It took Jonni “Rotten” Ramirez one and a half seconds to ruin his life. I’ve watched the footage: Ramirez, real name Jonathan Carrion, is wrestling against Prince Adam for the Inspire A.D. promotion in Austin, Texas. The event is called “The Long Walk Home” and it’s just after 7:00 p.m. in the gray-beige back room of a pinball arcade in the far northwest side of town. They’re standing face-to-face on the top turnbuckle of a stiff gray ring, Carrion’s hands on Adam’s hips, flanked on one side by 200-something mostly attentive attendees.

Carrion jumps and wraps his knees around Adam’s neck and shoulders, the setup for a hurricanrana, and the two of them leap into a synchronized flip toward the center of the ring. Almost immediately Carrion is lying in the middle of the mat, shout-moaning, clutching his shattered knee. The two wrestlers crawl toward each other and quietly make a plan. Adam rolls Carrion up onto his back, protecting Carrion’s fucked-up knee, in a quick, awkward small package pin. Ding ding ding, goes the bell. Carrion writhes around the middle of the ring while the crowd mills about like goats, waiting for the next match. Carrion hasn’t walked on his own since.

That was in October 2022. Carrion’s out there somewhere, now, living on the streets around Dallas; barely mobile, in constant pain, and with over $30,000 in medical debt. Nobody can find him.

This is the gamble every wrestler makes: that someday he or she might be the one flat on their back watching the world collapse upon them. Everyone knows this. Everyone’s seen it. Nobody stops working.

You don’t see independent wrestlers on TV or in Madison Square Garden, not unless they get called up to the big time: WWE or AEW, or maybe the smaller corporate leagues, Ring of Honor or Impact. That phone call is something a lot of independent wrestlers dream about but few ever get.

Instead you see independent wrestlers in church rec centers and American Legions and old firehouses; shows with 10 people in a bar; shows with 200 people crammed into a small-town high-school gym. An excellent night might find 400 fans in a big-city brewpub chanting “THIS IS AWE-SOME (clap clap clap-clap-clap)” as the local champion duels a marquee-name out-of-towner. Those are “the indies”: local or regional wrestling promotions, worlds apart from the billionaires in New York or Jacksonville.

The wrestlers set up shop in the back of the venue, or outside, near where men with ponytails or unkempt beards or acne scars or social anxiety smoke cigarettes between matches, and sell their T-shirts. If they’re lucky, or popular, or if they do an especially good job in their match, they can sell a lot of T-shirts. After the show’s over and the ring has come down, they pick up the boxes of T-shirts and put them back in their cars. Sometimes the cars are held together with little more than crossed fingers. Then it’s back home, or someone’s couch maybe, until the next day, when they get back in the car and do it all over again a few hours away.

Data on independent wrestling is hard to come by. With no professional recordkeeping, any available information depends on voluntary fan submissions to open databases. Cagematch.net has ratings for 8,800 wrestlers who worked at least one match in the Americas last year, including those who worked on the major televised promotions, of whom 1,500 performed at least twice a month. Cagematch is missing a lot of data, though, and I estimate there are about 3,000–4,000 active independent wrestlers in America. The rest are some combination of touring foreigners and hobbyists: local talent, who work only every now and again, usually for just one promotion.

Independent wrestlers, the ones who make this a big part of their life, work hard. They work a lot harder than I do, certainly, and probably harder than you. Wrestling is their job, but it’s also their art. Wrestlers are driven to it by the same engine that powers writers or painters, though wrestlers are less likely to have wealthy parents paying their bills, and poets are less likely to end a performance covered in blood.

“There's no other form of entertainment where I can watch a person bleed in front of me. Not in theater, not in shows. Not in movies. Everywhere else you know it's fake,” said Georgia-based wrestler Effy. “ I've never blown up [gotten exhausted] in the ring while I'm bleeding. ... It lets a certain part of yourself out, where the adrenaline is so much higher. There's just no stopping you. It’s the only time I can stand in public and have people cheer me while I'm just soaked in my own blood.”

That blood is real. So is the pain. “Every time you hit the mat, it’s like a minor car crash,” Alicia told me. Alicia works out of Texas under the name VertVixen. For her and her partner, Adam (the same Prince Adam who was in the ring the night Jonathan Carrion was injured, and who now works under the name Lil Evil), wrestling is all-consuming: Work four or five days a week at a day job, pack a bag, then four nights on the road. She just got back from a tour of Japan and now she and Adam are back on the highway, criss-crossing Texas to work scores of promotions across the state.

