage time. Offensive harmony and aggression on defense led them to enter the postseason with a league-best record of 31 wins, though average attendance was a league-low 2,500 a game.

In the 1997 ABL Finals, they struggled against Dawn Staley and the Richmond Rage, which Staley remembers being a fiercely competitive team of great communicators. “We had all the key ingredients to winning an ABL championship,” Staley says. When the Quest arrived at Richmond Coliseum to practice before Game 4, down 2-1 in a best-of-five series, they even caught sight of the Rage rehearsing the trophy presentation with league officials.

The night before the game, Still sat awake in her hotel room with Tate, her best friend on the team, as a 2:00 a.m. replay of Game 3 played on BET, the only other network airing the ABL. The two watched an advertisement announce that the ABL’s Finals MVP would win a Nissan Altima. Still turned to Tate and declared she was going to win the car for her mother.

The Quest beat Richmond by 11 points in Game 4, and won again decisively back home in Game 5. “Now I know what Michael Jordan feels like,” McCray told the Washington Post. Valerie Still got her car.

The WNBA kicked off its inaugural season a few months later, in the summer of 1997. Some differences were apparent from the start. Aside from the Olympians, the talent pool was shallow. “WNBA rosters had players that were pretty on the margins in terms of being able to play professional basketball,” says Michelle Smith, who covered women’s basketball for the San Francisco Examiner. When the New York Liberty and Los Angeles Sparks played the first WNBA game at the Staples Center in June, the teams combined for 44 turnovers and the Sparks shot just over 30 percent from the field. An ESPN executive privately told Cavalli, now the ABL’s CEO, that he wondered if the network was backing the wrong league.

It didn’t help the WNBA’s reputation that much of its promotional material centered not on play but on its three charming marquee players, one of whom, Lisa Leslie, embraced the role of stylish spokeswoman. “I think it’s important for girls to know that they don't have to look like boys to play like boys,” Leslie told a reporter. One San Jose Mercury News columnist likened the difference between the WNBA and ABL to the difference between Cosmo and Ms. Magazine.

But the WNBA was winning the war that mattered. It had TV deals with Lifetime, ESPN and NBC, and higher than expected average crowds around 10,000. The likes of Penny Marshall and Rosie O’Donnell were sitting courtside. An ABL game, by contrast, was a decidedly more intimate experience. Players hung around after games to chat with kids in attendance. Seattle Reign player Kate Starbird remembers personally calling fans to ask them to renew their season tickets.

The competing leagues brought the sport’s fissures to light. Which one could shepherd women’s basketball forward? Was idealism, a refusal to compromise, financially viable? On the women’s basketball internet, the questions were answered a thousand times in a thousand ways, with exactly the level of decorum and coherence you’d expect from people devoted to an unsung sport and compelled to prove this devotion online.

The ABL hosted its own tame Fan Forum on ABL.com, where referees and team officials sometimes popped in for live chats. Teams set up websites and listservs for fans to organize watch parties and recap games. But the real action happened on the lively rec.sport.basketball.women Usenet newsgroup, which brought a thousand or so of the most zealous, protective ABL and WNBA fans together to close-read quotes in daily newspaper columns, guess wildly at each league’s financials, and bicker about the league’s competing models in threads titled “Stop the bickering!” Fans of the ABL chided the WNBA for playing “when the boys weren’t using the gym.” They pointed to salaries the WNBA was paying ($15,000 to $50,000), in relation to the ABL’s ($40,000 to $100,000 with year-round benefits). Online, ABL fans nicknamed the competing league the wNBA; to them, the Association loomed large and the women were incidental.

“[The WNBA] just wasn’t being fair to the women,” says Gay Katilius, a Lasers season ticket holder and listserv denizen. “They weren’t paying them a living wage and the players had to go out and have another job in addition to playing basketball. It just seemed like it was a slap in the face to women.”

The players kept their own opinions offline, though they watched these spats, sometimes with mild amusement. “It’s incredible the stuff that’s on there,” the Quest’s Andrea Lloyd told the Spokesman-Review. “And these people are going at each other. They’ve chosen sides and it’s a battle.”

