On Monday, at around 10:30 a.m., Slate courts and law reporter Mark Joseph Stern tweeted a link to a document concerning an upcoming Supreme Court case. In a reply to his tweet, another journalist asked him about how he found it. A very bleakly familiar type of hell broke loose.

A new case on the Supreme Court's shadow docket: Yeshiva University wants the justices to halt a lower court order that required it to approve an official LGBTQ student club.

— Mark Joseph Stern (@mjs_DC) August 29, 2022

I foresee a 6–3 order in Yeshiva's favor. https://t.co/TuZ42C4Q2I

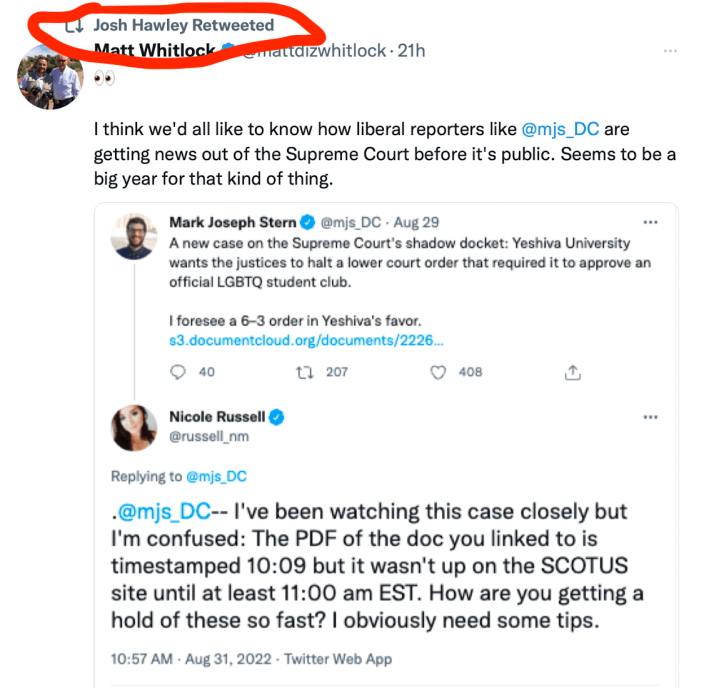

Stern, as the whirring right-wing outrage machine now has it, has unwittingly revealed a conspiracy to leak Supreme Court information to liberal journalists, and possibly has unmasked himself as the source of May's leak of the draft majority opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, which overturned the right to abortion access in the United States.

That's a lot to insinuate from one tweet. Here's what actually happened.

The Supreme Court has a Public Information Office (PIO). The PIO has a procedure for keeping reporters informed about cases that are headed the court's way. It's called a "call-out list." A reporter can contact the PIO and say which case they're following. The PIO puts the reporter's contact information on the call-out list; then, when that case makes it to the court in the form of an application, the PIO notifies the reporter and sends along the relevant information. All of this is explained in plain language in the Reporter's Guide that anybody can get right off of the SCOTUS's website (emphasis added):

The Public Information Office maintains a list of press names, email addresses and phone numbers. We suggest that press who wish to be included on a "call-out" list for a specific application touch base with the Public Information Office. "Call-out" is provided by the Public Information Office on a limited basis, usually upon request by a member of the press. If you are following a particular application, you may alert the public affairs specialist and ask to be called when it has been decided. Similarly, if you are aware of an application likely to be filed with the Court, we will be happy to notify you when the papers are filed.

The Supreme Court

If you have worked in or in concert with any U.S. federal government department or agency in your whole life—or, I dunno, ever tried to get Medicaid, or listened to a few minutes of any lame drive-time radio DJ's dusty shtick in the past 50 years—then you will not be surprised to learn that the Supreme Court is a big and byzantine institution with lots of janky parts that do not always smoothly synchronize their movements. The parts that do the judicial stuff are not the parts that maintain the email lists, and the parts that maintain the email lists are not the parts that update the website. Thus, it is possible for the reporters on the PIO's call-out list to receive their notice of a court application or decision before news about it has gone up on the SCOTUS website, where a layperson could find it.

Even if you didn't previously know that, prior to reading the above paragraph, very likely its slight bureaucratic awkwardness strikes you as familiar, like finding out that a given person has lungs. Absent any reason to think otherwise, I guess I probably would have taken for granted he had lungs. Still, maybe you would wonder about the specifics of it, particularly if you were another journalist who wants to cover this Supreme Court case but had not previously heard of the call-out list: How did Slate's courts reporter get this document in time to tweet out a link to it, apparently before the document appeared on the SCOTUS website?

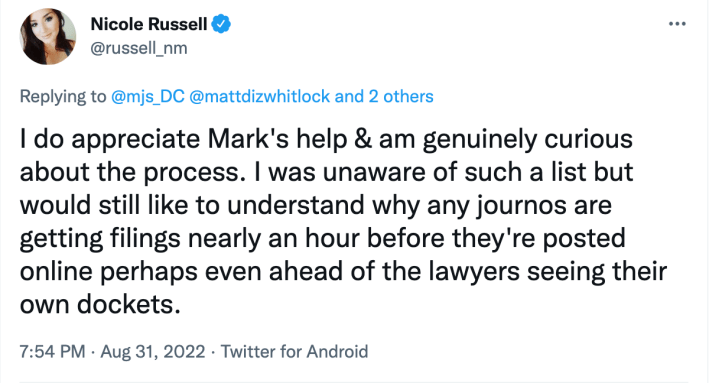

One such person who wondered this was Nicole Russell, who writes for the conservative Washington Examiner and the bonkers right-wing Daily Signal. So she asked Stern, on Twitter, in the performative Columbo for Dummies mode common to oh so dismally many just asking questions routines online:

.@mjs_DC-- I've been watching this case closely but I'm confused: The PDF of the doc you linked to is timestamped 10:09 but it wasn't up on the SCOTUS site until at least 11:00 am EST. How are you getting a hold of these so fast? I obviously need some tips.