Workers on a show within a few hours’ drive of home might get fifty bucks, maybe a big hundo. After doing their time on the bottom of the card, wrestlers who consistently get over with crowds and who build up enough of a presence through touring or social media can ask for $250 or $300 for a booking, with lodging maybe, even if that’s just the promoter’s couch and a cup of coffee in the morning.

“Wrestling never stops," said Kevin Cassidy. "The train keeps on moving. If you get off, there's no catching up—it’s nearly impossible. You just have to hope for the next train,” Cassidy, who works under the name Gentleman Jervis, has been off the grind until very recently: He didn’t work between February 2022 and mid-May 2023 while addressing some mental health issues. “The year I took off—it’s like I don’t exist anymore.”

“My motto was, ‘You don't work, you don't eat,’” said Colt Cabana, a Chicago-based wrestler. (Like many wrestlers quoted in this piece, Cabana asked me to refer to him by his work name.) “For someone on the independents, it's all about being on every single show that you can. Something that was stuck in my head was, if I miss a couple of shows, then people will forget about me and stop wanting to book me.”

Cabana is a 20–year veteran who has, by every measure, “made it” as an independent wrestler. He has a list of championship belts a mile long, a couple years in the WWE system, a long run in Ring of Honor, and a very popular podcast, The Art of Wrestling, likely the single biggest repository of wrestlers’ “shoot” (out of character) interviews. But his punishing schedule and total dedication to the game are standard for the industry, from the most successful main-eventers to the people wrestling the “dark” matches before shows start.

“I was on the road 200 days a year up until the pandemic,” said Cabana. “My body hurts all the time. Everything hurts. I guess a lot of me thought, like, ‘Yeah, I know, I'll feel the consequences when I'm older. But I'm willing to sacrifice that, to live out my dream and to have the greatest days of my life.’”

Wrestlers are, and I say this lovingly, weirdos: itinerant warrior-monks with minor personality disorders; flamboyant, charming creatures of bravado, with just enough body dysmorphia to make them gym freaks. Almost by definition one must be more than slightly eccentric to commit to such a punishing life-path. The absurd physical fortitude required to perform as a wrestler—and it is tremendous; I’ve heard of wrestling schools making trainees perform hundreds of air squats before practice—is matched only by the unyielding hustle necessary for career survival.

The furious war against the dying light is not, generally, a competition between wrestlers. Yet there are no formal structures within which wrestlers support each other; no pension funds or guild health plans. Mechanisms of wrestler solidarity are social and are formed nearly entirely by the bonds developed through in-ring work. Wrestling matches are spectacular acts of teamwork; athletic dances loosely choreographed backstage that evolve organically during their execution. While some wrestlers work “stiffer” than others, the most unforgivable sin a worker can commit is intentionally hurting their partner. To injure a wrestler is to throw them into existential jeopardy. When Dusty Rhodes cut his legendary “hard times” promo, considered one of the greatest pieces of mic work of all time, he drew a parallel between the crisis of factory workers displaced by automation and wrestlers injured in the ring: Neither could feed their families anymore.

“Wrestling pays absolutely nothing, unless you're part of the top five percent of people doing it and are assigned to a big company," said California luchador and stuntman Super Panda. "It's impossible to make a living just out of professional wrestling.” Wrestlers are freelancers, 1099ers, powerslamming ronin. There are no paid vacations and there is no retirement plan.

Independent promoters do not—cannot, in nearly every case—pay workers a livable wage. Many wrestlers depend largely on out-of-the-ring hustles in order to pay the bills. “‘Luigi Primo,’ to an extent, is a T-shirt company,” said Austin-based Italian pizza chef–themed wrestler and viral sensation Luigi Primo, who, full disclosure, is my close friend. “Merch, and especially shirts, that's like, half to two-thirds of the money. T-shirts are one of the last real products. There's T-shirts. There's video games. And there's delivery services. Those are the last three things that people want in 2023.”

“If I'm ever broke, or if I'm ever like, ‘Oh, I'm gonna need extra money for this,’ I'll just, like, bang out a new shirt design or a new sticker, throw it up on Twitter,” said CPA, a wrestler out of New York who works an accountant-themed gimmick. “If a handful of people buy it, it’ll float me for the next few days until actual money comes my way.”

All options are on the table for a wrestler trying to survive. “I bump and then I also have a podcast that I make money on. I stream on Twitch every week showing wrestling or video games. I'm doing Cameos,” said Effy, whose name is an acronym for “Electric Fantastic Fuck You” and who decided to become a wrestler during an acid trip a decade ago. Effy is surely the “it boy” of independent wrestling in 2023. His “Big Gay Brunch,” an occasional indie showcase of queer and trans wrestlers, has become a hit over the past three years. “I do merch. I'd say merch is probably 40 percent of my money.”

