On balance, you would rather have spent the six months of this baseball regular season as a fan of the Seattle Mariners than as a fan of the San Diego Padres. Both teams missed the playoffs, but the Mariners, who won 88 games to San Diego's 82, were in the thick of the playoff hunt right into the final weekend of the season. Seattle was atop its division as late as Sept. 4; the Padres were never atop the NL West after the second week of the season, and spent most of the back half of the season around 20 games out of the picture. San Diego's season was never anything but infuriating and demoralizing; Seattle's was often frustrating and ultimately disappointing, as has been the trend for them, but it was marked by real highs, as has also been their trend. The Mariners are reasonably good and reasonably cool.

But Seattle's 2023 season was a step backward. The Mariners won 90 games each of the past two seasons; last year they captured the American League's second wild card spot, eliminated the Toronto Blue Jays in two games, and played in a divisional series. This season the upstart Texas Rangers leapfrogged them in the division and the Astros remained something like the Astros. Mariners fans are frustrated. They are the only big league franchise never to make a World Series, it has been 22 years since they won a playoff series, the division is dominated by a juggernaut, and now the free-spending Rangers have successfully bought their way up in the line of succession. The Mariners, middling but tantalizingly close to contention, declined to upgrade their roster at the trade deadline, and instead dealt away their closer. Even their own players sense the time has come to get better players.

Catcher Cal Raleigh, stung by Seattle's elimination from the playoff race, questioned the organization's slow and steady refusal to take aggressive action. "We have to commit to winning," said Raleigh on Saturday, from the post-game locker room. "I think we've done a great job of growing some players here, within the farm system, but sometimes you have to go out and you have to buy, and that's just the name of the game. We'll see what happens this off-season, hopefully we can add some players and become a better team ... You look over in [the Rangers'] locker room right there and they've added more than anybody else, and you saw where it got them this year. So, there's more than one way to skin a cat, that's for sure, but going out and getting those big names—people who've done it, people who've been there, people who are leaders, people who have shown time and time again that they can be successful in this league—would help this clubhouse, would help this team."