Strapped for attention in its second season, the ABL was a league desperately in need of a gimmick. To Cavalli’s dismay, only once had ABL news cracked the ESPN ticker: when New England’s Clarissa Davis-Wrightsil punched Seattle’s Cindy Brown square in the head during a scrap for a rebound. So in January, Cavalli proposed a joint ABL-WNBA All-Star Game. Val Ackerman, the David Stern protégé who had been named the WNBA’s first president, declined, calling the idea “a one-time publicity stunt that in the end isn't good for women's basketball” in her response by letter. (Per the message boards, this was just as well, because the women of the ABL would’ve kicked Rebecca Lobo’s ass.)

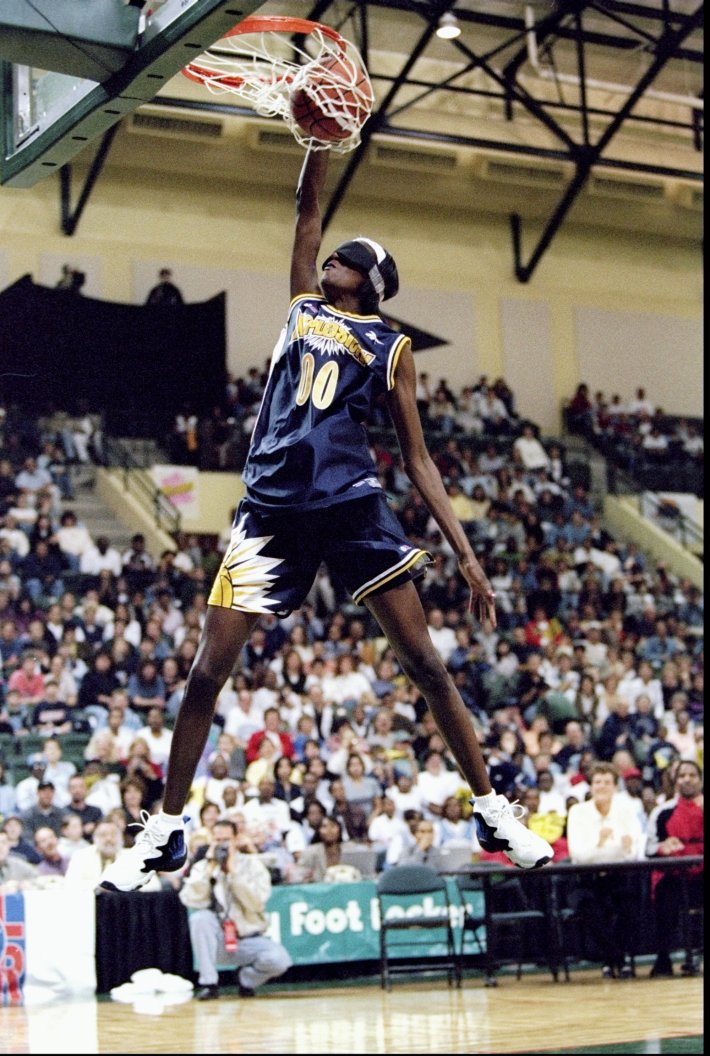

The pursuit of publicity could sometimes backfire. When Xplosion star Sylvia Crawley pulled off a blindfolded dunk to win the dunk contest at the ABL’s second All-Star game—an event that was cooked up in the hopes of grabbing some national attention—she was pulled into a room by her agent afterwards. The NBA was on the line. People there had seen her dunk. They thought Crawley had the makings of a WNBA star and wanted to know what her price was.

She hardly had a minute to think before Cavalli came inside to ask what she would need in her next contract to stay. Crawley huddled with her agent, boyfriend and sister, told Cavalli her answer, and walked out of the meeting poised to be the highest paid women’s basketball player in the world.

Bidding wars like this were becoming routine. “Every time a player’s contract came up, if it was somebody that had caught the media’s fancy, the NBA would come after that player with guns blazing and we’d have to up the ante,” says Cavalli.

ABL leadership took some comfort in theirs being the deeper and more mission-driven league. Val Whiting didn’t accept a WNBA offer because she’d have to return to playing overseas for most of the year. “I wasn’t really ready to do that again,” Whiting says. “I was also convinced that the better players were in the ABL and I wanted to play against the best competition.”

