There's a common myth about the origin of the marathon that you've probably heard at some point in your life. In ancient Greece, during a war between the Persians and Greeks, a courier named Pheidippides is said to have run 26 miles from the town of Marathon to the city of Athens in order to send the message that the Greeks have won a battle. Then Pheidippides dies, presumably from exhaustion or something.

The truth of this story, as epic as it sounds, is disputed. If you carefully read through classical archives, you'll learn that Pheidippides didn't die after his run. In fact, he likely didn't deliver any sort of message of victory at all and was nowhere near Marathon. Instead, records have Pheidippides running a much more impressive distance. The man ran from Athens to Sparta, around 150 miles in two days, just to rally troops from the Spartans. There, he discovers that all those miles were for nothing—the Spartans are too busy with a festival and won't be able to send backup for the Athenians in time. And thus Pheidippides begins his journey back to Athens, rounding up his journey to roughly 300 miles.

Last week I watched something of a modern-day Pheidippides loop around Central Park. I entered the park from the entrance near Columbus Circle and followed the map on my phone to a specific set of coordinates—precisely 40°46'05.3" north latitude and 73°58'45.2" west longitude. It was the location that Kenny Moll, a rising senior at Fordham University, had sent me the night before for his aid station, the spot where spectators could meet up with him and where runners in his group could refuel and rehydrate.

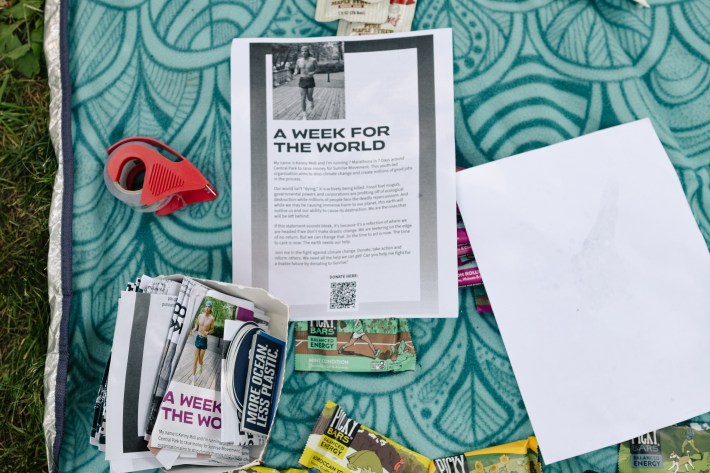

I arrived at the aid station at 9:02 a.m., just in time to catch Moll on a brief break before his fourth lap of the six-mile Central Park loop for the morning. He was all smiles as he shook my hand, apologizing for how sweaty he was. Around me, the aid station was filled with movement. Michael-Luca Natt, Moll's friend and an acquaintance of mine, cracked open a can of cold water and poured it over his head. A picnic blanket was laid out in front of a tree, littered with packets of maple syrup, performance bars, and zines with explainers on climate justice. At the front was a bike with a banner strapped to it: "7 marathons, 7 days, to fight climate change."

I had discovered Moll's project on Instagram the previous Wednesday afternoon. He had pledged to run seven marathons in seven days in order to bring more awareness to climate change and raise money for the youth climate organization Sunrise Movement. The idea had sounded so physically taxing that I had to see it for myself. Moll was running all seven marathons in Central Park, which made it easy for me to spectate in a way that caused little trauma for my own body.

By the time I showed up on Friday morning, Moll had already racked up roughly 149 miles for the project that week, almost equivalent to the distance Pheidippides had traveled to Sparta. Running at a nine-minute pace, Moll was completing roughly four six-mile laps around the park each morning, starting early at 6 a.m. and finishing around 10:30 a.m. Almost as soon as I got there, the break ended. Moll stood by the curb and ushered the rest of the runners, a pack of roughly 10 people, back on to the road. Then, they took off again to finish the last eight miles of Moll's morning run.

At Fordham, Moll is an environmental studies major and is no stranger to pushing the limits in the name of activism. Last September, he was arrested with over a hundred other people in a peaceful blockade of the Federal Reserve Bank, calling for an end to bank-funded fossil fuel financing. More recently, he was one of the 15 protestors detained at Fordham's pro-Palestine encampment. For Moll, there is a clear connection between running and activism.

