Yep, that's me. You're probably wondering how I got myself into this situation. There I was, simply vibing and minding my own business in the transparent plastic cube where I spend most of my days, when suddenly everything went horribly, horribly wrong. It felt like flames, flames inside of my mouth, the most terrible pain known to frog. Perhaps I needed to make better decisions. Or, perhaps, the circumstances leading to my specific and most undesirable injury—being stung inside the mouth with the genital spines of a wasp—occurred due to factors entirely outside my control, the more powerful species dictating life on Earth, or the twisted vicissitudes of fate itself.

I spent my tadpole days in the the grasslands surrounding the paddy fields of Honshu, the largest island of Japan. Life was good there—cool waters teeming with insects that I could shove inside my mouth and swallow whole with the help of my eyeballs. The halcyon days of youth, when I had a tail! I remember them well! Everything changed when I was scooped up and taken to a laboratory inside the minimalist plastic cube that is now my home. It is no paddy field, but at least now I have a steady diet of mealworms and no longer fear American bullfrogs eating me alive. Those American bullfrogs have no morals, no sense of amphibious community. A frog eating another frog: Is there no justice in the world?

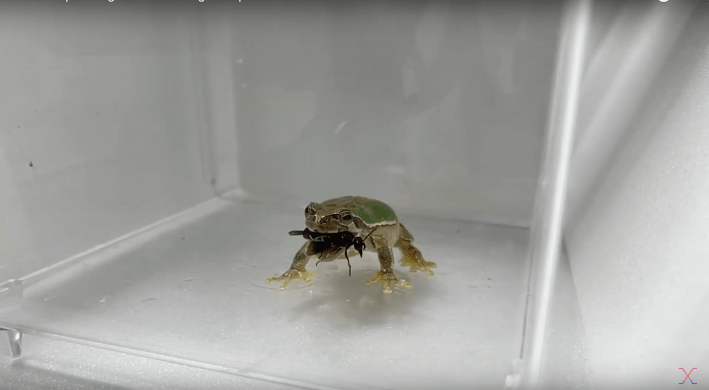

Then one day in my plastic container, there were no mealworms. There was only a giant black insect—a mason wasp, Anterhynchium gibbifrons. Of course, I did not know this. I only understood bug and not-bug, worm and not-worm. And I understood I was hungry. So I stuck my tongue out and snatched up that wasp right into my mouth. The wasp was to be my meal, the first in a day. The wasp was to nourish me, blessed fruit of the Earth, one life given to sustain another. Umami!

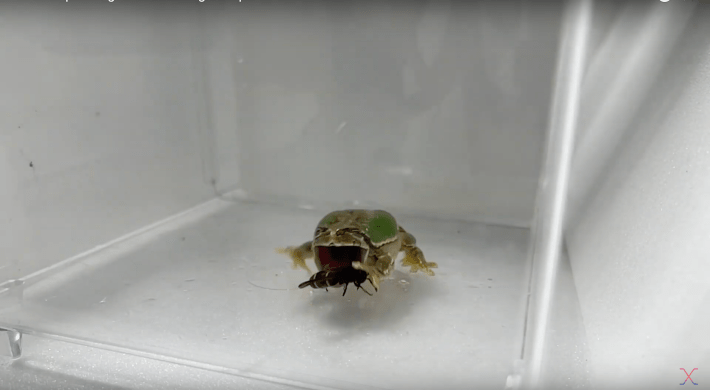

But then I felt a most awful sting, my tongue pierced by two spines extruding from the accursed male wasp's genitalia. The flames, the flames! O, fate! O, the mealworm gods of the plastic cage had forsaken me! Two daggers in my tongue; the wasp had stung and I could not free myself from his penis.

O, ow! O owieee!

Out, out, cursèd wasp!

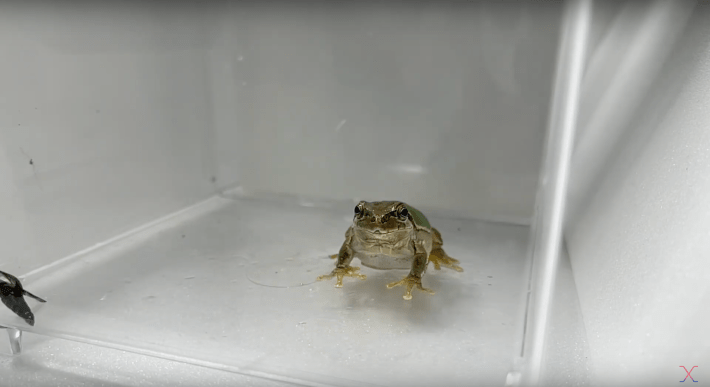

After an excruciating amount of time, I finally managed to free my tongue, and, by extension, myself. I watched the wasp, seemingly unharmed and in good spirits. Had we not lived through the same experience? What did the wasp make of all of this? Would the wasp ever leave this plastic cube? Would I?

As the wasp waddled away, penis spines and all, I found I bore no anger or resentment toward my former adversary. It is not the wasp's fault to have genital spines. We, predator and prey, are caught in a twisted evolutionary battle with no truce in sight. My right to eat does not supersede the wasp's right to live. My hunger does not countermand his penis. A wasp will do whatever a wasp must to make it out alive. And then, in a shadow of a reflection on a wall of my plastic cube, a glimmer of understanding, a scent memory of mealworms. I looked up.

Who could I trust? Maybe the wasp and I were more alike than I imagined, brought together by reasons beyond our ken. Maybe my greatest foe was, in fact, my closest ally. Just the two of us in this plastic cube, awaiting some strange future. What would become of us?