“But talent always goes to money,” says ESPN’s Mechelle Voepel, who covered both leagues. College stars and ABL free agents found it hard to resist the prospect of NBA glamour. Columbus’s Nikki McCray left the ABL after her one-year contract ended. She signed a three-year, $200,000 contract to join the WNBA’s expansion team in Washington, D.C., where her face was soon plastered across ads in Metro stations and on television. Within a year, she had her own Fila sneaker, which she told the Washington Post made her “the happiest I’ve ever been.” Her former teammate Valerie Still complained, a bit naively, in Sports Illustrated: “What ever happened to loyalty?”

Still’s coach, Agler, left the ABL after winning a second championship with the Quest to coach the WNBA’s Minnesota Lynx, a decision he based on “the inevitable.” Staley also made the switch then—not for money or because the WNBA seemed more viable, she says, but because she wanted a schedule less taxing on her troublesome knees.

As the upstart league spent feverishly to ward off what Cavalli called the 800-pound gorilla, the ABL’s costs ballooned. Few players still believed two women’s basketball leagues could sustainably co-exist. A merger like the NBA and ABA’s seemed the probable and imminent outcome, but on whose terms, nobody knew.

Running a league was proving to be more challenging than anyone could have imagined that morning at Hobee’s, but there were moments when the toil seemed a small price to pay. At a high school basketball game one weekend, Hams’s daughter squinted at the court, and said to her father with a scowl, “I didn’t know boys played basketball.”

As it happened, men weren’t playing basketball at the start of the ABL’s third season. Months of discussion over a proposed salary cap system had curdled into a standoff between the NBA and the players union. The entire preseason was cancelled, then the first two weeks of the regular season. The ‘98 lockout would become the longest stoppage in league history at 191 days.

Here was a moment for the ABL to step in, drawing the fundamental (if now passé) contrasts it liked to—not between itself and the WNBA, but between basketball’s devout women and its bickering men. A public television documentary about the ABL does this with all the subtlety of Clarissa Davis-Wrightsill’s punch to the head: An audio supercut of news clips tells of Michael Jordan’s net worth, the bitter lockout, Shaquille O’Neal’s Lakers contract. The decadence of the men’s game now evoked, a girl with a basketball tucked under her left arm trudges to an empty court.

Millions of people were ostensibly eager to watch basketball, and several TV stations were ostensibly ready to broadcast it. A vacuum waited to be filled. Seattle’s Key Arena, bereft of the Supersonics, agreed to host a Lasers-Reign game that would become one of the more memorable contests in ABL history, a double overtime thriller so loud one player said her head felt like it was “about to explode.”

If I had a dime for every person who said they’d want to invest in the ABL, I’d be sitting on a luxury liner somewhere, sipping piña coladas for the rest of my life.

Gary Cavalli

A few weeks after she played in that game, three days before Christmas of 1998, Kate Starbird went to a doctor’s office to have an MRI done on her knee. The injury was bad enough to keep her from playing for the next two months, which would have been crushing news for the postseason-bound Reign. As it turned out, that wouldn’t matter. She emerged from the scanner, glanced at her cell phone and noticed a curious number of messages. Had she heard? Cavalli had pulled the plug. The ABL was bankrupt.

“Nice Try, No Reward,” the New York Times headline read.

“If I had a dime for every person who said they’d want to invest in the ABL, I’d be sitting on a luxury liner somewhere, sipping piña coladas for the rest of my life” Cavalli says.

The ABL had lost $5 million in its first season and $4 million in its second. Entering the third, with each team’s payroll at about $900,000, Cavalli was anxious about money and about the fact that promising conversations with investors kept fizzling out.

So anxious that he resorted to extreme measures. In the summer of 1998, after consulting with the ABL’s board, Cavalli asked to meet with Ackerman. Over a long lunch at a New York hotel, he suggested merging the ABL and WNBA. Ackerman told him she would take the offer back to the NBA but wrote Cavalli a few weeks later to say the idea wouldn’t work. “A merger wasn’t of interest to the NBA, which at the time was comfortable with the model we constructed and didn’t feel a need to join forces with any outside group,” Ackerman writes in an email.

