One city wasn’t big enough for two teams, and it feels, with the benefit of hindsight, like it was destined to turn out the way it did.

The Cardinals became the class of the National League, as much a part of St. Louis as toasted ravioli and the Gateway Arch, playing before the self-appointed Best Fans in Baseball in a sea of red, honoring a rich history of more World Series wins than any team that doesn’t play in the Bronx.

The St. Louis Browns, on the other hand, were a sideshow, a moribund team more known for its curiosities—a pinch-hitter less than four feet tall, and a one-armed outfielder—than any actual on-field skill. The only AL Pennant for the Browns came in 1944, when World War II had depleted the ranks of the major and minor leagues. Those Browns were known as the 4Fs, for the number of players they had—which in 1945 included Pete Gray, the aforementioned one-armed outfielder—that met that draft classification: unfit for military service.

If any team was going to leave town, it would be the Browns, who indeed became the Baltimore Orioles in 1954. It seems impossible to imagine the Cardinals in any city other than St. Louis.

It was closer than you might think.

When the American League started play in 1901, Milwaukee had a team—the Brewers. The team lasted a year before moving to St. Louis and becoming the Browns, an homage to the local Cardinals’ former moniker, the Brown Stockings. In 1903, the Baltimore Orioles moved to New York and became the Highlanders, later more famously known as the Yankees. That was the last piece of the puzzle for the two major leagues to take shape, and the structure endured for the next half-century. There were 16 teams—eight each in the National and American Leagues, representing a total of 10 cities.

That meant five cities each had multiple teams: New York (which had three, counting Brooklyn, which had become part of New York City just five years earlier), Chicago, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Boston. In that order, they were the five biggest cities in the country. In 1904, St. Louis was poised to host a World’s Fair and ended up with an Olympics too. (The Games were officially awarded to Chicago, but St. Louis planned to have its own athletic competition to coincide with the Fair, and rather than compete with another Midwestern city, the Olympics were moved. Nearly 120 years later, Chicago is still waiting for a chance to host.)

In the early days, the Browns were the more successful and popular of the city's ball clubs, thanks in no small part to an utterly mediocre catcher whose skills, as it turned out, lay in management. Branch Rickey played briefly for the Browns before heading off to law school at the University of Michigan. He returned to the team in 1913 as manager, ultimately bringing with him an Akron native who’d played for him as a freshman at Michigan: George Sisler.

Sisler, a first baseman, would go on to a Hall-of-Fame career, almost entirely with the Browns. As for Rickey, he had more stops to make. The Browns were sold to Phil Ball in 1917. Rickey had signed a long-term contract with the Browns, but he and Ball clashed, and Ball was delighted to let him go. In 1919, Rickey went across town to the Cardinals. The next year, Ball made his second-biggest mistake: He let the Cardinals use Sportsman’s Park as a tenant.

It was then that the worm started to turn.

Rickey, as Cardinals general manager, started the minor-league farm system. It had been done on a smaller level before (Charles Somers, the Indians’ first owner, had stakes in several minor-league teams before financial reversals forced him to sell those teams and eventually, his big-league club), but Rickey used it to unearth and hang on to talent that would keep the Cardinals stocked for decades to come.

The Browns finished in second place in 1922, winning 93 games. They’d never win that many again. Meanwhile, in 1926, the Cardinals made their first trip to the World Series, beating the Yankees in seven games. The Cardinals returned to the World Series in 1928 (a loss to the Yankees), 1930 (a loss to the Athletics), 1931 (a victory over the Athletics) and 1934 (a victory over the Tigers).

Detroit made an impression on Cardinals owner Sam Breadon, who realized that St. Louis wasn’t a two-team city anymore. In fact, in 1932, the Cardinals were outdrawn by their top minor-league affiliate, the Columbus Red Birds, who were playing in a new stadium and taking full advantage of night baseball, at the behest of wunderkind Larry MacPhail, who had bought the team—and then promptly sold it to Rickey as part of his burgeoning farm system.