"Running is inherently political," Moll tells me. He's just finished his sixth marathon of the week, and I've pulled him aside to ask him some questions. He explains to me that the type of running he engages with is a privilege made possible through things like access to healthcare, but also learning and acknowledging the subjugation of marginalized communities. During the day he made sure to emphasize that the ground he is running on here was built on the vibrant Black community of Seneca Village, which was ultimately destroyed to make room for Central Park.

With these marathons, Moll was hoping to introduce the running community to the other world he is a part of—the climate justice community. His partner, Jamilah Maronde, tends the aid station while he's off on his fourth lap around the park, and I watch as she speaks to passersby about the project. They promise to return for the panel of activists Moll is moderating after the marathon.

It's still early in the day, and packs of runners keep racing by. On one occasion, someone yells "Kenny!" as they run past the aid station. Maronde tells me that the regulars in the park, runners and cyclists alike, have begun to notice their project. Some have even started joining Moll for portions of his daily mileage.

There are three speakers for the post-marathon panel on Friday. The first is Dejah Powell, the Deputy Organizing Director for Sunrise Movement. She asks the members of the audience, "What initially piqued your interest, anxiety or fear about climate change?" Around me sit a mix of other runners and some local activists. I notice that two of the passersby have indeed returned to hear what the panel has to say.

Natt, an organizer with the New York City chapter of Sunrise Movement, who's fresh off running his fifth marathon of the week with Moll, speaks last. He has only skipped one day so far, and that's because he had a court summons in Delaware. He was arrested back in February with other activists after staging a sit-in at President Biden's campaign headquarters. "It's a beautiful Friday morning," Natt says. "There are plenty of people who are stuck in a nine-to-five, maybe they even have three jobs, and they're still struggling to pay rent ... And I think if all of us can afford to be here, we can afford to do a little bit more and to stand up for them."

I met Natt for the first time in the spring of 2023 in the basement of a school near Chinatown. I was at my second Sunrise Movement NYC meeting, and I distinctly remember him riding away on a skateboard after the meeting. It's funny how small the world of climate activists can seem sometimes, so I ask him how he met Moll. Turns out they've only known each other for a few months. After being connected by a mutual friend in March, the two ended up messaging. As Moll trained for the big event, he decided to invite Natt along.

"The miles went by so fast," Natt tells me. "He's so cause-oriented. I felt super inspired by his ability to organize this whole project." Like Moll, Natt has only started to run more seriously in the last year or so. As he began to dedicate more time to the sport—more recently running a 50-mile ultramarathon—Natt was struggling with the insular nature of the activity. “The idea of doing more athletic things for a cause was always something that was on my mind as soon as I started racking up miles," he says. "I don’t want to just be running just to run.”

Natt hadn’t gone into the week planning to run a marathon day. Unlike Moll, he wasn't intentionally training for it. “I just take it lap by lap, and every lap I’m like, ‘I can do one more.’’ He also hasn’t been able to truly rest after some of the runs. On a few of the days, Natt had to immediately head off to work in order to make it to a full day shift at his retail job. Even then, he still feels good about the last day ahead of him. “At this point, I feel like the whole thing tomorrow is kind of in the bag.”

Moll tells me something similar. Seeing the group of runners who have accompanied him grow over the last few days brings him the energy to power through, he tells me. He says he's experiencing a runner's high to a degree that he's never felt before. "I am so lucky and so fortunate that I have a bunch of sickos just like me, coming out, and doing this," he tells me. It gives him hope and optimism that more people might make an effort to stop climate change. I have to admit, my visit has filled me with enough excitement and curiosity that I tell him I'll be back tomorrow for marathon number seven.

The next day, I arrive around 8 a.m., just in time to watch Moll and his crew return from their second lap around the park. Charli XCX's "Von Dutch" is blaring from a speaker in a bike basket as they settle in around the aid station. The group is bigger today, roughly 20 people, and I'm told that a few of the runners are planning on finishing a marathon. Besides Natt, no one else has accompanied Moll the whole way thus far.

