Deadspin was sold to a mysterious European start-up and stripped of its staff on Monday; some ghost-ship remnant of it is now floating across the seas to Malta. The site, along with its G/O Media sister publications, entered a death spiral at the very latest in 2018, when Univision put them up for sale; they were still called "Gizmodo Media Group," then. Or maybe it was two years earlier, when a Florida jury opted into Peter Thiel's scheme to bankrupt what was then Gawker Media.

If some of the particulars are exotic, befitting that flamboyant drunkard of a company, the broad outline is dismally familiar. A once stable and profitable media shop becomes vulnerable; a series of leveraged buyouts pass it down a chain of progressively meaner and more radioactive owners, leaving it more grotesquely tumored with debt at each next stop; somebody finally liquidates it.

A big part of the GMG sites' value to Nick Denton, the company's founder, had been in how they allowed him to pursue, at rich-person scale, various self-portrayals over time: gadfly, then media visionary, then tech platform guy. In retrospect, that vanity feels nostalgic. Heavily leveraged private equity owners will never have any such use for that kind of company, or any other; they do not feel compelled to moderate their avarice with other purposes, like a thin film of oil distributing heat over a surface. They just want to squeeze. That is their entire business.

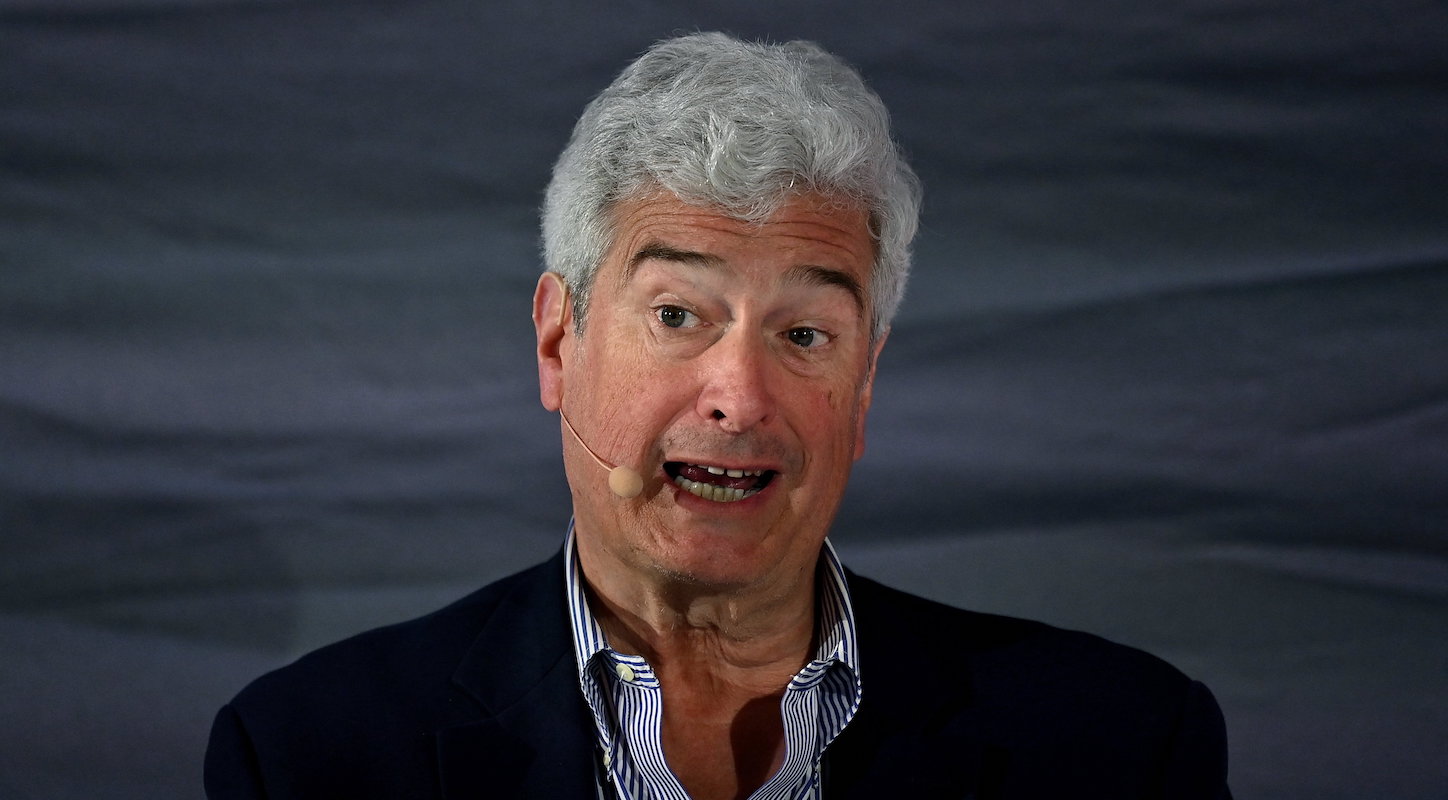

However neatly G/O Media CEO Jim Spanfeller might seem to fit the role of Deadspin's killer, he's not the arch-villain in this story. He's a symptom of what killed the site, which first had to be weakened enough that a shit-eating parasite like him could be in position to finish it off.

