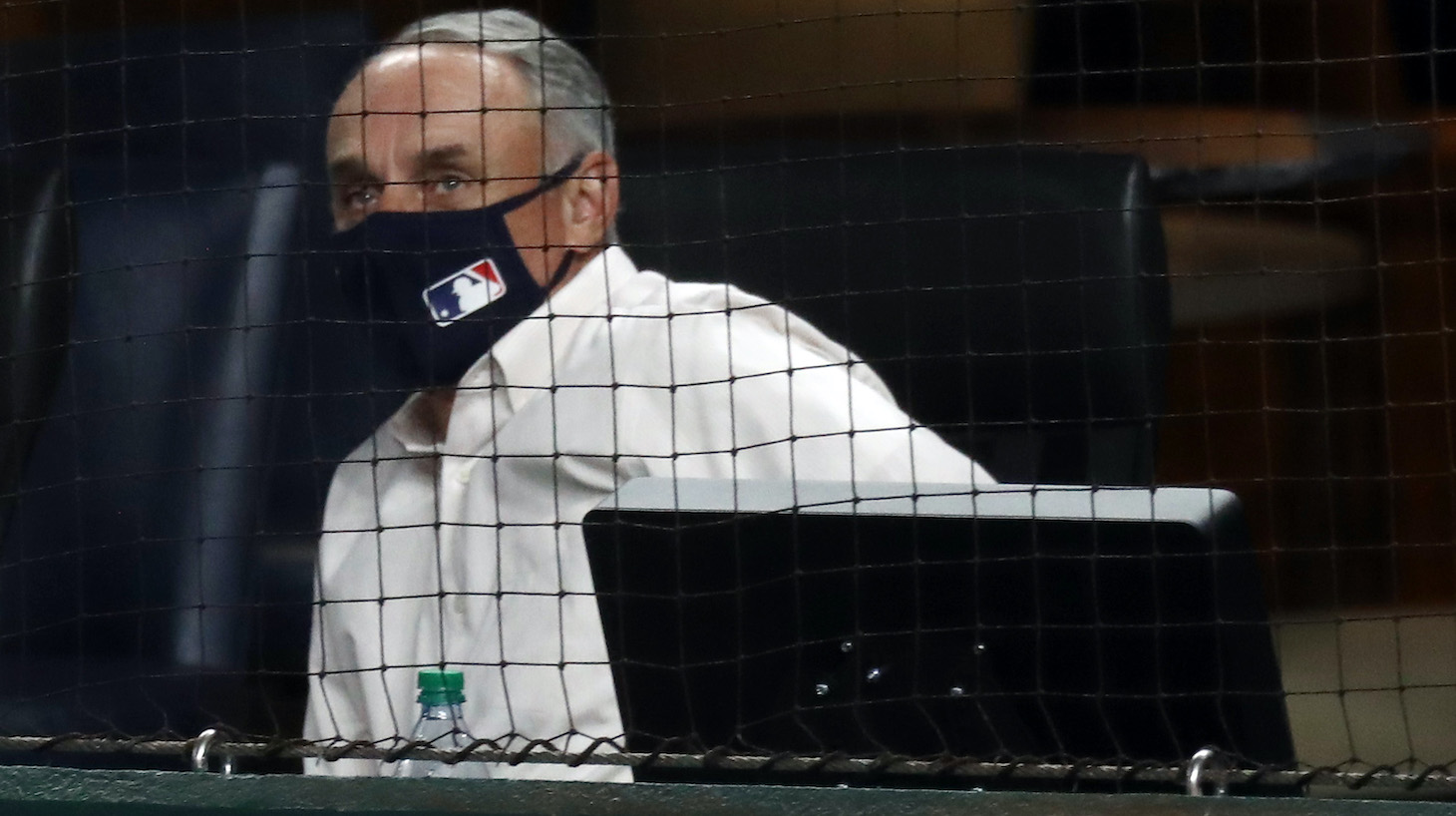

It seems Rob Manfred bristles a bit when his job description is explained to him by 11,000 people. He was vigorously booed when he presented the World Series trophy (and not credited when he didn't accidentally impale anyone with it), and he clearly did not enjoy the sensation. Unlike Gary Bettman and Roger Goodell, who in different ways have understood that their gig is actually to take money from owners while absorbing abuse that would rightfully be directed their way, Manfred handled his latest exposure to the hoi polloi as though he actually thought he was providing a service to a venomously ungrateful nation.