The scene is both festive and serene, intimate and joyful. It makes me think of the ways we talk about climate change and the anxiety it can induce in people. I don't blame those who shy away from activism. It can be intimidating. So often activism engages in uncomfortable and exhausting topics and the tactics which make the biggest splash in the news can seem extreme or daunting. As Moll tells me days later, reflecting after all seven marathons are done, risking arrest—like he has done multiple times—is certainly a privilege. It's one of the reasons why he began this project in the first place, to create a space where those who are less politically engaged could experience a tamer way to make a difference.

The group refuels, cracking open cans of water or gulping down packets of maple syrup for energy. I've never seen more Garmin watches concentrated in one location in my life, and I ran cross country in high school. There's even an enthusiastic cycler who has stopped by to congratulate Moll. Then, Moll and the others are off again, racing down the road to start the second half of the marathon, a few new participants in tow.

Other running groups are just getting started for the day, and closer to 9 a.m., a horde of runners cheer as they go by the aid station. At one point, I notice a father—presumably also a runner—pull up to the aid station with a stroller, baby strapped inside. Before I know it, Moll and the other runners are back, done with their third lap around the park. That's when I noticed the father with the stroller again, chatting with a few of the runners who are about to head out for the day. He opens a can of water, and the baby calmly sips from it. "Oh my god, did he just run with the baby?" I ask the person next to me.

I learn later that the man with the stroller is a regular at one of the running groups Moll is a part of. And yes, he and the others did run with the stroller all six miles around the park. It's a testament to the community Moll has built. At the aid station, I learn that one of the people who has decided to run the full marathon today is a 17-year-old boy named Case, who learned about the project through Instagram and has never run a marathon before. If all these random people can be inspired to run further than they ever have run before, who's to say they won't join a climate organization after this?

After running four six-mile laps around the park, Moll runs a smaller two-mile loop in order to hit that magical number of 26.2 miles. When the group lines up at their start line, there's cheering all around. A cowbell rings and Moll takes off from the aid station for the last time. Two more climate activists have shown up to support the project line up at a finish line, grasping the ends of a gold ribbon. Just 14 minutes later, the runners have returned, a victorious energy in the air. Moll is leading the pack, and Natt is right behind him. They tear through the ribbon, the marathons are finished.

There are so many hugs to go around in the minutes after. The air smells sharply of sweat. When Moll and Natt embrace, I think about all the early mornings and endless miles they endured together. But even then, my mind drifts elsewhere. This world we live in is burning—there are floods tearing through South Florida and the heat waves in Delhi are incomprehensibly nightmarish. The entire East Coast of the United States has been a sweltering mess this last week. Cooling down can be a matter of life or death, but at the same time, who are we to be blasting our air conditioning or driving our cars when the cost of doing those things seems so apparent? At this point, what does it even mean to run through a park on a hot day where the air quality could endanger you?

Later, Moll tells me this wasn't the first time he has attempted this project. He tried it in his hometown of Chicago last year, but wasn't able to complete all seven marathons. Ironically enough, on day three, Moll woke up to air quality conditions caused by Canadian wildfires that made it dangerous to run.

Today, like the day before, Natt is the last to speak of all the panelists. At the end of his speech, he asks everyone to hold the hand of the person next to them. We all recite the same words, "I am strong. I am powerful. We are stronger together."

For people like Natt and Moll, humanity is now stuck in a war of our own creation, battling against rising temperatures and corporations willing to sacrifice our collective future for their own interests. It is a conflict that so often feels futile, but it turns out the human will can be indomitable. Millennia ago, Pheidippides raced the length of Greece, hoping to change the tide of a battle. I watched as Moll ran that worn path around Central Park, slowly but surely rallying troops to the cause.

On the road home, Pheidippides runs into Pan, god of the Wild, the story goes. The deity says that despite his loyalty to them, the Athenians have abandoned him. When the Greek runner pledges on behalf of his people to do better, it changes the tide of the battle. We'll never know what really happened: how far Pheidippides ran, what gods he encountered, whether he ever delivered a message to Marathon. But any way you read it, sometimes all it takes is one determined person—albeit someone with incredible stamina, strong legs and an insane amount of willpower—to make a difference for their community.

Disclosure: The author was involved with running Sunrise Movement's high school campaign programs for the year of 2023.