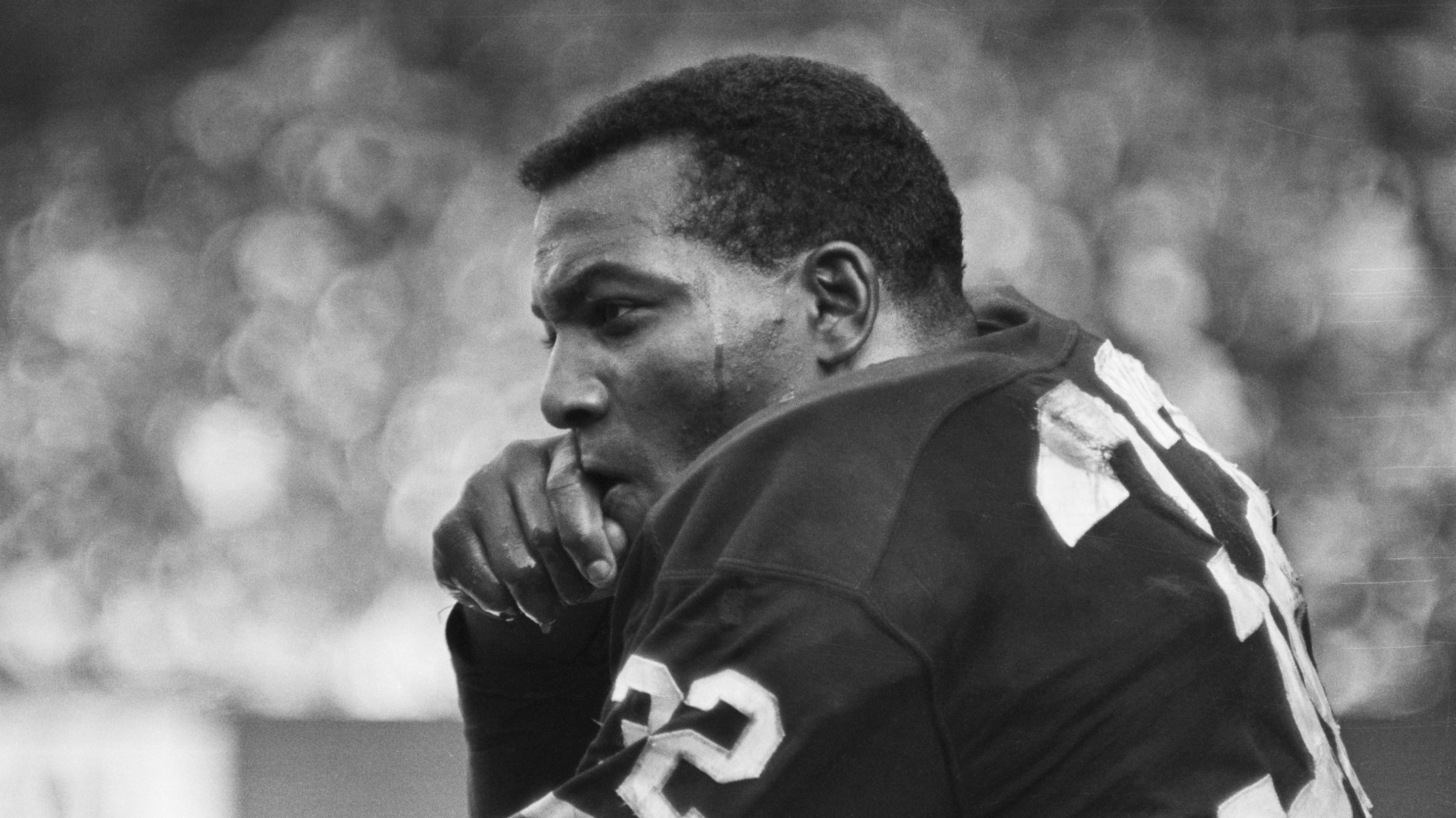

In sports, most heroes come and go, but Jim Brown remained ubiquitous. He was the NFL player who last carried the Cleveland Browns to anything resembling a championship. He also was the player who, when Browns owner Art Modell threatened to fine him for being late to training camp, decided to retire instead—and he did, at the height of his athletic prowess, gliding into a career as a Hollywood star. He was one of the first black NFL stars, one of the first black Hollywood stars, and he used this dual prominence to organize the Cleveland Summit, a.k.a. the Muhammad Ali Summit, which began as a chance for prominent black athletes to support Ali in his refusal to be drafted into the Vietnam War and became a watershed event in the history of black athletes in the United States standing together to push back against systemic racism.