Independent wrestlers' dependence on direct fan support means wrestling fans have a unique relationship with performers. Watching someone wreck their body for your approval, underneath the gimmick, is a deeply intimate act: The wrestler literally cuts himself or herself open in the hope that you’ll help them buy groceries. It is this rare performance of completely consensual violence that compels the fan to want more, beyond the ring. There is a desire to observe the wrestler in their “natural environment,” away from the spectacle and pretense of kayfabe; to possess the wrestler as a superhero and a whole person simultaneously. But this desire for authenticity is conditional: The wrestler must perform as a “character out of character” in order to facilitate the patronage upon which they depend. Fans don’t want to see the Effy who shits and feels sad and hates getting his blood tested; they want to see their friend Effy, the one who winks and plays video games and talks about “the business.”

The wrestler is a product, inside and out of the body, inside and out of the ring. “Selling your body by the ounce is another viable option for performers. I suppose it's always been throughout the ages,” said Luigi Primo. What do you mean by that? “Just like, you know, violence. Oh, God, giving, giving and receiving violence.”

Someone with their head in the game and heart in the ring has a few natural predators: illness and injury, the major betrayals of the body. And the unnatural predators of the American independent wrestler are the rent check and the American healthcare system.

Wrestlers don’t like doctors’ offices. The doctor is the person who tells a wrestler they can’t work and then hands them a bill they can’t afford. This repulsion is an industry-wide pathology: Wrestlers frequently described to me the lengths they would go to in order to avoid having to go to a doctor. “A guy broke his nose at a show in New Mexico, so they put two pencils up his nose and adjusted it ‘til it was straight,” said Canadian wrestler and MMA fighter Mitch Clarke. The people I interviewed laid out a diorama of backstage folk medicine: wrestlers popping each other’s dislocated shoulders back into place; local tattoo artists, friends or friends-of-friends, draining wounds after a show; coalitions of hardened and well-intentioned people taping, gluing, and stitching each other together.

“What was the last time I went to the ER because of wrestling?” Adam asked his partner.

“I think it was when you busted your head open,” Alicia answered. "The first time you said, ‘I love you.’”

“Yeah. Four years ago. And that was because I I had a gaping wound in my head. Some of the boys in the back were like, ‘I think we just got to glue it.’ And they looked around at each other and they're like, 'Yeah, I think that's what we do, we glue it.’ So they crudely superglued my head back together.”

“You have this gauge, you have this sort of barometer of injuries," said Cassidy. "What's a one and what's a 10? You don't go to the doctor for less than an eight or maybe even a nine.”

“The emergency room is more or less forbidden unless you're at a risk of dying,” Luigi Primo said.

Much of the hesitation to seek medical care comes from the abysmal status of American health insurance. Wrestlers’ insurance comes in three flavors: Medicaid, ACA individual market insurance, or employer-sponsored insurance, whether from their day jobs or their partners or parents. None are great. Being uninsured is worst of all. (It’s worth noting that going to a hospital without insurance means you get billed more: Hospitals might charge someone with insurance $3,000 and someone without insurance $6,000, or more, for the exact same fucking procedure.)

Many wrestlers I talked to are on Medicaid or are uninsured, particularly if they live in a state such as Texas, with extremely restrictive Medicaid eligibility. Because Medicaid programs are designed and operated by the states, experiences with public insurance vary.

“I've been very lucky with healthcare stuff," said New York-based ROH wrestler Hot Sauce, who has avoided major injury so far in his career. "I've been fortunate to be on good New York City plans, where emergency room visits are covered. If they try to hit you with a bill for some out-of-state thing, [Medicaid] usually takes care of it. So I've been very lucky with that.”

Super Panda, who has had two major injuries while covered by Medicaid, had a worse experience. “With Medi-Cal [California’s Medicaid program], you're getting poor service, but you're getting service and you're not in debt. And then in something like Texas, there's zero healthcare, so you're just in debt. So it's all bad. And then the third option is to pay tons of money. Your options are bad service that's free; paying for service and being in debt; or crazy expensive service that you can't afford. Pick one. Congratulations.”

The Affordable Care Act created a private insurance market for people who don’t get insurance through their work, a category into which most wrestlers fall. In 2023, people with benchmark ACA insurance plans would need to spend over $10,000 before their insurers start pitching in on their healthcare costs.

“I got staples put in my head,” said Cabana. “I remember going downtown in Chicago, where I lived, to RUSH Hospital, because I didn't know where to go or what to do. Looking back—there's so many looking backs, you know, you should have just gone to emergency care, whatever—I think it was $500 to take my stitches out. I think I made $150 for that match.