By the 1930 census, St. Louis had fallen to the seventh-biggest city in America, eclipsed by Cleveland, Los Angeles, and Detroit, the latter a boom town almost twice St. Louis’s size. Speaking during spring training in 1935, Breadon suggested that he would be willing to leave St. Louis to the Browns and relocate to Detroit—if Tigers owner Frank Navin didn’t object. Breadon later walked back his remarks, but the word was out that the Cardinals were looking.

“The time may not be far distant when the Redbirds will be flying away to some other community,” wrote the Sporting News. Four years later, the Sporting News wrote that during owners’ meetings prior to the All-Star Game at Yankee Stadium (another example of a team getting out from under the thumb of its landlord at a shared ballpark, as the Yankees had toiled at the Giants’ Polo Grounds for a decade), serious consideration was given to the Cardinals moving to Columbus.

(A half-century later the football Cardinals, then in St. Louis, also considered a move to Columbus before going into the desert in Arizona. There was a joke in Ohio that if Columbus got a pro football team, pretty soon Cleveland would want one too.)

Breadon wouldn’t have to ask for permission to move to Columbus, since the Cardinals controlled the area’s territorial rights. But it remained a lucrative site for minor-league baseball. A month later, Breadon officially announced that the Cardinals were staying put in St. Louis.

Now it was the Browns’ turn to start looking. Harry Arthur, a minority owner from California, touted Los Angeles as a possible destination for the Browns. A.P. Giannini, the founder of Bank of America, pledged financial backing, and 500,000 ticket sales were promised the first year. Even Breadon was willing to put up $250,000, just to have St. Louis to himself. Travel logistics were worked out with TWA and the Santa Fe railroad. Gradually, Browns majority owner Don Barnes was convinced, and he was set to present his case to the other owners. It seemed sure to pass—sure enough that the Browns’ owners had already planned a news conference to announce the move to L.A. It just had to be voted on by the owners, who were meeting in Chicago on Dec. 8, 1941.

The afternoon before, Barnes was at a football game at Comiskey Park when word came over the PA system that the U.S. Naval base at Pearl Harbor had been bombed by the Japanese. “With the scare of a West Coast invasion,” Barnes recalled later, “we realized at once that Los Angeles was no place for the Browns. Our dream was shattered.”

Barnes gave his presentation the next day anyway—and then asked that it be rejected. The vote was unanimous against the plan. The Browns weren’t going anywhere.

