Generally, I don’t take YouTube seriously as a critical medium, but the number of people who do makes it a little hard to ignore. The paltry amount of money that used to go to cultural criticism in the written form has ballooned in the social media space, particularly for slickly produced videos made by guys with invisible ring lights and the kind of voices that wouldn’t be out of place in that meme of that dickhead with his arm around his disinterested girlfriend’s neck. One such, more intellectual, version of this guy is a British YouTuber named Harry Brewis, who recently caught the attention of people outside his regular niche for releasing an admittedly impressive four-hour video that dives into the plagiarism problem that plagues this particular corner of the internet.

“Plagiarism and You(Tube)” does what it says on the tin, but, like, really does it. Brewis uses those four hours to build a very strong case that essentially argues that YouTube incentivizes plagiarism, which he does by minutely dissecting the crimes of a handful of the site’s more prolific plagiarists. By the end of it all, you can’t not be convinced that YouTube is the perfect place for very famous content creators to make their names (and lots of money) stealing from much less famous, often marginalized, often underpaid (if paid at all) writers. As Brewis says, “If you’re not as important, your ideas are up for grabs.”

Brewis opens the video by talking about the last time a writer won a major plagiarism lawsuit, which was 1980 (it was Harlan Ellison and Ben Bova against Paramount). He explains that he actually wanted a more recent example but—*pause* (this is YouTuber cadence)—there weren’t any. Brewis made “Plagiarism and You(Tube)” as his version of the billboard Ellison and Bova reportedly erected after winning their case, which read, “Writers: Don’t let them steal from you! Keep their hands out of your pockets!” The video currently has 16 million views, which I suspect is a few more eyeballs than Ellison and Bova’s billboard got. “For the foreseeable future, if someone else on here steals your work for money,” Brewis says, “there’s not much you can do except talk about it.” But there’s talking about it and there’s talking about it when your videos frequently get millions of views. Brewis is being a good ally here, it’s a theme that runs through the video, and it’s notable for how rare it is.

The first case Brewis gets into is that of Filip Miucin, a YouTuber who basically did bog-standard newsy type videos about Nintendo and used free giveaways (rather than good content) to build his platform to such a degree that he landed a job at IGN, where he proceeded to steal a review from a much less popular video content creator (Boomstick Gaming) and was promptly fired. It turns out that Miucin also stole text from Nintendo Life, Nintendo Wire, Engadget, Polygon, Wikipedia, a forum called NeoGAF and, most notably, one of his own colleagues at IGN. Brewis shows how Miucin turned text-based reviews into nonsensical and even incorrect scripts in order to cover up what he was doing (like the guy who turned a Mental Floss article into that popular Man Cave Video).

Brewis also importantly analyzes Miucin’s “apology” videos, which share similar themes with so many “apology” videos by remorseless actors. Miucin uses passivity instead of taking responsibility (mistakes were made, etc.) and attacks the people holding him accountable. Then there’s the familiar appeal to sympathy by claiming insecurity, as though, as Brewis points out, every writer in the world hasn’t felt this way. Ultimately, Miucin is summed up as a guy with no ideas, who is bad at his job, and who purposefully copied better writers who were under the radar (and therefore, in his mind, beneath respect). As Brewis put it: “Plagiarists seem to have this belief they are better than their targets, more important, more deserving of credit, [have] better politics, [are] a better class of person.”