“I went to get an MRI on my left shoulder. I asked my insurance, who can I go to get an MRI? They said, ‘Oh, you can go anywhere.’ So I went somewhere. And then I got the MRI, I get my insurance card, and they said that they don't take that insurance. And so that was a $5,000 bill. I’m just like, What am I paying $400 a fucking month for?”

On top of that, while ACA premiums are subsidized for people making under $54,000 a year (with subsidies getting very small on the higher end), those subsidies are based on income estimates. If a wrestler makes more than expected, they pay a big penalty. “State insurance is pretty horrible," said Super Panda. "Not having insurance is pretty horrible. Recently I started paying for insurance and I ended up getting fined on my taxes because I earned more money than I normally do. So they fined me and the IRS kept my entire tax return. People at H&R Block were impressed by how much they screwed me over.”

This whole thing—unaffordable premiums, insane deductibles, tax penalties, the works—smells rancid to someone with a wrestler’s nose. Wrestling, an art forged in grift and sideshow, is a deeply paranoid trade, and wrestlers are at all times afraid of being on the wrong end of a hustle. It is terrifying to a wrestler to wake up and realize they’re the one left holding the bag.

“The doctor telling me he needs me to pay $40 per pill of Advil? That's a fucking work,” said Effy. “We don't want to get scammed. We feel dumb. The last thing a wrestler wants to feel is that they're getting the wool pulled over them, because that's what we do for a living.”

The American insurance model has real, harmful consequences for wrestlers, beyond the money. If someone is afraid of healthcare costs, they don’t seek healthcare. In 2021, one in 11 Americans reported that they delayed or refused medical care because of cost.

Chris Cruz, a Texas-based wrestler who also works as a nurse, told me, “There's plenty of people that I speak to who are like, ‘Man, I've been ill, I've been hurting for so many days, and I didn't want to come because I couldn't afford the bill.’

“I have family members bring in patients who really should have called 911 with a completely dislocated ankle, foot, arm, something, or having some active stroke symptoms. And it’s ‘I'm afraid to call 911 because I can't afford it.’ It's the brutal reality of American healthcare, and it's very depressing,”

The tension between getting healthcare and going broke is awful even if you’re not taking a Canadian Backbreaker four days a week. For wrestlers, who have chosen a career in which they are injured constantly, the consequences are heightened, even mortal. ”Because I don't have insurance, I had plenty of injuries," Adam said. "There was a summer where I was … Well, I was addicted to pain pills. Like, I just couldn't function without it. If I had the resource of going to rehab, I definitely would have taken it. But I quit it cold turkey. It was hell for a little bit.”

“If you weren't in so much pain, because you were able to go to the friggin’ doctor, maybe you wouldn’t have started taking the pain pills,” Alicia said.

The traditional way to end a career in wrestling is to “go out on your back.” The final moment of a wrestler’s legacy is a three-count pin upon which another worker’s reputation is cemented, a torch successfully passed, the essential momentum of the business carried forward. Brock Lesnar, the sweatiest wrestler in the game, had been a marquee name (and real-life UFC champion) for over a decade by 2014, but when he pinned the Undertaker at Wrestlemania 30, breaking Taker’s 21-year undefeated record at the event, it was a business arrangement, making Lesnar a guaranteed draw for another decade. The wrestler’s ultimate job is to lose: In their defeat, the cycle of carnie samsara continues.

Too often the final defeat comes not by the hands of another wrestler, but by the sport itself.

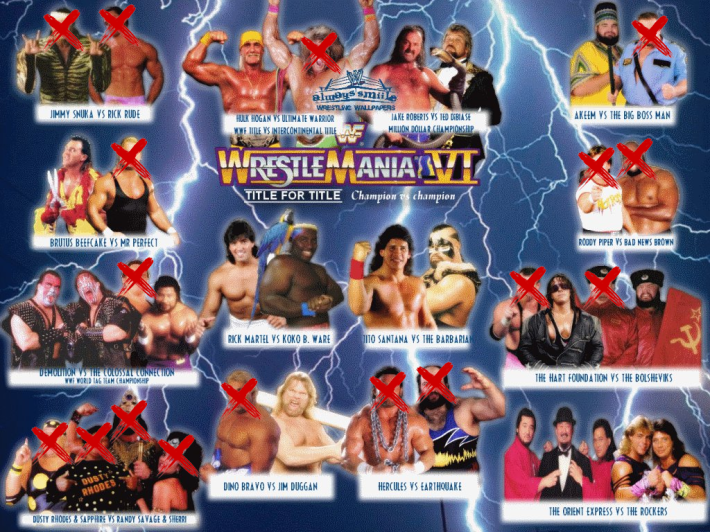

The Ultimate Warrior pinned Hulk Hogan in the main event of Wrestlemania VI, WWE’s flagship event of 1990. There were 36 workers on the card. Seventeen of them are dead. Their average age of death was 55. It’s a worse mortality rate than that of football players. Cataloging dead wrestlers could fill a book. It took me 54 seconds to scroll down Wikipedia’s list of notable wrestlers who died before age 65. A 2014 study found that male wrestlers aged 25–49 had a mortality rate 4.5 times that of the general population.