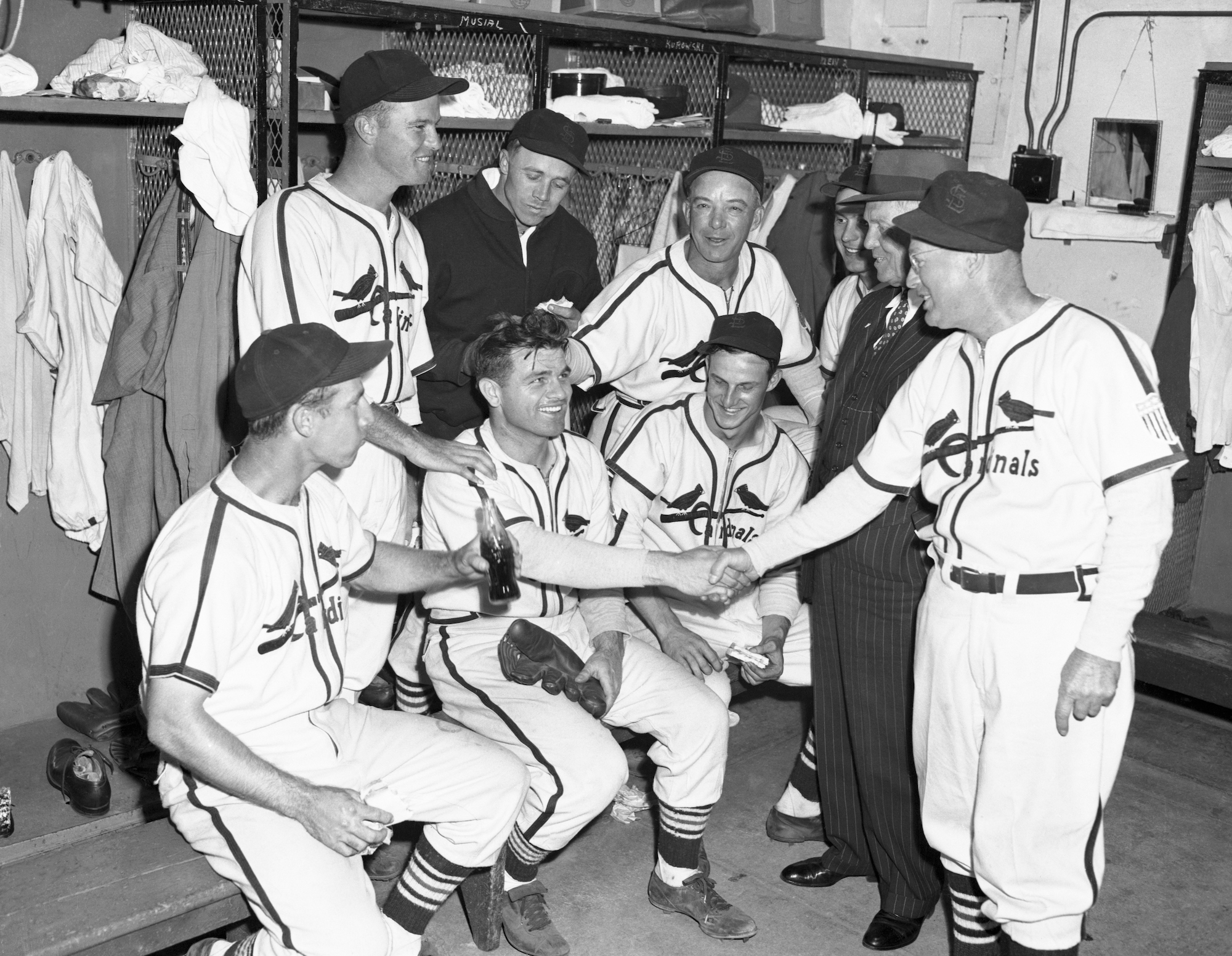

As it turned out, neither were the Cardinals, who won the first of three straight pennants (and four in a five-year span) in 1942. They went on to beat the Yankees in the World Series with a team of home-grown talent from Rickey’s farm system, including Stan Musial, Enos Slaughter, and Marty Marion. By this time, Rickey was on his way out the door. His relationship with Breadon had become strained, and he was on his way to Brooklyn, where he’d build another dynasty, in part by raiding the Negro Leagues for talent.

In 1944, Sportsman’s Park became only the second ballpark in history to serve as home team for both teams in a World Series. The Browns had strung together 89 wins, good for the American League pennant—at the time, the lowest win total for a pennant winner—but lost the “Streetcar Series.”

Flush with success, Breadon announced following the 1944 season plans to build a new ballpark for the Cardinals. The land had been acquired, he said; all that had to happen was for World War II to end. The Cardinals' lease at Sportsman's Park would end in 1951. But postwar shortages delayed construction, and Breadon’s interest wavered as he made plans to sell the team. Fred Saigh bought the Cardinals in 1947. Saigh said the Cards would play out their lease at Sportsman’s Park and then pick up a 10-year option. But the relationship between the Browns and Cardinals, never the friendliest, turned downright rancorous as lawsuits flew over maintenance of the aging and, frankly, decrepit stadium.

It wouldn’t be too long before the Browns had a new owner as well, one who was determined to run the Cardinals out of town. And Bill Veeck sure gave it his best shot.