What the ABL still needed badly to compete with the WNBA was television exposure. With one of the ABL’s biggest investors, Joe Lacob, the now-Warriors owner who then served as owner-operator of the Lasers, Cavalli made the rounds with major networks in New York, offering to pay millions for the airtime. “They were all very receptive, very nice, very polite, but they were all afraid to offend the NBA, so none of them would do it,” Cavalli says. Only CBS agreed to the deal, and just for a few games in the playoffs. Around the same time, Cavalli also asked the players’ advisory board about reducing player salaries, an idea that went over poorly.

Hams began to accept that the ABL was not long for this world sometime in November, about a month before the league folded. Not wanting to distract the players, the execs didn’t involve them in discussing the finances. As the ABL played the season, it became apparent that the opportunity of the NBA lockout was no opportunity at all. Attendance didn’t budge; nothing changed. “I don’t bullshit people. I don’t exaggerate. I don’t lie,” says Cavalli. And he was finding it harder and harder to tell people that everything was OK.

He may have let it slip once that things were not. A few months after the ABL declared bankruptcy, The New York Times ran a post-mortem of the league featuring Allison Hodges, the GM of an ABL expansion team in Chicago and wife of the Chicago Bull Craig. She described getting a call from Cavalli the previous April on her way to a press conference at Michael Jordan’s Restaurant, where she planned to announce the team’s name.

“Craig and I were in the limousine on the way to the restaurant and we got a call on my cell phone from Gary,” she said. “He told me to cancel the press conference because the league was going under.” As Hodges remembered it, Cavalli called back a few minutes later to say, “Go ahead and have a drink on me; I think we're OK.”

“I definitely told her we were having some financial issues,” Cavalli says. “I did not say ‘the league was going under, don’t do the press conference.’ I talked to her about postponing it.”

In December, when Cavalli no longer felt confident he could send a team on the road and cover its hotel bills and airfare, he went to the ABL’s board with what seemed to be the only choice left. They all agreed, pretty quickly, that the ABL couldn’t go on.

Val Whiting found out about the league’s folding when a reporter called her to ask for comment. She and her Reign teammates came back from their Christmas vacations to a dreary Seattle winter and went to stand in the unemployment line together.

Crawley wasn’t angry, but she did feel a little foolish for having no résumé or backup plan. In hindsight, she felt she should have seen the bankruptcy coming. She had noticed that they were staying in more modest hotels than they had been in the first season. Somewhere down the line, the charter bus to the airport had become a van to the airport had become “everyone can just meet at the airport.” She vowed never to put all her eggs in one basket again.

“We are proud of what we accomplished as a pioneer in women's professional athletics,” Cavalli said in the press release. “We put a great product on the floor. We gave America's best women athletes an opportunity to play professionally in this country during basketball season. We gave it our best shot; we fought the good fight, and we had a good run. But we were unable to obtain the television exposure and sponsorship support needed to make the league viable long-term.”

In the bankruptcy filing, the ABL claimed debts of more than $10 million, including $750,000 in unpaid wages and $2.8 million owed to ticket holders.

A few lawyers suggested one possible means of revenue: Why not file an antitrust suit against the NBA? They were interested in the idea, but after a while, Cribbs, Hams and Cavalli didn’t feel much up to it. “You have to decide when it’s time to call it quits,” Hams says. There were no smoking guns, just vague recollections of them: a conversation with a ball manufacturer who’d alluded to a call from the NBA; a conversation with a network executive who rebuffed the ABL, citing “relationships.” In everyone’s memory loomed the pyrrhic USFL case, a reminder that putting up a fight against the titans of sports is seldom worth the hassle. Connecticut’s then-attorney general Richard Blumenthal opened an investigation into whether the NBA used “sharp economic elbows” to exclude the ABL from competition, but closed it quietly a few months later, having made little progress.

Katilius, the Lasers fan, was devastated by the ABL’s folding. She had been especially looking forward to that season’s All-Star game in San Jose, so she quit her job and organized a charity game herself at a gym at DeAnza College in two weeks. Everyone was there: Azzi, Edwards, Starbird on her balky knee, even Klik the Mouse, the Lasers’ mascot, an eerily beautiful galactic rodent in high tops.