“This business has a hell of an entrance plan, but it’s got no exit plan,” said “Rowdy” Roddy Piper in a 2003 interview. “I’m not going to make it to 65.” Piper, who worked Wrestlemania VI, died in 2015 at age 61.

Wrestlers die in all kinds of ways. Cardiovascular disease, which took Eddie Guerrero, Brian Pillman, and my personal favorite wrestler of all time, Macho Man Randy Savage, is one of the most common. Overdose and suicide both happen more frequently among wrestlers as well. Chyna, who gave so much and always deserved better than she got, overdosed; all-time indie mic talent Larry Sweeney hung himself from a turnbuckle at age 30. Many wrestler deaths are related to steroids and drug use, the essential tools and coping mechanisms of the trade. Piper’s contemporary, “The Patriot” Del Wilkes, claimed he took over a hundred pain pills a day.

Most wrestlers don’t die young. But all of them wear battle scars. Each of the 13 wrestlers I spoke to for this story noted a persistent injury—a tweaked shoulder, a lingering concussion, a bad knee—the pain of which has become a persistent hum in the background of their nervous system.

“A few years ago, I blew out my shoulder, or my rotator cuff was torn, after a match with Warhorse,” Adam said. “I had to wrestle Super Crazy later that night, so we sent one of the green young guys out, get a roll of KT Tape. And I just KT Tape my whole shoulder and wrestle a no-ring lucha match with Super Crazy. It's not smart.”

“But that's what we were brought up to do," Alicia interjected. "If we don't wrestle, we don't get paid.”

“Yeah, I would have lost a lot of money.”

“So that's the reality of this,” Alicia said. “To get paid, you have to do the job. To do the job, you need to be physically in the ring.”

This pain is the admission fee, but it’s not the only expense—far from it. This is America, after all. Twenty-three million Americans have medical debt of over $1,000. That’s on the low end for the wrestlers I spoke to who have unpaid medical bills. And nearly all of them, current debt or not, cite lifetime sums in the tens of thousands.

“I went to the ER and [they said], ‘You got to pay your deductible,’ and then I ended up maxing out a credit card,” Cassidy recalled.

“I don't remember [exactly] how much my concussion visit took," CPA said. "But between the ambulance and the overnight stay in the hospital and everything else, probably like $12,000 just for that alone. I was paying $50 or $100 a month for a long time. I fell behind with other bills. And I just couldn't really afford to pay it every month.

“It wasn't like I couldn't afford the $50 every month, but I had gotten laid off from a job the day before I moved into an apartment and I couldn't find another full-time job for like a month or a month and a half, so I was just doing Instacart and Uber Eats, stuff like that. It wasn't really steady. I think around that point, I just stopped paying and my general financial being kind of collapsed for a few years.”

“I’ve spent something like $8,000, maybe somewhere between $5,000 and $8,000. It's hard for me to remember,” said Luigi Primo. “I feel like it's pretty low, though, compared to what some people have. I'm trying to pay them, and I think I've paid them all, but I need to go back and check. But it's not for lack of trying.”

Debt has a way of wriggling into your brain and vibrating at a high frequency. People who have trouble paying healthcare bills report dramatically higher rates of mental health issues and are found to have poorer health outcomes in general. “I owe probably upwards of 30 grand, last I checked," Adam said. "It makes me feel like a fucking loser. I just like—I want to go through like a process of actually paying it off, but every time that I go through that, something in life happens where that money needs to go first. It's one of those things where it's out of sight, out of mind, you know, because if I sat down and had an existential crisis about it, I think I'd be like, What the fuck am I going to do?”

It doesn’t have to be this way. To American wrestlers, avoiding medical care because you’re afraid of healthcare costs is an obvious decision, a total “Yeah, duh” from everyone I talked to. But this is a distinctly American pathology.

“That’s a crazy concept to me,” said Mitch Clarke, a Canadian wrestler. “I mean, no offense [again, he’s Canadian], but I’ve never experienced it.”

