Last Friday, Washington Post publisher and CEO Will Lewis announced in an editorial published on the paper's website that the Post's editorial board would not be endorsing a candidate in the 2024 presidential election, as it has traditionally done.

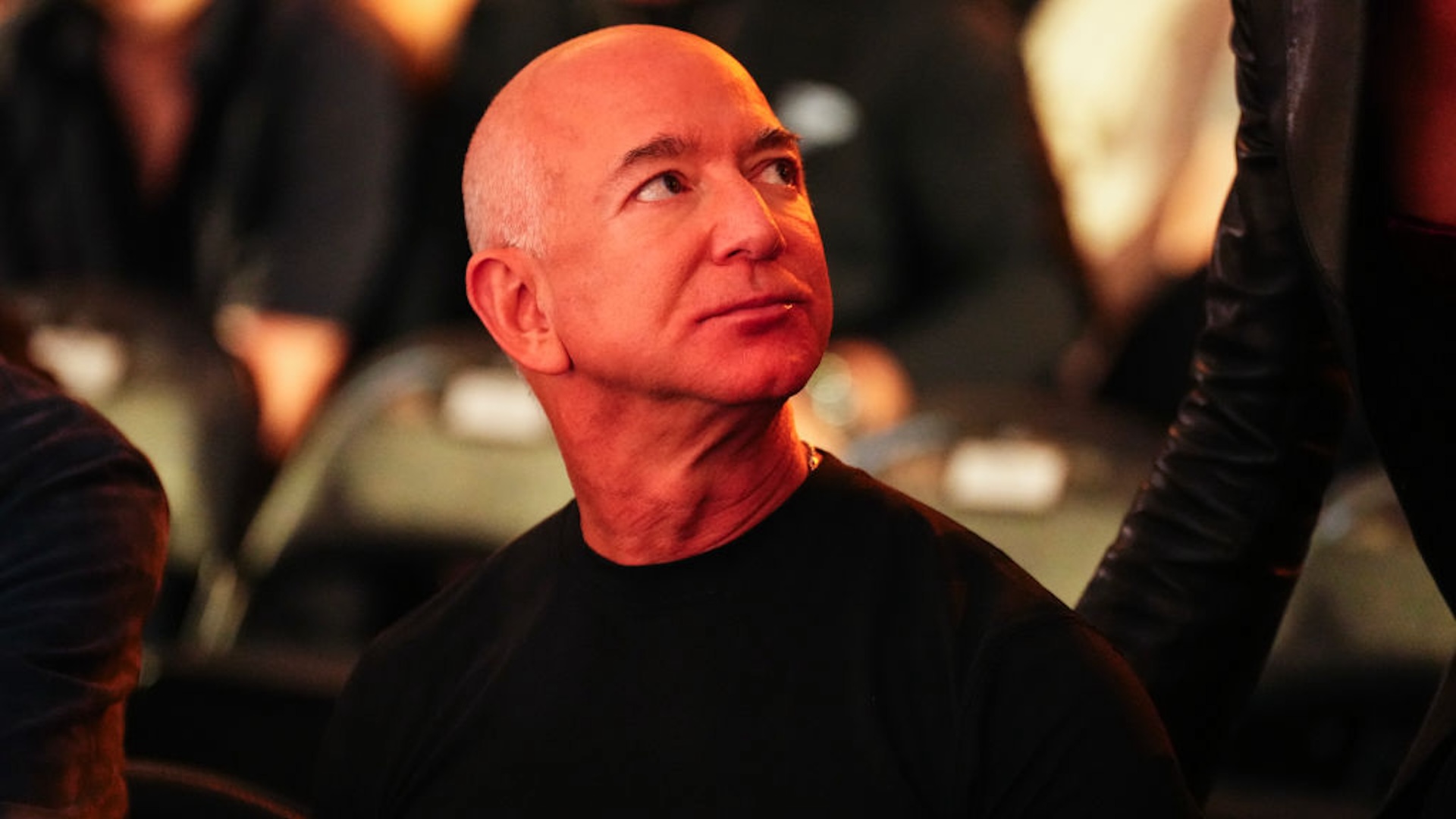

The backlash to this decision arrived swiftly and from all directions, thanks largely to reporting from NPR's David Folkenflik, who revealed that the editorial board had in fact drafted an endorsement of Democratic candidate Kamala Harris earlier this month. According to Folkenflik's reporting, the paper's billionaire owner, Jeff Bezos, reviewed a draft of the endorsement before Lewis announced that the Post would not be endorsing a candidate this year. Some Post staffers, faced with their publication's owner meddling in editorial decisions, revolted. A few published articles criticizing management's decision to nix the endorsement, while others submitted letters of resignation. A much bigger and more damaging reaction came from outside the paper: According to Folkenflik, at least 200,000 people have cancelled their digital subscriptions to the Post since the publication of Lewis's editorial, a number that represents roughly eight percent of the paper's paid circulation.

The writers and editors who resigned from the paper, and the readers who cancelled their subscriptions, all seem to have come to the same conclusion: Bezos, in an effort to make life easier for himself and his many business interests in the event that Donald Trump once again claims the presidency, had stained the Post's reputation by breaching the firewall between the paper's business and editorial departments. It's easy enough to understand how Bezos might have made such a decision. A national paper endorsing Harris for president does very little to move the needle, and it follows that Bezos would see a sound business decision in the speculative upside and apparently limited downside of ending such a rote and expected practice.

