On Sept. 19, 1994, a week before Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell declared that there was no legislative path forward in the current Congress for the Clinton administration's healthcare reform agenda, NBC aired "24 Hours," the pilot episode of ER. Set across a single day in an urban emergency room, the episode introduced a cast of medical professionals including John Carter, a medical student on his first day at Cook County General, played by a fresh-faced Noah Wyle. Wyle would be the last original cast member to leave the show, at the end of Season 11 in 2005, by which point ER's status as the anchor of "Must-See TV," the most watched night on television's most watched network, meant less than it used to.

The Pitt, which premiered in January and has its Season 1 finale coming up in a couple of weeks, also begins as a new rotation of med students arrive at an urban hospital's emergency room, and are shown around the ER by Wyle, now playing the senior attending physician, Dr. Robinovitch—"Dr. Robby" to his colleagues, and to us, a great TV name, the soothing childlike nickname of a competent, twinkly doctor crouching down to eye level to build rapport with a nervous young patient. Created by ER vet R. Scott Gemmill, the show also unfolds across a single day—an hour per episode, in subtly compressed real time—with numerous callbacks to the NBC drama, including a much-teased fakeout on the hospital's helipad, and an emergency-room childbirth with complications which Dr. Robby is able to navigate more deftly than Carter's old ER mentor did in that show's most acclaimed episode. But The Pitt, unlike ER, is a streaming-only show, developed for Max, the Warner Bros. Discovery platform that evolved out of HBO's on-demand service.

Word of mouth seemed to hit critical mass after episode 12, at the end of March, as the casualties from a mass shooting at Pittfest, a fictitious music festival with an apparently very diverse lineup, started pouring into the ER, and the cast, supposedly at the end of their shift, stayed on for overtime and a few more episodes. A new friend descends into The Pitt every week, and within hours becomes so pitted. "We used to make things in this country (well crafted workplace procedurals)," to quote one member of Pitt Nation, is the common sentiment, along with nonstop memes of Mel (autistic queen, protect at all costs), Dana (hottest woman on the planet, need her so bad), and Dr. Robby, who was just named Time's Person of the Year for 2025, the first time the magazine has ever announced the designation in April.

How did we get so deep in The Pitt, so fast? Around the time tragedy struck at Pittfest, Vulture checked in with HBO executives on the secret of the show's success. "Our intention is to do a high-quality show that years ago would've been done on one of the major networks, but to do it for streaming," longtime ER showrunner and Pitt executive producer John Wells told the publication. HBO CEO Casey Bloys filled in the details: a longer season; weekly episodes instead of a single bingeable drop; a quick turnaround before a second season; and a replicable procedural format like the many syndicated titles that fill in streaming platforms' content libraries, the kind of good-enough shows that drive retention. (Alongside recent heavy investments in live sports, the revelation that television viewers like formulaic reruns suggests that the streaming industry is moving into its "reinventing the bus" phase.)

Statements like these, from the executives responsible for developing and commissioning the show, make the subtext text: The Pitt is a reverse-engineered throwback; it feels new because it feels old. Though it features many of the characteristics of post-peak television—the episodes can't be watched out of order, and the characters are all sad because of things that happened in their pasts—it's also profoundly, gratifyingly normal. It knows what it's doing.

The filmmakers built 360-degree sets on a Warner Bros. soundstage, so the camera and characters could move from room to room; the walls stay where the walls are, and can't slide away for any elaborate dolly tracks or pull backs to a long shot, and the fluorescent tubes on the emergency room's ceiling are really LEDs, for greater control without setting up additional lighting just out of frame. In contrast to the elaborate single takes currently in vogue on quality TV, The Pitt is not ostentatiously directed; it favors an unobtrusive naturalism evoking classic direct-cinema documentaries like Frederick Wiseman's Hospital, with a handheld camera that's just shaky enough, as if you're squeezing in alongside the characters, that the very conventional coverage doesn't read as storyboarded. The cinematography feels realistic even though the editing is rapid and expository—here's a close-up of the doctor requesting a tracheal catheter for an intubation, here's a close-up of the tube going in—and this is a kind of immersion as well, relentlessly in service to the story.

The show's prosthetics, made by the special effects company Autonomous FX (they did Sydney Sweeney's pregnancy pouch on Season 2 of Euphoria), are lovingly handmade, medically accurate, and jump-out-of-your-seat grody. They teeter, like so much of the show, between the serious and the shameless. (Wyle explained, enthusiastically, of the rig customized to provide a full-frontal view of the birthing scene: "My hands were inside. The baby was in there. The baby's shoulder is caught on a pubic bone.")