Canada has a tremendous history of professional wrestling, from days-of-yore black-and-white-photograph legends like Stu Hart and Killer Kowalski to more modern superstars like Kenny Omega, sleeper GOAT Chris Jericho, and WWE’s Kevin Owens and Sami Zayn, both former indie icons. And Canadian wrestlers know not to fuck with American healthcare.

“One [fellow Canadian] on a show dislocated his shoulder,” said Clarke. “And he waited—basically, they drove back over the border that night in order to go to the hospital.”

LuFisto is a Quebecois wrestler whose spot in the pantheon of independent wrestling is already secured. She started in the business back in 1997 and since then has been at the vanguard of Western women’s wrestling—specifically, hardcore, intergender, and intergender hardcore wrestling. She once picked up a man (Nick Gage, who later became a real-life bank robber and allegedly died for seven minutes in an ambulance helicopter, and who is held in high esteem by people who work with him) and threw him into a pane of sugar glass shortly before being speared into a net of barbed wire. Hers has been a career of insane perseverance and triumph over a litany of injuries and illnesses—a back injury, a heart defect, an exploded patella and arthrosis of the knee—that would take out basically anyone other than the most intense wrestlers, much less civilians.

LuFisto was diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2018 while living in the United States. “Because I was a resident and not a citizen, the biopsy and the blood tests and everything cost me over $10,000,” she said. “I was trying to find insurance and the cheapest was $800–$1,000 per month. I'm like, ‘OK, how am I supposed to pay my rent? I'm not working for WWE!’

“They wanted me to see an oncologist. When I tried calling around I was told, ‘Oh, you're an immigrant, we can’t help you.’ Some people even hung up on me. I remember saying to a woman, ‘What do I do? You’re telling me I have cancer?’ and she just said, ‘Well, I’m sorry.’”

Ineligible for Canadian healthcare by residency requirements, LuFisto ended up needing to take out a loan from a Canadian bank to cover her costs and found a Planned Parenthood that would provide affordable surgery. Three months later, a doctor found that some precancerous cells had returned. So she left the States.

“That's why I went from being a United States resident to coming back to my own country—because I couldn't deal with that healthcare system,” LuFisto said. “I'm staying in Canada. I live here, and I will travel to wrestle, because I don't want to have your guys' healthcare system ever again. I always make a bad joke, but it describes what the American system is. If you have a heart attack, and they take care of you, and you're fine … you're gonna have another one when you get the bill!”

She contrasted her cancer care with her knee injury in 2019, which was treated in Canada. “I had just come back [from the U.S.]. As soon as I got to the emergency room, I literally waited 10 hours. But once I waited those 10 hours, I got in, they had me going through X-rays, I saw an orthopedist, I was taken care of. And all this only cost me like $1,000 for everything. And as soon as I got coverage on the system [after satisfying Canadian Medicare’s residency requirements], they reimbursed the $1,000.”

It’s true that Canadians wait longer for specialist care than comparable countries, and it’s true that wait times in Canadian ERs can be extremely long. Much of the blame for this can be found in the government’s continual austerity project. But Canadian healthcare is allocated by medical need.

“It's all about priorities,” LuFisto allowed. "You go to the emergency and you can't breathe for some reason, they're gonna see you right away. If you're just coughing, you're gonna wait longer. My patella had exploded in four pieces. So as soon as I got to see the doctor, he sent me to get an X-ray. A few hours later, as soon as he saw what it looked like, he’s like, 'This is an emergency, we need to get that surgery ASAP.' The next day I was on the operating table.

“A lot of people here complain that it always takes longer to see a doctor here, but I always found that once you lose it, you know how precious it is.”

America, on the other hand, is an Eyes Wide Shut butcher-orgy of private market innovation. One recent development is crowdfunding: If you’re lucky, you can beg a bunch of online strangers for the chance to survive. Get past the initial revulsion at the fact that this is how we exercise basic human rights in the richest nation in the history of the world, and it plays on something genuinely touching: a distributed act of solidarity borne by all of us who are aware of our continual and arbitrary proximity to catastrophe.

“Fans want to help the people that they love watching,” said Inspire A.D. promoter Max Meehan. “I think there's a definite groundswell of compassion—that's one of the things that I think is really great about the veil between wrestling as this archaic secret society being lifted, to something that is understood as an art form. It's humanized the people in the business, and people, when they know somebody gets hurt, they are concerned. People know the difference between a work and a legitimate injury.”

And fans do show up to help. When "Mad Dogg" Matt Cross broke his leg doing a moonsault in Seattle in 2017, wrestling blogs begged readers to buy his merch. When indie cult favorite Danhausen broke his leg during a match, he turned to GoFundMe to pay his five-figure bills. But success does not automatically spare you from need, or fulfill the need you wind up with: In 2020, WWE Hall of Famer Koko B. Ware tried to fundraise $10,000 for a knee replacement, and couldn't. A casual search on wrestling news site 411Mania turns up 102 articles linking to wrestler or other wrestling-worker GoFundMe campaigns.