It is this image, from Cleveland, that perhaps stands alone in the Brown canon. There is Ali, in front of the microphones, and right beside him is Brown, along with Bill Russell and a young Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. There were many more athletes there as well—among them Brown's former NFL teammates Sid Williams and Walter Beach—but at the Cleveland Summit, like all the most effective media events, they seemed to understand the maxim to always put your stars front and center.

Brown as Hollywood leading man. Brown as victorious Hall of Famer. Brown as activist. But also: Brown supporting Richard Nixon in 1968. Brown declining to support Colin Kaepernick. Brown visiting Donald Trump's White House. But no counter-legacy has loomed larger than Brown's long and extremely well-documented history of physical violence toward women. It stretches across four decades. It includes police records, and 911 calls, and lawsuits, and quotes given to reporters, as well as Brown admitting to hitting women in his own autobiography. In several cases, the charges were dropped or never filed because the women chose to not testify or fully cooperate with authorities, scenarios that read much differently in the light of 2023.

The way the eulogies about Brown, who died on May 18 at age 87, handled this was to declare that he and his legacy are complicated, or flawed, or far from perfect, or even American. That's a verbal trick, used by writers to explain away that which they cannot easily square. Jim Brown was a black man who grew up in segregated Georgia, and lived and worked in a deeply racist world, and it is to his immense credit that he managed to obtain some wealth, fame, and power for himself. He also hurt many people, in behavior that almost surely was enabled by that bit of wealth, fame, and power. A person obtaining, and then taking advantage of, their power is not new; this time it just so happens to involve one of history's most famous athletes.

Brown was an active football player the first documented time a woman said he had been violent to her, and she said it happened in Cleveland, where Brown was, and remains, an impossibly large star. It was July of 1965, and an 18-year-old said Brown "plied her with whiskey, slapped her face, hip and stomach and forced her to have sex relations with him on two occasions," the Associated Press reported. A Cleveland jury found Brown not guilty. That fall, Brown racked up 1,544 yards and 17 touchdowns in his ninth NFL season, his last in the league. His Browns lost in the championship game to the Green Bay Packers, but Brown still garnered copious accolades; his third MVP, as well as All-Pro and the Pro Bowl.

A few weeks after the Cleveland Summit in 1967, a Cleveland jury voted 11-1 to acquit Brown in a paternity suit brought by the same woman. A year earlier, in the summer of 1966, Browns owner Art Modell threatened to fine Brown if he didn't show up to training camp. Brown was in at the time London shooting his role in the blockbuster World War II movie The Dirty Dozen. He decided he would retire instead. He was 30 years old and had already cemented himself as a living legend.

Brown then got cast in a leading role in a film called The Split, released in 1968. That year, Brown's neighbors called the police after hearing arguing and the arriving officers found Brown's then-girlfriend, model Eva Marie Bohn-Chin "on a concrete patio 15 feet below Brown's second floor apartment," per the Pittsburgh Courier. The Courier also reported that the 22-year-old Bohn-Chin had a dislocated shoulder and head wounds. Bohn-Chin refused to testify in court against Brown; she said her injuries were caused by a fall. The Courier wrote in June that the investigation was causing "speculation" about the future of Brown's Hollywood career.

The speculation quickly fizzled. The Split came out later on that year, and Brown was cast in more films, including Ice Station Zebra, Three The Hard Way, and El Condor. In 1969, he starred in 100 Rifles opposite Raquel Welch, and their love scene is considered the first with an interracial couple in a major Hollywood film. In 1970, he confronted segregationist Georgia governor Lester Maddox while sitting next to him on The Dick Cavett Show and asked him if he was having "any problems ... from the white bigots because you did so much for the black man." Maddox quickly became enraged, gave a pile of nonsense answers, and stormed off the show, while Brown, a son of Georgia, sat by, hands in his lap, clad in a suit, allowing a slight smile.

A year later, authorities charged Brown with battery of two women, Claudia Anne Lemary and Carol Virginia Williams. A deputy Los Angeles city attorney, said at trial that Brown "knocked their heads together, beat them, threw them down the stairs, beat them again and pushed them out the front door" after they refused to perform a sex act. Lemary refused to appear in court; Williams said she fell. Both were age 22 and appeared in court with Brown before the trial, posing for smiling photos.

Brown worked steadily in Hollywood throughout the 1970s. He also spent time at the Playboy Mansion, the subject of a recent document in which two former employees, also a husband and wife couple, said they saw Brown physically abuse playmates. (When People reached out to Brown's representatives for a statement about what was alleged in the documentary, the publication did not receive a response.)