But Manfred is largely a cartoon villain anyway, a face for the 30 franchise owners who don't ever want to be accountable for the way they run their business—which, let's be honest, they think is a towering triumph since they are making more money than they used to by concentrating on how they distribute the games rather than on the games themselves. This is not about the game, in other words. This isn't even about the people who play the game. This is about being able to command the uniformed pixels to move on customers’ screens at the right time of day for the proper level of compensation.

By any measure, the owners' 2020 compensation was grossly inadequate to their desires; Manfred claimed to Sportico that the 30 teams are carrying more than $8 billion in debt among them, while an anonymous MLB executive told The Athletic that the industry lost $3 billion in this shortened season alone. Of course, they offered that figure to explain why many teams have laid off wide swaths of employees. Their primary interest, then, is in figuring out how to get back what they believe to be their rightful money, and they have hired people they value far more than Manfred to do those calculations.

But Manfred's role is to sell what the owners are pitching, and at that he has had a largely disastrous 2020 to sell. The folks who bring you baseball (as opposed to Manfred, who actually doesn't) wanted three COVID bubbles and got none. They wanted crowds and got none, until, inexplicably, the NLCS. They wanted to put the Houston Astros' sign-stealing scandal behind them and failed. They offered protocols for teams to follow, which weren't, and didn't punish anyone when they were caught. They even ruined a compelling World Series by letting Justin Turner and the Los Angeles Dodgers define the season as just another way sports refused to responsibly acknowledge limitations. Oh, and the television ratings were the worst since Philo T. Farnsworth roamed the earth. In many ways, 2020 baseball was a horror show.

They got their 60 games in, except for the teams that didn't, and they got their extended playoffs, and depending on when Turner and the Dodgers knew he was virused, they even ignored the most basic health and safety rules to cram in the Series. In short, the Dodgers, with one of the best teams the sport has produced in decades, and with an eminently sellable star in Mookie Betts and the redemptive tale of Clayton Kershaw, joined the 2017 Astros and 2018 Red Sox as champions who don't really get to enjoy being champions because they can't wear their rings without people looking sideways at them. That's three of those in Manfred's six-year tenure. If he can't stick the landing on the sport's highest achievement, people are going to ask why he, or we, should bother any longer.

So how much of this is specifically Manfred's fault? That depends on how you define his job. Is he supposed to make you feel good about the sport? If so, he failed. Is he supposed to oversee the safe and rational production of games? Based on this season, he failed. Is he supposed to present a competent and engaged face for the company? If so, he did only slightly more for the sport than Arnold Rothstein. Did he give off an aura of authority and company-wide respect befitting what the office was designed to do when it was conceived 100 years ago? Justin Turner provides the answer to that one.

One of the things we learned about sports in 2020 was how the sausage is not only made and packaged but how it is envisioned by its providers. The answer to the original question "Who will make the decision to stop playing if there is a second outbreak of the virus?" is what we all suspected it was: nobody. Nobody was empowered to because nobody wanted to do so. That was purely an ownership call, and no mere commissioner worth his job-survival instincts would have lasted trying to provide any visible independent leadership.

In that way, Rob Manfred did his job. He may give off every instinct of not liking anything about the job but the paycheck, and that includes even the onerous task of watching the games. But his constituency is not you, and his job description is not what you think it is; he is there to get booed so the suits of Guggenheim Baseball Management don't. He is there to get the games off no matter what dangers incur, and we'll know more about that soon unless the Dodgers decide not to release their post-celebration COVID numbers. He is there to do the unpleasant task of appearing in public and pretending to care about the job when the only reason for anyone to want to be commissioner ought to be to serve as a growth agent for and a guide to the game.

That's not Rob Manfred. That was never going to be Rob Manfred. He is who he is, who he is paid to be and nothing more: a mirthless master of ceremonies and occasionally ruthless labor negotiator. At a time when the sport desperately needs wisdom, deftness, and the power to do more than collect money, he is simply a less enjoyable version of Simon Cowell, if that's your idea of a good time. And even Cowell figured out the cynical value of letting strangers call you names.