Still, it's worth taking stock of what exactly that looked like. For as distressed as Gizmodo Media might have been overall when Great Hill Partners acquired it in 2019 and renamed it G/O Media, Deadspin itself was at that time both a stable and enormously popular website. The death of programmatic advertising as a sustainable way to fund a media business would have come for the site's profitability eventually in just about any plausible timeline, but if any digital media publication had the legs for a long chase, Deadspin—with its huge and loyal readership and its unique demi-explicable resilience to the industry's Facebook dependency—was it. In the short and medium term, this survival and continued flourishing would have required from its executive overseers only that they leave the editorial operation alone to continue making good blogs, which would continue to be viewed by the many people who enjoyed them. We must presume that some ahuman private-equity scumbags might have taken that deal, and bled the company less visibly and more tidily; in their hands Deadspin might be just as dead today, but nobody would know the names of the people who ushered it to the grave.

That's not how it went, though. Within months of G/O Media's christening, Spanfeller had pointlessly and very publicly chased off Deadspin's editor-in-chief, Megan Greenwell, nuking the morale of a staff that had resolutely cranked out good blogs through umpteen company shakeups by then. By October of 2019—roughly six months after Great Hill's acquisition of the group of sites—Spanfeller had made the site all but totally unusable by stuffing its margins (and paragraph breaks) with browser-killing ads, including noisy autoplaying videos; his love of the latter embarrassed the company and burned an advertising deal. By November the entire staff of Deadspin had quit, Bernie Sanders was doing tweets about it, and Spanfeller (his name now virally associated with the word "herb") had exactly one writer publishing blogs on the site: G/O Media editorial director Paul Maidment, too embarrassed to put his own byline on his work, or to last more than a weekend in the gig. By the first Tuesday of November—not seven months after Spanfeller took control of Deadspin's parent company—Deadspin had gone completely dormant. More than four months elapsed before it published another blog.

By all reports the resurrected Deadspin never recovered its purchase in the online publishing industry; it certainly never came close to reclaiming its hard-won prominence in driving discussions around labor, race, and sexual violence issues in sports. Tellingly, the site relaunched with its comment section closed, to shield it from its own readers, and never reopened it. Editorially, latter-day Deadspin read like a variably well-meaning caricature of its old self, punching theatrically down at ignoramus sports fans or bonelessly scolding a vaguely invoked society-at-large where it had once chosen specific worthy targets, named them, and birddogged them relentlessly. The risks latter-day Deadspin took were strictly the accidental kind, and generally born of shoddy editorial leadership, such as when it bungled reporting the story of ESPN personality Rachel Nichols airing some racist takes about her colleague Maria Taylor and then congratulated itself for having done so, or when it rushed to heap scorn on a child for wearing blackface to a Kansas City Chiefs game based on incomplete information—namely, that nobody there had bothered to look at the other half of the kid's face—and subsequently buried itself under an avalanche of shit that it could have avoided with a seconds-long exercise of rigor. That will turn out to have been the last particularly noteworthy contribution the website ever makes to any discourse.

That was Deadspin as Jim Spanfeller pretty much single-handedly made it, starting from a slate he himself wiped nearly clean as a matter of perverse anti-principle and his signature ham-handed malevolence. I say this not to trash the people who worked there in the site's final years, but to take the measure of Spanfeller's failure at what could have been, at least in Deadspin's case, an easy job with no real duties. Presented with a simple mandate to let the site continue succeeding as long as it could and making money off that success for as long as he was interested, he opted to do this instead.

The pessimistic outlook, that the fabled "economic headwinds" of the industry were going to swamp the site eventually, only makes Spanfeller's failure all the more stark and total. If you assume that any plausible version of Deadspin might have arrived at Monday's grim evacuation and the disembodied brand's shunting along to the next vampire in line, no matter how harmoniously Spanfeller had coexisted with the staff he inherited, then all he actually did was lose however much money all that lost readership (and traffic) could have delivered, and presumably wipe out a monster share of whatever value that brand once had. On a personal level, I can't think of a single other nonfictional person whose public image is more inextricably, or deservedly, bound up with their incompetence. It's all anybody knows Jim Spanfeller for. And all he had to do was nothing at all; he couldn't even get that right. I wouldn't hire him to sweep a front porch. He'd just find a way to burn the place down.

Disclosure: The majority of the Defector staff worked at a previous version of Deadspin.