In the 1980s, Brown moved into television, making appearances in Knight Rider, CHiPs, and T.J. Hooker. In 1985, Brown was charged with rape, sexual battery, and assault after a 33-year-old woman said she was sexually assaulted by Brown after he "blackened her eye, punched her in the stomach and perforated her eardrum," the Los Angeles Times reported. Prosecutors later asked the judge to dismiss the charges, which she did, due to inconsistencies in her statements. (There's now a body of scientific research around why recalling trauma, including rape, is difficult and can leave victims with fractured memories of their own attacks.) When the woman then filed a civil suit, Brown's lawyer, Johnnie Cochran, said she was just out for money.

In 1986, Brown was arrested and charged with assaulting his fiancée. The charges were dropped when Debra Clark, age 22, told authorities that she didn't want Brown prosecuted. That same year, Brown appeared on The A-Team. In 1988, Brown founded Amer-I-Can, which worked with gang members and prisoners to teach them life skills and still exists today. A year later, in 1989, Brown's memoir was published, in which he admitted to slapping women.

In the 1990s, Brown continued to appear in TV and films, including Mars Attacks! and He Got Game, but now was just as likely to appear as himself, be it on Living Single or Between Brothers or on an NFL sideline. This is when I remember Brown the most starkly; he seemed omnipresent. To not know him would have required ignoring movies and TV and the NFL and any discussion of athlete activism. It was still a while before I even grasped how accomplished he had been as a football player. He had achieved that level of fame that is really more than fame. He felt baked into the world.

In 1999, Brown was charged with making threats against his wife and vandalism, both misdemeanors, after his wife, Monique Brown, then 25, called 911. She later told a police officer that what began as a fight with her husband about his infidelity escalated into him threatening to kill her and pummeling her car with a shovel. Monique Brown recanted her statements in court. Her husband was only convicted of the vandalism charge, and he could have avoided jail if he completed his court-ordered domestic-violence counseling as well as community service. He refused, leading to a four-month jail stint. He told reporters: “I took no deal. I’m not going to take a deal, and I’ll fight as long as I have breath in my body. That’s who I am. That’s who I’ve always been.”

The final chapter of Brown's life is mostly glory. He made every list ever compiled of the greatest football players of all time, and topped many. In 2015, Sports Illustrated ran a piece on him headlined, "Why Jim Brown Matters." (In the story, Brown said he condemned all violence and, if hit by a woman, a man should take the punch and not retaliate.) In 2016, the Browns immortalized Brown with a statue. In 2017, Brown said he did not support Colin Kaepernick kneeling, saying he did not stand by any desecration of the flag. In 2018, Brown met with Donald Trump in the White House. In 2021, Brown was one of the main characters portrayed in the film One Night in Miami, based on the fictional play that imagines one night between Ali, Brown, Malcolm X, and Sam Cooke. That same year, USA Today spoke with Debra Clark, now Debra Clark-Russell, who wrote a book about her relationship with Brown, called Everyone Has A Story.

“I think what’s helped him now from possibly being violent is age,’’ she told the publication. “He’s old. I could probably outrun him now.’’

Jim Brown realized that his prodigious gifts gave him tremendous power in our culture, and he wielded that power as he saw fit—to advance civil rights, to put an overly zealous NFL team owner in his place, to shame a segregationist politician on TV, to empower black athletes to speak up, to crash Hollywood's color barriers, and to be violent toward women for decades and suffer very few consequences. There are actions Brown took, especially early in his career, that benefited himself and millions of his fellow black Americans. And there are other actions Brown took that benefited only himself, at times leaving behind a wake of suffering. In nearly ever one of those cases, he wielded a power granted to him by football. He was just that good at football.

Perhaps that is why sportswriters can't quit the story of Jim Brown. It's too familiar: the tale of a young man who harnesses the power of sports to advance himself and then others and even the world. From a certain perspective, Brown's story can look like that myth, with all those trophies, and movie posters, and awards. It's just a matter of whose perspective you must leave out when you tell that story.

This isn't a new phenomenon. John Lennon, half of one of the greatest songwriting duos ever, was violent toward his first wife, Cynthia. Charlie Chaplin, the brilliant filmmaker who took on Hitler, also had a history of marrying extremely younger women and being cruel to his family. Even Gandhi, one of the modern fathers of the nonviolent protest movement, exhibited deeply sexist views and behavior. They, like Brown, simply became so famous and so woven into our popular culture that their star could, it seem, never be dimmed, which only added to the allure.

A few months ago, I spoke with someone who reminded me that we will not end intimate-partner violence, or really any violence, through anger or outrage at any individual. It is all just too large; systemic problems require systemic solutions. It is, like the fame of many men who perpetuate it, ubiquitous. Not listening to the Beatles or taking down a Jim Brown statue isn't going to suddenly end it. But remembering it and holding it there, in friction alongside all the good, might be one place to start.

Correction (3:21 p.m. ET): A previous version gave the wrong year for when Jim Brown retired from football. It was 1966.