“In 2020 I had a full quadricep tear,” said Super Panda. "[Medi-Cal] covered it, but it took them a month to see me. I had to go for a [GoFundMe] campaign to be able to afford the MRI because they didn't want to see me until I got an MRI. … [The GoFundMe] was an idea from my friends. I didn't want to do it because I've never liked Kickstarter, because, you know, toxic masculinity. You feel embarrassed to ask someone for help. But this injury—eight months, I couldn't do stunts or wrestle. I was in a wheelchair. So my wrestling friends, they said, ‘No, we're going to start a GoFundMe for you.’ And they surprised me with it. The fans all got behind me and I was able to pay for the MRI and like six months worth of rent.”

What if the GoFundMe hadn’t worked?

“I'd be screwed. I would be behind on my rent. Luckily, everyone was behind on their rent during the pandemic. But I'd have to—my parents are poor. So I would either be homeless or severely in debt.”

But what happens when the GoFundMe doesn’t work?

Jonathan Carrion, the wrestler who shattered his knee in the back of a pinball arcade, was trying to gin up a comeback when he entered the ring for the show that destroyed his life. He had a lot riding on his match.

Carrion had been one of the first wrestlers in Ring of Honor when it started in 2000, working under the name Deranged. He was a child then, about 16. Carrion was never a main eventer, but he was someone you’d see if you stayed up late enough at night watching old matches on YouTube. With distance, his work has been celebrated by real wrestling heads.

He stayed in New York, working for ROH and Jersey All Pro Wrestling for about five or six years, and then became a journeyman on the indies in the tri-state area. With the exception of a few weeks in Ontario, Cagematch.net doesn’t show him leaving the eastern seaboard at all until late 2021, when he showed up in Dallas, worked a few shows, and went dark.

“Jonni had been retired from pro wrestling for quite some time,” said Meehan, the promoter of the show. “He was just getting back into the business.”

Carrion had been homeless for a couple of years at that point, crashing with people he met for a few weeks or months at a time, living in his car in between. He tried a shelter, but dropped out. He didn’t like the rules. Not that it matters, but he wasn’t drinking and wasn’t using hard drugs. He was just a guy who had been on TV once and for whom life lately wasn’t working out. He was uninsured, of course. About one in five Texans are uninsured.

Listen: It’s absolutely critical that you understand that this is a no-fault accident. Shit like this just happens in wrestling. The hurricanrana isn’t an insane move, at least not any more than other standard wrestling moves, not even off the top rope. Making it look like it is, that’s the work.

You’ve got two guys: the guy who gives the hurricanrana and the guy who takes the hurricanrana. The taker does a lot of supporting work here. That’s pretty common in wrestling, unless the giver is unusually strong or acrobatic. The giver does a box jump and the taker gives them a boost to help get their thighs or knees around his head. The giver throws himself backward in a 180-degree flip, while the taker does a standing somersault above the giver as he falls. Adam and Carrion did this the right way.

"It wasn't like he took a crazy move or took a crazy bump," Meehan said. "It seemed like he kind of landed awkwardly and injured like a muscle or something, like he tore something. And it wasn't because Adam was unsafe, it wasn't because [Carrion] was unsafe. It was just one of those things. Some of the most extreme injuries that I've seen in professional wrestling don't involve anybody doing an extreme spot.”

“I have a stellar reputation when it comes to protecting people and protecting myself and you know, making sure precautions are taken and we're not doing unnecessary stuff,” said Adam. “But, it's heavy, man. It's heavy. I blamed myself a little bit, but rewatching the video, it’s just a freak accident. But it’s definitely something that I still beat myself up about. I just wish I could help.”

After the match, Adam and some other people took off Carrion’s boots and kickpads and elevated his feet. Carrion’s knees looked normal; maybe it was a calf thing. He stuck around for most of the rest of the show before someone took him to an urgent care clinic.

What’s it feel like backstage when you watch a guy get hurt? “You know that they're going through this range of emotions, where they're like, Oh, man, what, how bad is this? Am I going to be able to wrestle anymore?" said Luigi Primo, who was also working the show. "And you know from experience that that's just a heartwrenching, heartwrenching thing to feel. There's also this ‘there but for the grace of God go I’ moment where you know it could be you.”

After three rounds of X-rays and an MRI, a Dallas-area hospital told Carrion he needed a plate in his knee. A fan pitched in the down payment so Carrion, who was uninsured, could get in the door, but she couldn’t pay any more than that. He panicked. It would be July by the time he could walk normally and be able to work any kind of job—assuming he could pay for physical therapy.