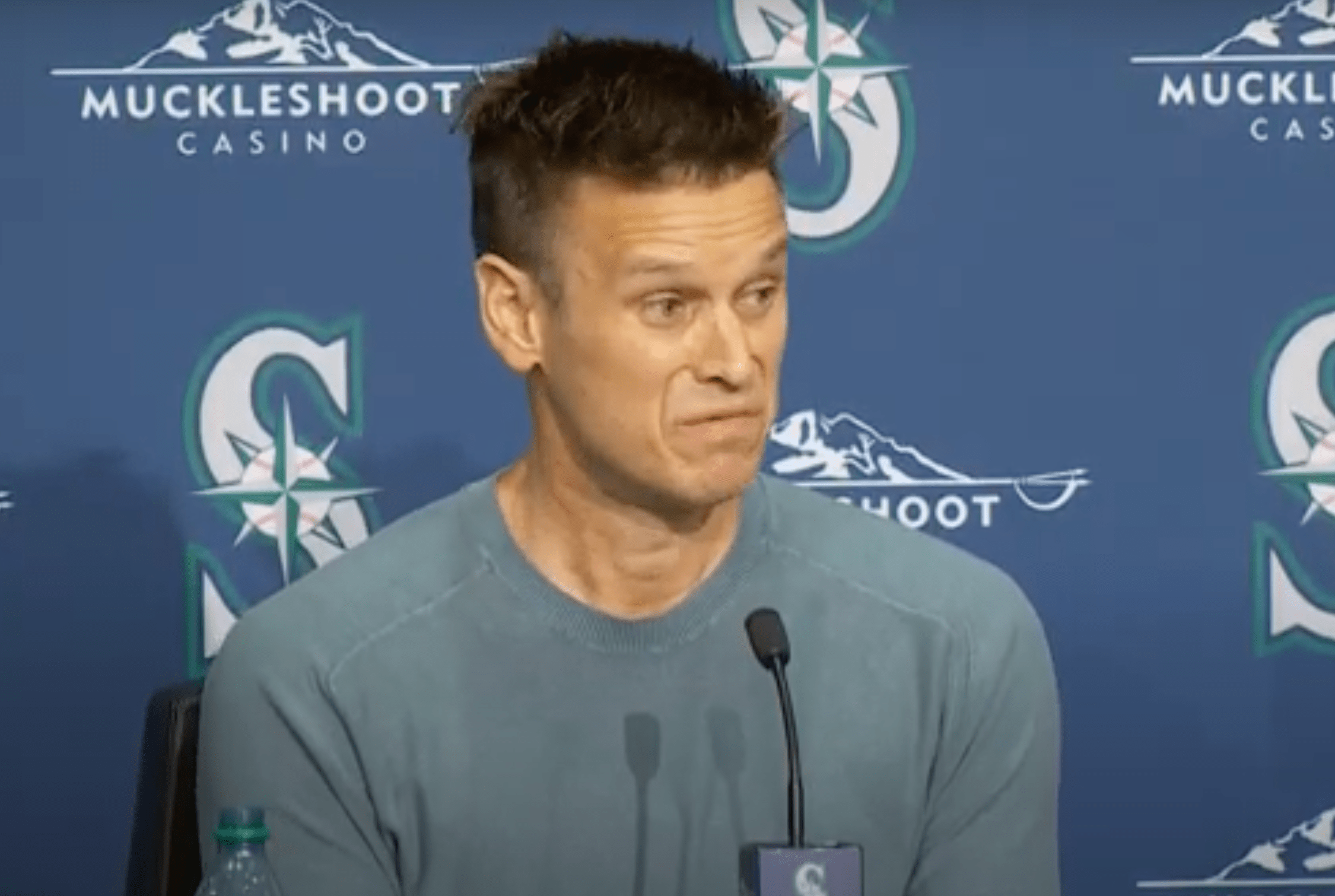

Tuesday it was general manager Jerry Dipoto's turn to address the state of the Mariners. Dipoto, who has been running the club since 2015, spoke directly about Raleigh's concerns. Certainly Dipoto has nothing against star-level baseball players. He thinks they are neat, in the way that you or I might think that for instance having a home movie theater would be neat. "Would I like to have big-name players?" asked Dipoto, rhetorically, in the manner of one who is about to tell their child that, no, we will not be buying a pony. "Sure, I think we all would." It's just that big-name players might not fit very well into Dipoto's extremely sophisticated plan for success. "I don't know that the solutions to our problems are big-name players. I'm not sure that we have big problems."

As Dipoto sees it, this season was "a step forward for us, organizationally." By winning 54 percent of their games and missing the playoffs, you see, the Mariners have positioned themselves more realistically for playoff success than a team that simply spends lots of money on big-name players. A team like, say, the Texas Rangers, who uhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh are currently in the playoffs.

“If we make winning the World Series our goal, we will do insane things that will cut the sustainability part of the project short. That’s not how we think. We think more broadly. We’re thinking over an extended period of time, and our goal would be that over that decade, you get to the postseason seven or eight times and are in a position to win it. In an ideal world you become one of the elite teams that go 10 in 10. The reality is, if what you’re doing is focusing year to year on what do we have to do to win the World Series this year, you might be one of the teams that’s laying in the mud and can’t get up for another decade."

Jerry Dipoto, via the Seattle Times

The binary that Dipoto is crafting here is, of course, baloney. Raleigh notably did not say that the Mariners should trade away everyone who is not named Cal Raleigh in exchange for the Wonderboy bat. The point he was making is that the Mariners continue under Dipoto to comport themselves as if they are organizationally distant from real-deal contention, and are waiting to see what is on the other side of the next wave of prospects, when in fact they could act decisively, loosen up the purse strings, supplement their roster with some big-time performers, and really try to distance themselves from the rest of their division. That doesn't always work, of course—the Padres, Mets, and Yankees are notable examples of big-spending projects that fell flat this season, something Dipoto alluded to in his Tuesday comments—but free agency and headliner trades are good, powerful, viable tools for building a contender, tools that other teams are using to accelerate their own contending timelines, or expand their windows of contention, or, yes, also to pay $245 million to Anthony Rendon. If a team isn't using every tool available, and this is crucially a thing that every big league team could do, are they really all that committed to winning?

Dipoto's own concept of sustainable winning is delightfully harebrained: "I can't tell you what year we're gonna win the World Series," says Dipoto. "I can tell you that if we win 54 percent of our games over the course of a decade, you're going to play in the World Series." Dipoto understands that this is not what Mariners fans will want to hear, that the team's GM is aiming for a 54-percent win percentage instead of, you know, rampaging to a World Series. "Nobody wants to hear the goal this year is, 'We're going to win 54 percent of the time.' Because sometimes 54 percent is—one year, you're going to win 60 percent, another year you're going to win 50 percent. It's whatever it is. But over time, that type of mindset gets you there."

This is a favorite trick of underperforming general managers across professional sports. I am building a consistent winner, here, and there are no shortcuts. And that means that sometimes my consistent winner will not actually do much winning. In fact, sometimes it might even do lots of losing. But lots of losing can in fact be an integral part of consistently winning.

Two years ago, when Dipoto undercut his spunky team at the deadline by trading their best reliever to their biggest rival, Mariners players kicked things and broke equipment and spoke of organizational betrayal. Dipoto hinted that only over a longer timeline—only with the benefit of a view that is evidently available only to Jerry Dipoto—would that move begin to make any sense. Two years later, these things start to click into place: It's not Dipoto's call whether the Mariners suddenly become one of MLB's big spenders—Seattle hasn't spent above league average in team payroll since 2018, per Spotrac—but what he wants, and what he is diverting resources toward, is the careful management of expectations. It's what was referred to in The Wire as rainmaking: When the process fails to produce rain, it's because the process hasn't fully run its course. When suddenly it rains, the rainmaker is poised to take all the credit.

In the meantime, no one is allowed to be mad at Jerry Dipoto. Mariners fans want to win a damn playoff series, for the first time in decades. They would like to see their team participate in a World Series, which again is something that it has never done before. Mariners players want not to be sandbagged by management. Jerry Dipoto would just like a little gratitude for protecting everyone from the pain of lofty expectations.

"We’re actually doing the fan base a favor," says Dipoto, giggling nervously but not joking, "in asking for their patience to win the World Series while we continue to build a sustainably good roster."

It may interest this bozo to know that a particular MLB team won 55 percent of their games over a 10-year period, starting in 1994, while appearing in zero World Series. It was the Seattle Mariners. Nobody who plays for or follows this team is as stupid as Dipoto thinks they are. There are worse things than living and dying with a cool Mariners team whose season kerplodes just steps from the finish line, until you're reminded who is calling the shots, and what it is that he thinks he is supposed to be doing.