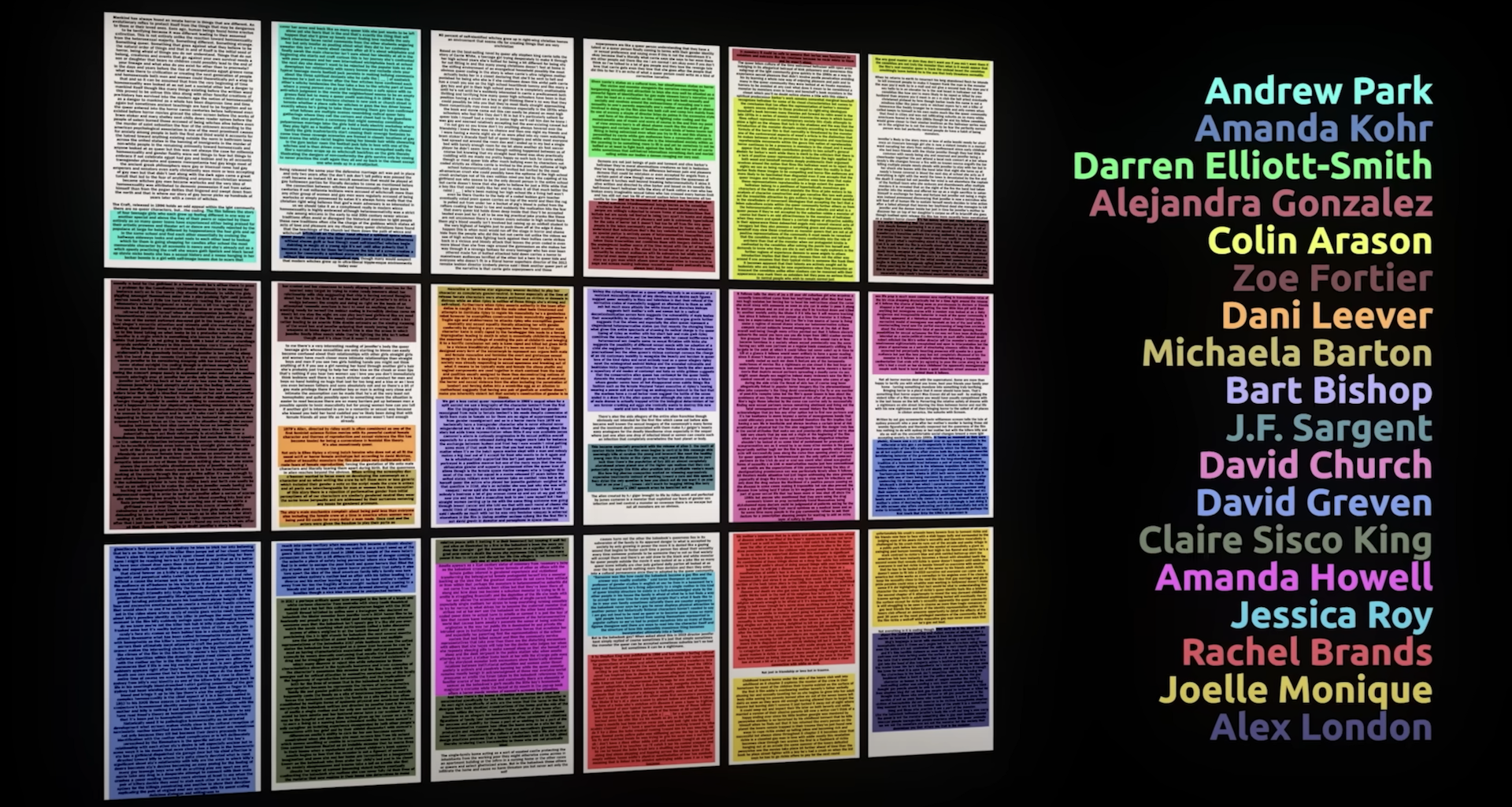

But the case that people talked about most, the case that really gets to Brewis, is James Somerton. This is a guy who positioned himself as THE queer cultural critic on YouTube, who advocated for representation by stealing work from the underrepresented. He made lengthy videos that were basically entirely lifted from Sean Griffin’s 2000 book, Tinker Belles and Evil Queens: The Walt Disney Company from the Inside Out, and Vito Russo’s 1981 book, The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies. Somerton was careful to appear authoritative with his very serious voice and very serious face, book by his side (not the one he had stolen from, of course), quoting esteemed critics like Susan Sontag, all while lifting swathes of text from lesser-known names like trans writer Jes Tom. There’s a great bit where Brewis illustrates the sheer volume of plagiarism in Somerton’s work by color-coding 10,000 words of text—it requires 18 colors. Like Miucin, Somerton is a guy with no real identity and nothing to say, so he has to rip better people off to make up for it.

Somerton’s case demonstrates just how far this con can take someone. He used his unearned YouTube popularity to finance a production company that simply took money and produced nothing, an old-school grift building off a new one based on intellectual deception. The content con artist is a particularly modern breed, stealing thoughts, ideas, and writing, which has been devalued online, only to make a fortune passing it off as their own in the very same place. They pull off this trick by diminishing the writer to nothing, while at the same time exposing the value of their writing by profiting off of it under their own name. It’s the perfect embodiment of the paradox of our time, in which writing is worth nothing while the content it creates is worth more than ever.

Content online is so often undergirded by the perspectives, talent, and charisma of marginalized writers. It is fueled by the rigor of the journalists who know how to find information and then weave fact into narrative. It is sharpened by the critics whose taste and breadth of knowledge, too, inform their analysis. And yet what allows this valuable writing to thrive—publications, newsrooms, publishing companies—is being actively dismantled. That leaves all those people who make all that valuable material resigned to other jobs and writing in invisible corners, their work even more vulnerable to those who are looking to cash in.

Of course not every influencer or YouTube critic is actively stealing from other people in pursuit of personal enrichment, but as Brewis points out, the system is designed to encourage this dynamic nonetheless, and they are helping to perpetuate it whether they want to or not. Platforms like YouTube favor packaging and presentation above all else. Where the ideas actually come from is beside the point.