“This has been a sudden shock to not only my body and mind but also to my economic situation,” wrote Carrion on the GoFundMe he started to cover his bills. “I’m now unable to work for a long period of time and covering my medical expenses as well as my living expenses has already been a challenge. My cell phone service has been cut off and my car has been repossessed among the problems I already face. I don’t ... have family to turn to under these circumstances. I understand that times are difficult for everybody but if anyone is able to donate whatever they can to help me get through this. Anyone who knows me personally understands how hard it is for me to ask for help but this situation has reached a critical point where pride must be set aside and reaching out for help is my only option.” His goal was $30,000. He raised $4,070.

In March, I found him on Twitter. “I’ve been suffering," he told me. "I’m trying to figure things out and I’ve been turned away by so many medical facilities because I can’t pay them up front. It has destroyed my life.”

In April, Carrion posted a photo of something poking out of his knee, under the skin. ”I have a screw sticking out the other side of my bone and it’s been hindering my progress and causing me pain,” he texted me from the hospital. “I’ve been medically neglected for weeks.” A few days later he deleted his Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. A week later my iMessages stopped going through.

I called around. Nobody knows where Jonathan Carrion is anymore.

How do you keep a wrestler from self-destruction?

An outsider looking at the condition of independent wrestlers might blame wrestling promoters. For the billion-dollar WWE and major upstart All Elite Wrestling, that criticism is warranted. After much bad press, the major promotions now cover injuries sustained on-screen, to an extent. But no promotion offers its wrestlers insurance. The majors use their monopoly on “earning a living wage” to lock most of their talent into exclusive contracts as independent contractors, dodging the requirement to provide them with healthcare benefits.

The notion of “independent contractors” in wrestling is, of course, bullshit. Workers who get a contract with WWE aren’t allowed to wrestle anywhere else. Their professional lives are owned exclusively by the company. But outside the billionaire promotions, there’s just no money in indie wrestling to pay for healthcare. The bigger indies are selling $25 tickets to a couple hundred people, tops, once or twice a month, and wrestlers work for (and thus can get injured on) dozens or hundreds of promotions in a year. Wrestling promoters are a lot of things, even assholes, but they’re not getting rich from the business.

What about a union? For decades, WWE head honcho and sex creep Vince McMahon—a fascinating, evil person and the most powerful man in wrestling history—has crushed all unionizing efforts. Jesse “The Body” Ventura, who had joined the Screen Actors Guild while working on Predator and saw what unionization could do for workers, tried to get one together in the ‘80s, but McMahon, tipped off by Hulk Hogan (who hasn’t found a billionaire he won’t cape for), killed it.

The size, disjointedness, and permeability of the indie wrestling scene make it challenging for a worker to demand more pay. And even if a bunch of them were to band together, it would be easy for promotions to pick up replacement-level scabs. “If I were to walk into a place and say, 'I won't leave my couch for anything less than 500 bucks,’ someone else will, in a heartbeat, try to do the same thing I'm doing for $20,” said CPA. “They won't do it as well as me, but they will try. And that's the problem with pro wrestling: There will always be someone who's gonna say, ‘Well, I don't need to get insurance. I'm just happy to be here. I'm just living out my dream.’”

Pro wrestling just doesn’t fit neatly into the traditional union structure. “It makes me think about the problem with musicians’ unions," said Kim Kelly, a labor writer who has covered labor issues in pro wrestling. "How they only really represent orchestra or Broadway musicians, and there are way more independent bands and artists out there with no representation. Independent contractors can’t unionize. That’s the real motherfuck of it all.”

That there is no stable, sustainable health finance mechanism within independent wrestling which will prevent financial disaster is less about the particular qualities of wrestling and more about the arrangement of American health finance. The 21st-century liberal vision of market-based healthcare is predicated on the assumption that everyone works a 40-hour-a-week job. Other countries—Canada, the U.K., Australia, Brazil, Taiwan, Cuba, Norway, many more—don’t have problems like this. A more just society might cover the medical costs for all its people instead of delegating this job to incredibly profitable private insurers and their fabulously wealthy executives. The medical industry isn’t off the hook here, either: America’s grossly inflated medical costs make hospital administrators incredibly rich as well, something the private market has shown itself unable to regulate.

“I'm for free healthcare for all,” said Cabana. “It gives me a lot of anxiety, our healthcare system. My savings is literally called my ‘cancer fund,’ just because I assume one day I'll get cancer and then I'll have to pay so much money that I need to save as much as possible. That's not a thing in any other country except the United States.”