Bill Veeck was a chain-smoker, a smart-ass, an egalitarian, and an iconoclast. He was also smarter about baseball than anyone wanted to give him credit for.

Veeck discovered that he could write off players as depreciable assets. He, like Rickey, saw the value in Negro League players (but unlike Rickey, he was willing to pay Negro League teams to buy their contracts) and started scouting Mexico and the Caribbean for talent. As owner of the Indians from 1946 to '49, his promotions had drawn millions to cavernous Cleveland Stadium, but he ended up having to sell that club to pay for his divorce. In 1951, when the chance came up to buy the Browns, he jumped at it.

Veeck, who never met a stuffed shirt he didn’t want to unstarch, took the fight right to the Cardinals. He hired former Redbird Rogers Hornsby to manage. The marriage was a brief and unhappy one: Hornsby was totally humorless and more than a little racist, and Veeck fired him midway through the 1952 season. The players sent Veeck a trophy, calling it “the greatest play since the Emancipation Proclamation.”

When the Cardinals fired manager Marty Marion, the Browns grabbed him too. And Veeck was happy to reunite with pitcher Satchel Paige, who had done wonders for him in Cleveland.

But he became best known for his stunts. In an early game, he announced that drinks were free, and personally passed out beer in the stands. He had a “Grandstand Manager” night, when a section of the fans in attendance were polled for strategic moves. His most notable gimmick came on August 19, 1951, when he sent Eddie Gaedel, all 3-foot-7 of him, up as a pinch-hitter. With no discernible strike zone, Gaedel walked on four straight pitches. Veeck joked later that he'd told Gaedel not to swing under threat of death from a rooftop sniper.

Attendance was trending upward for the Browns and, more importantly, downward for the Cardinals, who entered a relatively fallow period during the National League ascendancy of Rickey’s Dodgers. The Cardinals' worst problems came away from the field: In 1953, Saigh, the owner, was convicted of income tax evasion and given a month to sell the team.

Saigh fielded multiple offers from out-of-town interests, including groups in Houston and Milwaukee, and even one that considered moving the team to Detroit (that prospective owner was Harry Wismer, who would go on to be one of the “Foolish Club” of original AFL owners in the 1960s; he owned the New York Titans, later the Jets). It looked like Veeck might have won the war over St. Louis. But just before the deadline, a new buyer stepped up: August Busch, scion of the Anheuser-Busch brewing family.

“I decided I had better get out of town back in 1952 after Gussie [August Busch] bought the Cardinals, because he was smarter, handsomer and he had better posture,” Veeck recalled in his Hustler’s Handbook. “He was also richer, wealthier and he had more money.”

Veeck knew he was licked, and sold Sportsman’s Park to Anheuser-Busch “for $1.1 million and all the repairs they could find,” he said. (Busch wanted to rename the ballpark Budweiser Stadium, but the league didn’t approve. So he named it Busch Stadium … and two years later, introduced a new beer, Busch Bavarian.)

Veeck first considered moving the Browns to Milwaukee, where he’d had success owning the minor-league Brewers—but the Braves had designs on that city, having realized by then that Boston, like St. Louis, no longer was a two-team town. With his pursuit of publicity and his willingness to fight over revenue-sharing from game broadcasts, Veeck hadn't made many friends or allies among the other American League owners; when he zeroed in on Baltimore next, that cohort, seeing a chance to be rid of him altogether, blocked the move. Veeck obliged them, putting the team up for sale. Like Saigh several years earlier, he fielded offers from a variety of groups, including minor-league cities with major-league aspirations like Kansas City, Montreal, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Eventually, every one of those cities got a major-league team.

Ultimately, Veeck sold his stake in the club to his fellow Browns owners, after which the league pretty much immediately granted the Baltimore move. “I didn’t leave baseball graciously,” said Veeck, who later ended up owning the White Sox for two separate stints. “I was evicted.”

With that, the Cardinals had St. Louis all to themselves. They've ruled the roost ever since.