There are a number of good reasons why most people do not pursue sprawling and ambitious high-stakes financial grift as a career. Just off the top of my head, and speaking only for myself, I've got "my personal values" and "don't like talking on the phone." But another reason that I think is at least as valid and compelling as "it is illegal" is that living under the pressure that sort of grift creates seems fucking exhausting. The basic pressures of a normal life are extractive enough; choosing to introduce to that already taxing mix the experience of being hounded by creditors and ripped-off business partners and various and variously unhappy state agencies is just not a decision that I would make. This is one reason why I did not pretend that I had enough money to buy the Washington Commanders in a straight-up cash-on-the-barrelhead $7 billion deal, and then sue Bank Of America for $500 billion in damages for actions that allegedly prevented that deal from going forward.

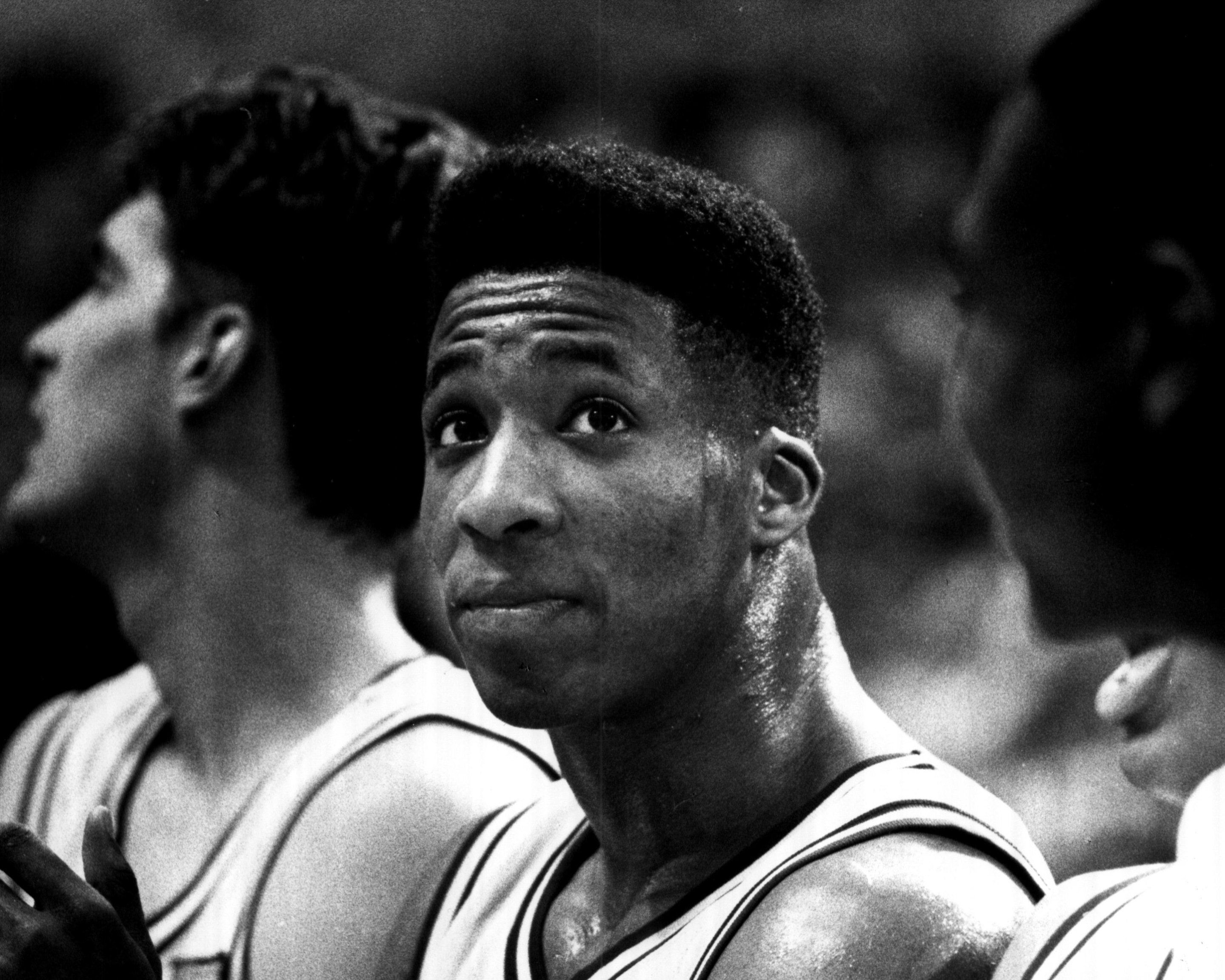

Brian Davis, during a long career of doing things more or less like that, has never let any of those considerations hold him back. Davis was a prominent supporting player on some great Duke basketball teams in the 1990s, then washed out of the NBA after one season spent as Christian Laettner's emotional support teammate in Minnesota, and has since made a name for himself as a real estate developer and entrepreneur, and more specifically made a name for himself as the type of real estate developer and entrepreneur who is constantly getting sued. It is the grimmest and most hopeful possible understatement to say that this is a familiar character type in American life, and Davis has mostly inhabited the role in a familiar way—taking out loans and soliciting investors for real estate developments that mostly didn't happen and then getting sued for not paying those loans back, and then starting new holding companies and trying it all again. Davis, in partnership with Laettner and on his own, had done this for (notional) real estate developments in New Jersey and Maryland and North Carolina and Pennsylvania and Washington D.C.; he has been sued by Shawne Merriman (in 2009) and Scottie Pippen (in 2010) and Johnny Dawkins (in 2012) for not repaying debts. By the time those suits were filed, Davis had begun aiming very high indeed.