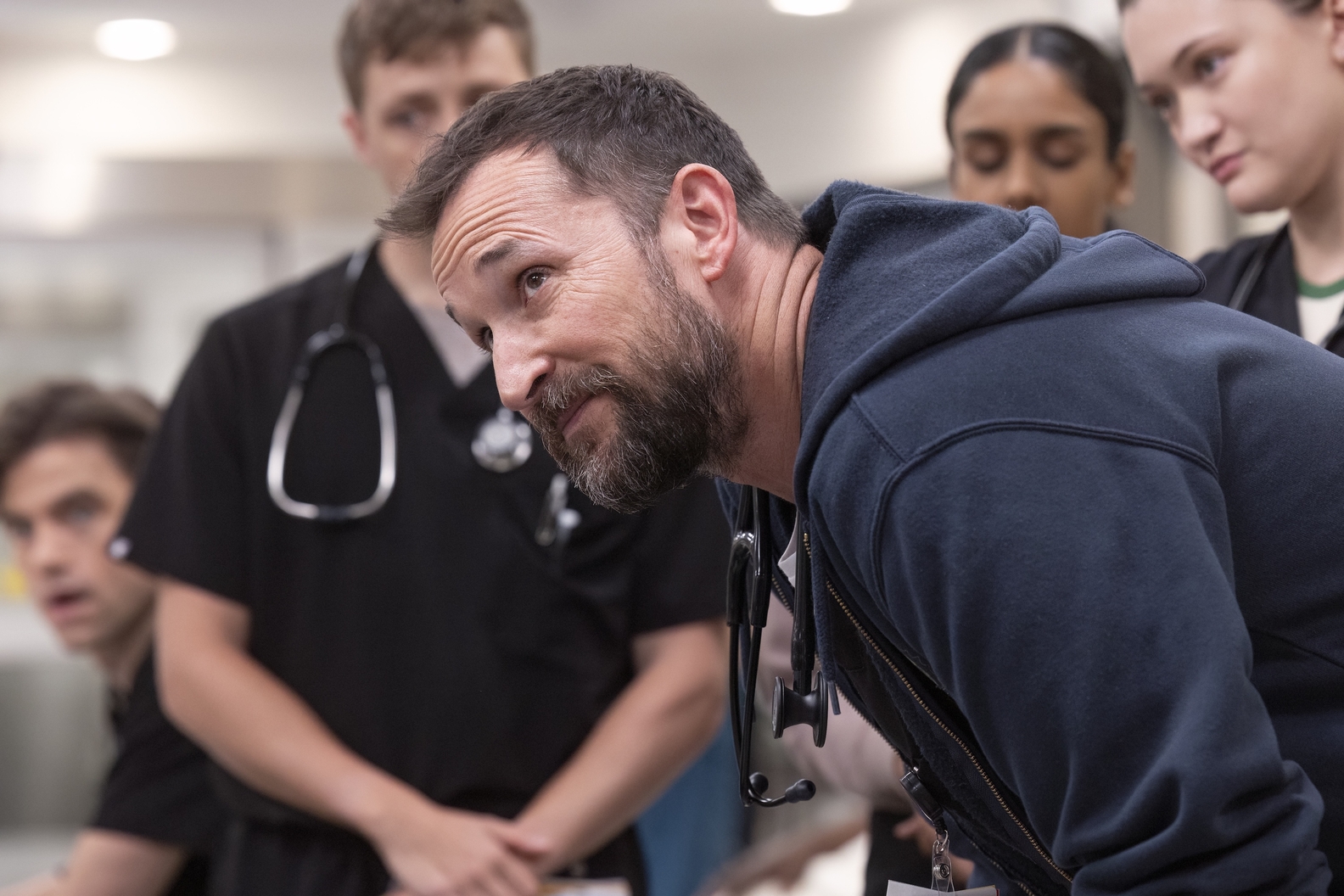

Aside from Wyle, the ensemble is relatively unknown—as of this writing, three of the 10 members of the main cast don't have Wikipedia pages—and they have bad, flat hair (except for Langdon) combed or cropped or pulled back from interesting faces. There are minimal personalizing touches over the uniforms of scrubs—a hoodie, a headscarf—and we don't know much about who they are outside of work, but we know enough, because of the personality that the actors let flicker through in the arrogant or anxious way they request a few CCs of ketamine for a patient.

None of this is new in workplace procedurals, where the specificity of jargon-laden dialogue takes on the familiar, comfortable cadence of office banter. As they know each other, we know them, and the cast becomes more appealing the longer they stay with us in our living rooms. TV shows, set around recurrent locations right out of life like a hospital or TV studio or bar or family home, grow on you over the years and over time, as you and the characters age together, and though The Pitt is in its first season, it can lean on a tradition. Wyle is not a doctor, but he plays one on TV with sufficient grace and gravitas that I would consent to him performing surgery on a loved one without a moment's hesitation.

High-pressure dramatic situations form deep emotional bonds between you and the characters you root for, and The Pitt nurtures this relationship by portraying its healthcare workers as, frankly, unrealistically compassionate. Mohan is probably the wokest doctor in the Pitt, given her experience studying racial disparities in medical treatment and concomitant crusade on behalf of a misunderstood sickle-cell patient, but it's a close-run thing what with Mel's delicate handling of the neurodivergent table-tennis star and McKay's concerns over incel culture. This is a gentler standard of care than you are likely to receive in an understaffed public hospital, but it's the show's way of doing something network television has always done, which is to enlist sympathetic characters to learn about or lecture on ripped-from-the-headlines subplots in square, cringingly sincere dialogue. After cycles of Difficult Male Protagonists (The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, Mad Men) and Eat the Rich zeitgeist grabs (White Lotus, Succession, Industry), this return to the medical procedural is middlebrow liberal comfort viewing, as much for the competence of its characters as the competence of its storytelling.