Lasers coach Angela Beck, who coached that game, remembers vividly “the heartfelt feeling that you had, watching something come to an end.” The event sold out, with tickets going for up to $1,500.

“Women are victims all the time,” Katilius told a reporter after the game ended. “Things happen to us that we have no control over. I just wanted to write a happier ending.”

Have you ever believed deeply in something, staked your livelihood on it, and then watched it die? It is so embarrassing and so unfair.

Sylvia Crawley, to her own surprise, was not selected in the 1999 WNBA draft. The WNBA players’ union fought for a restriction on ABL players allowed to join the league, and was granted one at 40 spots. One of those, Crawley’s agent reassured her, was hers. On draft night, the WNBA let Crawley know of a two-hour window in which she should expect The Call. She waited by the phone; the two hours came and went. The woman who once dunked blindfolded sent her friends and family home and spent the evening sobbing into the carpet. Still, the two-time ABL champion, went undrafted, too.

A gloomy night all around: The unlucky college seniors entering the draft stood no chance against a pool of seasoned professionals. One All-American point guard out of Colorado State, easily drafted in any other year, watched in tears as the night passed her by. (Becky Hammon would turn out to do just fine for herself.) Even the ABLers who made it to the WNBA felt a sense of loss. At WNBA players’ orientation, ABL player Edna Campbell was saddened to see so many of her deserving teammates missing from the room. As Whiting remembers it, David Stern snapped at Campbell for being upset.

For most of the ABL’s players and coaches, it was back overseas or on to other things. Angela Beck interviewed for a few WNBA coaching jobs and thought she’d found one when the team abruptly reneged the offer. Sorry for the inconvenience, they said, but they’d found a man with no experience for the job, and would she instead want to be the man with no experience’s assistant? “I’d never been an assistant in my life,” she says. She told them no.

Teresa Edwards, her career so long and decorated that a rookie ABL teammate of hers grew up with an Edwards poster on her bedroom wall, refused to sign with the WNBA. In her mind, she couldn’t justify playing for a WNBA salary, about half of what she’d made in the ABL. She went back to Atlanta and spent six hours a day at a Crunch gym, training for her fifth and final Olympics. By 2003, Edwards changed her mind. She was drafted by the Minnesota Lynx at the age of 38.

Some NBA franchises treasured their women’s teams. Others just tolerated them. One of Starbird’s coaches in the WNBA—she suspects he had never watched women’s basketball before—suggested the team ease up on perimeter defense because women could not shoot three-pointers anyway. She remembers her teammates being pulled off the court at practice so the men’s coaches could work out D-League players. “There were some times,” Starbird says, “where you felt the weight of being a little sister team.”

Maybe that’s what the women’s game has resigned itself to under the auspices of the NBA. Begin from the maw of compromise and you wither there. Ask men to legitimate you and you are only asking to be overshadowed. When Whiting watches WNBA games these days, she notices broadcast crews interviewing Chris Paul or John Wall sitting courtside, and sees all too plainly who’s the star and who’s being done the favor.

As a girl, Whiting never gave much thought to the idea of professional women’s basketball in the U.S. She grew up studying and admiring men’s players, James Worthy, especially. In Whiting’s house, women’s games aired on television just one time a year, during the Final Four, and she’d keep the games on tape to watch over and over until the next year. In other words, the bar for improvement was always low. The WNBA asks its players to supplement their small incomes overseas and to risk injury in the year-round toil. It still holds its season when the boys aren’t using the gym and contends with the NBA’s neglect. More than 20 years later, the fight waged and won, the longest-running professional women’s sports league can get away with what it inflicts on players because everyone knows suffering those indignities is better than nothing at all.

But for two and a half years, the sport’s imagination was bigger. There existed an alternative that wasn’t nothing at all: a league that believed great athletes warranted investment and attention and tried, however doomed or risky the attempt, to deliver. Those who loved women’s basketball caught a glimpse of a future in which it was stewarded by people who cared deeply for it and only for it. In that unrealized future, women’s basketball was no longer a flimsy, nomadic pursuit, but a real, rewarding profession. They saw, briefly, what it might be like for women to play on terms of their choosing.