— Nicole Russell (@russell_nm) August 31, 2022

My friends, I come not to gawk at this poor dude's hideous misfortune, but to educate. This is a service type of blog. What I would like to note here is that from the moment Russell clicked the button to post her reply about the PDF's timestamp, Stern was fucked no matter what. To whatever extent Russell intended her question as an earnest attempt at learning the clunky press operations of the Supreme Court, it also doubled as the ignition for an engine that has absolutely no use whatsoever for that question's anodyne answer.

One of the most malignant features of Twitter and the broader 21st-century media ecosystem is the deranged quantum branching they allow, and the power they grant to those who benefit from that branching. This is a perfect example. Each bad-faith quote-tweet and screenshot of Stern's initial tweet and Russell's question is the seed of a paranoid pocket universe in which Stern never answered; in which the unexplained mystery of a liberal blogger at liberal Slate having access to a Supreme Court document not yet made public serves in turn as the resolution to the greater mystery of how the Dobbs draft opinion leaked—itself a fake controversy the right seized on as a distraction from the wild unpopularity of the opinion itself and the damage it appears to have done to Republican midterm election ambitions.

For each of those quote-tweeters and screenshotters, the goal emphatically is not to get to the bottom of this minor and easily resolvable case, but very specifically to obscure that bottom: to ensure that those paranoid pocket universes outnumber dull reality 100,000-to-1. So that only those actively looking to exonerate Stern of participation in a vast liberal conspiracy could ever hope to find his very simple and dumb exoneration; so that those who do not want to find it, who prefer the curated unreality, will never have to accidentally stumble across a link to the Reporter's Guide to Applications Pending Before the Supreme Court of the United States.

As it happens, Stern contacted Russell via private direct message, on Twitter, to give her the heads-up about the PIO and the call-out list, and furnish her with the PIO's email address.

Here's what I DMed Nicole. I'm sure she and I disagree on many important issues, but I am always eager to help journalists navigate the Supreme Court's strange press rules. Now @mattdizwhitlock is fomenting a conspiracy theory that I leaked Dobbs. This is just pathetic. pic.twitter.com/UUm0s7m9J0

— Mark Joseph Stern (@mjs_DC) August 31, 2022

If he was acting on a vain hope that Russell really did just want to know how to get documents earlier and do her job better, it's hard to find too much fault with that. He was wrong—

—but still. You can sympathize with the hope that being open and helpful might have resolved things quickly. Because pretty much every single other possibility leads right here:

That's Missouri Senator Josh Hawley, a man notably experienced in riling up violent, psychotic reactionaries over phony conspiracies and then scurrying away, retweeting a coy bit of just asking questions from Republican communications ghoul Matt Whitlock. Hawley passes along to his nearly one million Twitter followers the implication that a Slate blogger might very well be the Dobbs leaker. Ignore that this would mean some SCOTUS source leaked it to Stern, who then didn't publish it but instead handed it to competing outlet Politico for the exclusive. We can't take down all this red string off the corkboard now.

If these people were acting in anything even vaguely resembling good faith, this could be hilarious and incredibly embarrassing. Hawley literally works in the Senate. Who the fuck knows what Whitlock does apart from shit-stirring on Twitter, but he certainly has been in politics long enough to have worked for the National Republican Senatorial Committee and former Senator Orrin Hatch. Either of these men, motivated by actual curiosity, could learn within minutes how it came to be that Stern tweeted out a document before it appeared on the SCOTUS website, but of course they are not motivated by curiosity, or even real suspicion, and they do not want to learn that. They want not to learn that, in fact; they want as many people as possible not to learn it.

Instead of this being a funny self-own by some right-wing scumbags with itchy retweet fingers, it's something darker and more frightening. Given the way things are now, Stern may well have good reason to fear for his safety: Even Hawley is afraid of the people who believe him.

So, what should Stern have done? DMing Russell did not prove to be the right move. Ignoring her wouldn't do either. That's a meatball for these freaks. Why isn't he talking? What's he hiding? An open and helpful public reply might have been the better move, but it takes longer to type a reply than to crop it out of a screenshot of her question and send it into the bullshit hurricane.

However Stern chose to respond, the crucial fact is this: The specifics of the Yeshiva University v. YU Pride Alliance SCOTUS application are not nearly as interesting or newsworthy to the bad actors on the right as the storm of paranoia and grievance that can be whipped up out of pretending to find something suspicious in the liberal media's handling of it. Everybody else, all those with sincere (if deranged) interest in the non-mystery of how the Republican-dominated court will handle this culture war case, can wait for the blog-length analysis from the knowledgeable courts and law reporter. Stern did nothing wrong, and yet the thing to do was not to tweet it at all.