The emergency room is a place where something is always happening, where topical or colorful guest stars come in all the time; as writers and producers have always known, this is great for the Sisphyean demands of the network schedule, when there's always another hour of screen time to fill. Ailments can vary widely: the body horror of the prosthetic degloved foot in the show's first hour; the scatology of the sprays of blood and urine repeatedly ruining Whitaker's scrubs; the straightforward earnest tragedy of adult children saying goodbye to their dying father. The tonal whiplash and compressed environment makes things tense, breathless; you're at the mercy of the show in the same way a patient is at the mercy of a doctor cutting their windpipe open to insert a breathing tube.

The quick-hit pathos and more or less constant life-or-death stakes mean that the kind of viewing The Pitt inspires is reactive, not proactive as in the subtext truffle-hunt of a White Lotus or the withholding puzzle box of Severance. As a viewer, you're as passive as a patient, and discourse around the show is largely disbelief, excitement, fandom. "I'm so proud of Mel for stepping up like that" is a thing I said to my girlfriend after Hour 12, when Mel gave blood during the mass casualty incident.

Online fan activity, like recaps and discussion boards, helped lay the groundwork for TV's acknowledged Golden Age (years before Emily Nussbaum won a Pulitzer, she was a regular in the Buffy forums on Television Without Pity). Much of HBO's Sunday night lineup is designed to inspire Monday-morning thinkpieces—after Game of Thrones or Succession you can game out the realpolitik, speculate on psychology, analyze themes. The Pitt is for Thursday nights, like ER: a reward for getting through most of the week, neither condescending nor pretentious. It doesn't insult my intelligence, nor does it flatter it unduly. It's glancingly relevant—the show explicitly discusses the effects of private equity, post-COVID burnout, the nursing shortage, and a general breakdown in social trust on an already teetering healthcare industry—and conspicuously well-made, with character arcs like McKay and her ankle monitor, or Javadi and her mom, that are all the more satisfying for building to obvious payoffs. But it's also a crucible of comically deep human suffering in which Dr. Robby is tortured like a lab monkey at the hands of a God even more capricious than Job's, and where the most empathetic doctor in all of Pennsylvania is there to help if you have a mental breakdown brought on by the high mercury content in your imported skincare products.

Fifteen episodes, closer to a network order, with more filler and more tonal variance, is a step backward in television's artistic evolution. TV became respectable when it became an author's medium, a unified novelistic whole with all loose plot threads tied up neatly by a single governing sensibility, usually a man named David; next to the work of Chase and Simon and Milch, ER, with its large writers' room filling up 20-odd hours of television per season, began to seem stodgy and sensational. But the first-thought-best-thought expediencies of television writing also make The Pitt feel messy and heterogenous, like life is. Something was lost when the creative energy in television evolved past the big-tent populism of the network drama, past the tasteful soapiness and cautious didacticism.

Because the thing is, despite the title of this blog, The Pitt, being a Max Original, is not actually on television, and the performative enthusiasm surrounding it is also tinged with sadness that a show this normal—this solidly made, reliably entertaining, and broadly appealing—is not the steady foundation of a shared culture. (As Bloys said to Vulture: "Just think about NBC Thursday nights." Believe me, everybody is.) Across the second half of the 20th century, medical dramas delivered an idealized portrait of a universal public institution; maybe that's an obsolete model at a time when TV is hardly the only institution dealing with the breakdown of the old consensus. Word is that measles and maybe even polio are poised for a big year.

Among my friends, "We used to make things in this country" is a phrase that pours out of us reflexively, like a gesundheit, whenever someone mentions watching, like, a perfectly fine John Grisham adaptation with a dumbed-down political hook and superlative check-cashing supporting performance from Gene Hackman. With the benefit of hindsight, we now categorize these as the "mid-budget movie for adults" that has vanished from our multiplexes for macroeconomic reasons that have been good for the sovereign wealth funds betting big on streaming but disastrous for the babysitting industry. When we say that we used to make things in this country, we're parodying, a little, our crankiness at the state of art and the world, but the nostalgia—for a baseline of craftsmanship supported by a healthy domestic culture industry, maybe by a healthy culture in general—is real.

I do not wish to overly romanticize our past, cultural or otherwise. The network procedural gave us '90s ER; it also gave us ER's spottier later seasons, and could never have given us a Sopranos. I can recognize where The Pitt is corny, and on-the-nose, and straining. I could question whether it downplays the well-documented problems of arrogance and bias in medical professionals, or sidesteps larger systemic issues in the broken American healthcare system by personalizing the drama. But the truth is, I'm too worried for Dr. Robby, who, again, is a real doctor who could heal me (even if he can't heal himself). He's trying his best; so is The Pitt. It's nice to be in good hands.