As the weather cools and the kids return to school, my social media feeds have been inundated with fall trend forecasting: "What cool girls will be wearing this fall" and "The Row Margaux dupe you NEED."

Nearly as prevalent in my feeds are the de-influencing videos. While influencers work to persuade their audience to buy products they may or may not need in the hopes of getting a few cents of commission, de-influencers remind people why they don’t need to spend their money. De-influencing material ranges from explaining why individual viral products aren't worth buying to entire accounts built to remind audiences that hauls aren't normal and call out undisclosed ads or partnerships with brands. De-influencing is part of a larger populist turn I've noticed in response to the omnipresent commercialization of the social internet, but it also exemplifies one of the internet's signal conundrums: Is it possible to create anticapitalist work on social media?

De-influencers have been around for a minute. NPR wrote about them in March, calling the phenomenon "a backlash to advertising" that could "have a surprising and real-world impact on the environment." The concept has existed long enough for people to have built solid, consistent brands on it.

Paige Pritchard is one of the first de-influencers who came across my feed with her real-talk videos reminding her followers that buying things won’t actually fill the voids in their hearts. Her Instagram and TikTok accounts have more than a million followers combined, and in addition to her social media content, she publishes a podcast and offers a coaching program to help people stop impulse shopping. According to her website, she has a life coaching certification from The Life Coach School, but no other clear qualifications for giving financial advice, besides having gotten out of debt herself. Because she uses the same social media tools as influencers to get her message out, her accounts start to look an awful lot like the influencers she critiques, except she’s selling her own digital products, not Stanley Cups.

Pritchard isn't the only one. Chelsea Langenstam is a Canadian creator who posts about budgeting and personal finance—and yes, de-influencing—and also sells digital budgeting templates and offers one-on-one calls to advise on budgeting, but also on content creation.

Then there are creators who don't necessarily identify as de-influencers, but who make de-influencing content while also linking to their Amazon storefronts to promote products they'll make commission from. Even full-on influencers will post de-influencing content; while I was scrolling through the top de-influencing search results, I found this video from fitness and lifestyle influencer Sydney Adams King with the text "let me de-influence you." Last week, she posted a Lululemon haul ad.

Not every de-influencer has pivoted to entrepreneurship. Diana Wiebe, who posts de-influencing content for 200,000 followers on TikTok under the handle DepressionDotGov (hell yeah), said in a video that Shein and Temu had reached out to partner with her. That obviously would've been a horrible fit for content she makes, which primarily calls out the "garbage" people buy in Target hauls, but I do wonder what brands, if any, would meet the bar for partnerships.

While I question the ethics of offering financial advice without formal accreditation, I don’t necessarily think Pritchard or Langenstam are hypocrites with nefarious goals. In the most basic sense, they are reacting to, and hoping to disrupt, what social media has become for most users: a place to numb out and be sold to.

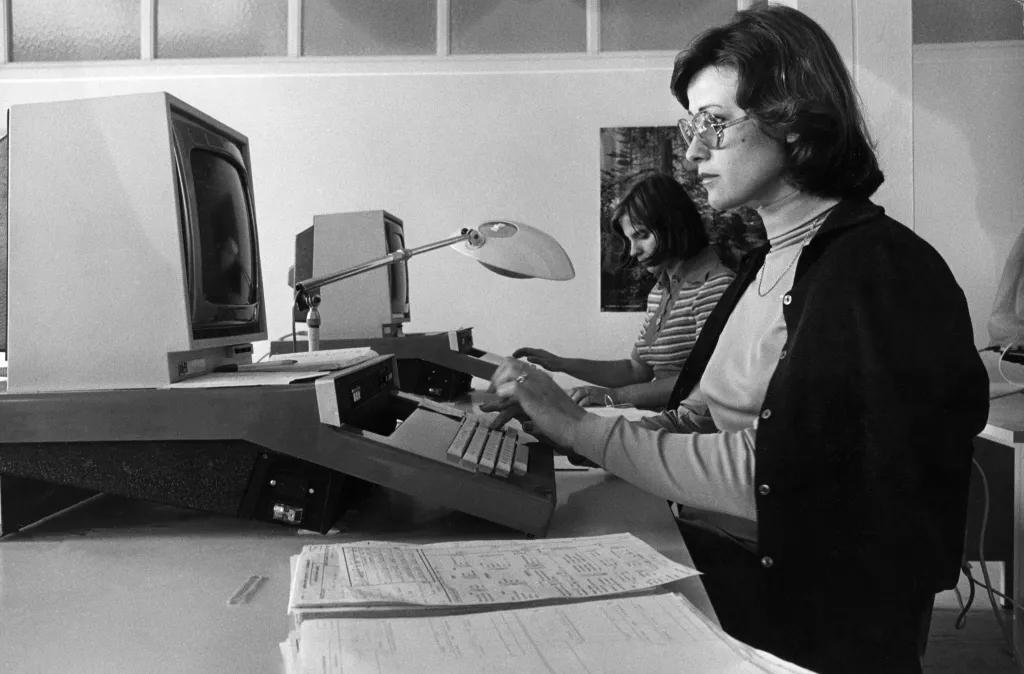

When social media started, these sites were places to hang out. Your accounts were avatars that represented you to the people in your world. Your friends were your friends, not followers. Brands barely existed online, and there was no such thing as a sponsored post. But as social media has evolved, the experience has become almost inextricably tied to commerce.

Attention on the internet—in the form of its metrics, followers, engagement, and reach—is nearly perfectly analogous to power and money. Even de-influencers, who are primarily interested in disrupting capitalist patterns on these platforms, must meet the algorithm on its terms. Once you have a million followers, would you be an idiot to not try to monetize that in some way?

Other recent mini-movements have seemed to share de-influencing's populist sensibility. In August it was "underconsumption core," a trend in which TikTok users showed off their frugality, usually soundtracked to "Don't Know Why" by Norah Jones. In May, after the Met Gala, users collaborated on celebrity "block lists," mass-blocking celebrities and influencers who hadn't called for a ceasefire in Gaza, under the idea that public figures not using their platforms to advocate for change should lose them. Also in May, users tried to game TikTok's monetization levers with the "pay off my debt" trend: extremely straightforward videos asking anyone who viewed them to simply let them play long enough for their creators to get paid.

The common theme is apparent. More ordinary people—that is, people without follower counts in the multi-thousands or formal management or relationships with brand PR teams—are feeling frustrated with the addictive, brain-ruining nature of these platforms and their relentless inducement to make strangers rich by spending money on things you neither need nor even particularly want. In one sense, de-influencers are an expression of this frustration. But also, in many specific cases, they are a monetization of it—and in that respect can come to be no different from influencers themselves.

In her essay "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House," Audre Lorde argues that liberation cannot be achieved by the tools of oppression: The master's tools "may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change." For the de-influencers using social media platforms to sell life-coaching and personal finance guidance as a sort of anti-capitalism juice cleanse, a fair question to ask is whether genuine change truly is one of their goals, and what they'd lose if it ever actually came about.