What Bezos failed to consider is that while an endorsement may not carry much weight among the Post's readership, its sudden and pointed absence very much does. A presidential endorsement may be among the least meaningful ways for a paper like the Post to broadcast its values and editorial vision, but it is one of the most immediately legible. Even if all an endorsement of Harris could accomplish is to reassure Post subscribers that they are paying for a broadly liberal publication, that knowledge is (now self-evidently) quite important to the 200,000 readers who cancelled their subscriptions over the last few days.

On Monday, Bezos attempted to stop the financial bleeding by explaining himself in an editorial, headlined "The hard truth: Americans don’t trust the news media." In his piece, Bezos tried to stop one conversation—about his craven meddling for the sake of currying favor with a fascist who might become president—by starting another one about the broader health of the media industry. After citing some poll numbers indicating that Americans do not trust the media, Bezos offered his explanation: He killed the Washington Post's tradition of endorsing a presidential candidate not to protect his own personal interests, but to help restore the nation's faith in journalism.

Presidential endorsements do nothing to tip the scales of an election. No undecided voters in Pennsylvania are going to say, "I'm going with Newspaper A’s endorsement." None. What presidential endorsements actually do is create a perception of bias. A perception of non-independence. Ending them is a principled decision, and it’s the right one. Eugene Meyer, publisher of The Washington Post from 1933 to 1946, thought the same, and he was right. By itself, declining to endorse presidential candidates is not enough to move us very far up the trust scale, but it's a meaningful step in the right direction. I wish we had made the change earlier than we did, in a moment further from the election and the emotions around it. That was inadequate planning, and not some intentional strategy.

Setting aside the idea that the universal trust of the public is something that a news organizations should be striving to attain (any newspaper worth a damn in 2024 is going to gain the trust of some readers while alienating others through its work), or that it is at all useful to gauge the public's trust levels in something as ill-defined as "the media" (if shops like Fox News and Newsmax are included in that tent, then why shouldn't trust levels be low?), Bezos seems to badly misunderstand his own premise. He admits in his own editorial that declining to endorse a candidate is not something that will, on its own, meaningfully increase anyone's faith in the Washington Post—but why wouldn't this choice damage that faith?

"Perception" is the key word in Bezos's apologia. An endorsement, made and explained by expert journalists who've spent years digging into politics and policy issues, is essentially a conclusion—no different than when a reporter assembles all the facts of a public health story, lays them out for readers alongside photographic evidence of sinister poison gurgling out of a drainpipe, and concludes that Multinational Company X is dumping carcinogenic waste into a river. This is pretty much the essential value proposition, to society, of having professional journalists: not that they can assemble featureless lists of disaggregated facts for layperson readers to grapple with, but that by digging relentlessly into a given subject and talking to experts, they can reach and explain authoritative conclusions. This company is ripping off its workforce. This rich shit-for-brains dilettante who looks like Irradiated Mr. Burns is destroying the newspaper he bought. This presidential candidate's policy ideas and general comportment align better with the normie politics and values anyone with a brain can identify as those broadly defining both our readership and our journalism.

There's no reason why that work, done responsibly and transparently by reporters, writers, and editors, ought to create any particular "perception of bias" among good-faith readers, who, even if disappointed by the paper's choice of candidate, could see for themselves the chain of reasoning that led it there. If anything, you could expect that it might somewhat increase their trust of the publication, for stating in print the location to which all its reporting and analysis has brought it.

Compare that with a recent decision that absolutely will, and already has, damaged the public's perception of the paper. That would be its billionaire owner descending from his dark tower to haphazardly snuff out a story as it was being prepared for publication—specifically for fear of revealing to readers a position the paper's editorial board holds and was ready to articulate in the open. This truth must be crushed and withheld by the paper's owner, you see, lest anyone perceive that the Post lacks independence. If he really wants to increase trust in his newspaper, he can start by staying out of his editors' email inboxes.

What's depressing about all of this is that Bezos and the people who have attempted to punish him by unsubscribing from the Post are suffering from versions of the same misunderstanding. A newspaper is not defined by its endorsements, nor the whims of its blinkered owner. It is defined by the journalists who dedicate their time to explaining the world to their readers. Those journalists can break stories and win awards and inform the public to the fullest of their abilities, but they will never escape the bind that capitalism puts all of us in, which is that consequences only ever flow in one direction.

One rich bozo can make a hasty, ill-informed decision that puts his newspaper's reputation through the shredder, and the only recourse available to an offended reader is a cancelled subscription. There is a righteous feeling to be found in doling out punishment by snapping your wallet shut—and in rushing to open it for someone else—but not everyone is exposed to the consequences of the market. Money is meaningless to Bezos, and so the only way for a story about his own buffoonery to end is with someone else paying for his sins. In this case, the Washington Post's rank-and-file journalists will have to deal with the consequences of 200,000 vaporized subscriptions. Whether budgets are tightened and jobs are lost will depend on Bezos's next whim. In the end, a billionaire can only ever own playthings.