In 2006, Davis and Laettner solicited investors for a bid to buy the Memphis Grizzlies that never came to fruition; Pippen was one of the investors in that gambit that didn't get his money back from the duo. "I’m going to be patient," Grizzlies owner Michael Heisley said in December of 2006, months after he'd last spoken to Davis and weeks before the deal was set to close. "I’m not going to get into speculation on whether he can or can’t do it. ...The man is spending and has spent a significant amount on this project. For people to dismiss it as a fraud is inexcusable. Why can’t people wait to see if he delivers?"

Davis did not deliver, and while he and Laettner successfully brought together a group of investors to buy the MLS side D.C. United in 2007, the two sold their minority stake in the club in 2009 for what Pro Football Network estimated was "a payout of under $1 million for the two of them combined." None of this, and nothing that Davis has done in the years since, indicated that he was someone who would be able to deliver $1 billion in cash within 24 hours of finalizing a purchase of the Commanders. But the public announcement that he might, along with a willingness to fully indemnify former team owner Daniel Snyder, cover Bank of America's nine-figure closing fees, and pay $1.5 billion more than any other bid, was enough to get Davis ... well, a bunch of well-researched blog posts detailing the many times he'd previously been sued for breach of contract, mostly, but also some interviews on local D.C. television and sports radio last month.

Davis did not really light it up, there, although he was taken seriously enough to be permitted to go on big local shows and talk in rapid, confident circles. On D.C.'s WUSA TV, Davis claimed to be a "LEED certified developer," which is not a thing that exists; the U.S. Green Building Council, which awards LEED Certification to qualified buildings and not individual human people, showed no record of ever having certified any of Davis's developments. "Our development,[scandal-plagued but extant Durham, N.C. residential development] West Village, was the first LEED certified and green development in the country and that’s a fact," Davis told a D.C. radio station, although this was not in fact a fact. "As I said, I am not Nikola Tesla but I am the person who has been doing the same thing for 25 years."

It went on like this for a little while, less because Davis actually had a shot at buying the team—the sprawling consortium headed up by Josh Harris always seemed to be the favorite, if only because they undeniably had the money—and more because Davis didn't want to stop talking. "It was impossible for the hosts to get clarity from Davis on the basic question of whether he personally has the requisite $2.1 billion in his own money to support a $7 billion bid," Pro Football Talk noted of Davis's 30-minute interview with D.C.'s Sports Junkies radio show. Instead, Davis underlined that he'd made his $50 billion personal fortune through the sale of intellectual property relating to a solar-powered smart-city concept. That concept is strikingly vague, and has no online footprint to speak of. "I’m married for 23 years and have three sons, two at Duke right now," Davis told the Junkies:

"And I learned from my past. I created special purchase vehicles for each deal and made them new companies. For this cash advancement, I created Urban Echo Energy so it wouldn’t have a history. I didn’t want my investors exposed to anything that happened years ago. So, I’ve created about nine different LLCs where I have 100 percent controlling interest so I can keep it simple, and I don’t have a website or market because I’ve been focused on getting the capital in—and this is where I talked about the intellectual property. That’s my capacity to build a business model where investors can legitimately see how they get return on their investment over the years. It hasn’t happened yet because I’ve been trying to develop something that has transformative impact.”

In response to reports that some portion of his sudden wealth came from Saudi Arabia, Davis asserted that his bid's funding "comes from white people ... who are Jewish, Italian, and Sicilian." The $2.1 billion that he, personally, would need to have to qualify as the lead owner on that bid was, Davis said, his and his alone. "This is my Redemption Song," he said. "I’m hoops Bob Marley!" Six days after submitting his bid, Davis was sued by a Northeast D.C. man for failing to repay a $322,000 loan.

When the Harris deal closed, I made my peace with the fact that this story, which was one of my favorites of the year, had at last come to an end. This was, again, a case of me—an intermittently normal person who inhabits a world in which things actually ever end—underestimating the size, breed, and hunger of the dog within Brian Davis. The Friday before last, Davis sued Bank of America for $500 billion in damages and sought an injunction returning the $5.1 billion that Davis claimed to have transferred to the bank. "The lawsuit alleged that $5.1 billion was sent by Urban Echo and transferred to Bank of America in two different transfers." Front Office Sports reported. "Included in the court filings were images of two alleged copies of the bank drafts dated March 8." Davis's suit alleged that BoA failed to deposit those funds. "As a result of BOA’s wrongful detention of Urban Echo’s property," the suit alleged, "Urban Echo has suffered damages, consisting of the return of Plaintiff’s $5,100,000,000.00 and additional damages in an amount to be proven at trial."

Last Friday, as part of that legal proceeding, Bank of America attorneys said that "the documents we have in our possession raise considerable concerns about their genuineness." If those documents, which include an image of a check made out for "Five Billion And No100ths" dollars, are indeed fake, Davis could "face some legal risk," according Front Office Sports.

Davis is not the first person to try to buy a professional sports team with money he didn't have. John Spano tried to do it with the Dallas Stars in 1995 (former Stars president Jim Lites told Sports Illustrated that Spano was "the only prospective sports owner I ever saw who wanted you to pick up the check") and then somehow successfully did it with the Islanders in 1996; he wound up spending 71 months in prison. ESPN made a 30 For 30 about it. "Spano admitted his crimes," Richard Sandomir wrote in The New York Times in 2013, "but claimed that it was easier, through fraud, to get an $80 million loan to finance his purchase of the Islanders than it had been to get his first car loan of $12,000." In Spano's case, as in Davis's, it's hard to tell what exactly the plan was for seeing it all through; in terms of the basic impracticality of it all, it's not so much a case of the dog catching the car as it is that dog subsequently assuming the car payments and insurance. The prices only ever go up, but a salesman is got to dream.