There were a number of factors that went some way toward explaining the record-setting $700 million contract that Shohei Ohtani signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers last winter. There's the inescapably abstract fact of Ohtani, a player whose only adequate scouting comparison has always been literally Babe Ruth and who as a result has always seemed more like an unusually good-natured demigod than he was like even the most elite of his peers. And there is also the contract itself, the deferral-laden format of which was either clever or cynical depending upon your perspective, but which was undeniably and utterly unlike any other free-agent contract. The deferrals in the deal were not new—the Dodgers have been pioneers in this space; they had signed Mookie Betts and Freddie Freeman to deals with significant deferred money before that, and signed Blake Snell to another just last week. But the extent to which Ohtani's money was deferred was unprecedented and, again, worked to mystify the deal in ways that went beyond those inherent to the sunny-sided godhead that signed the dotted line. The deal was awe-inspiring in all the ways you'd expect a record deal to be, but it was also complicated.

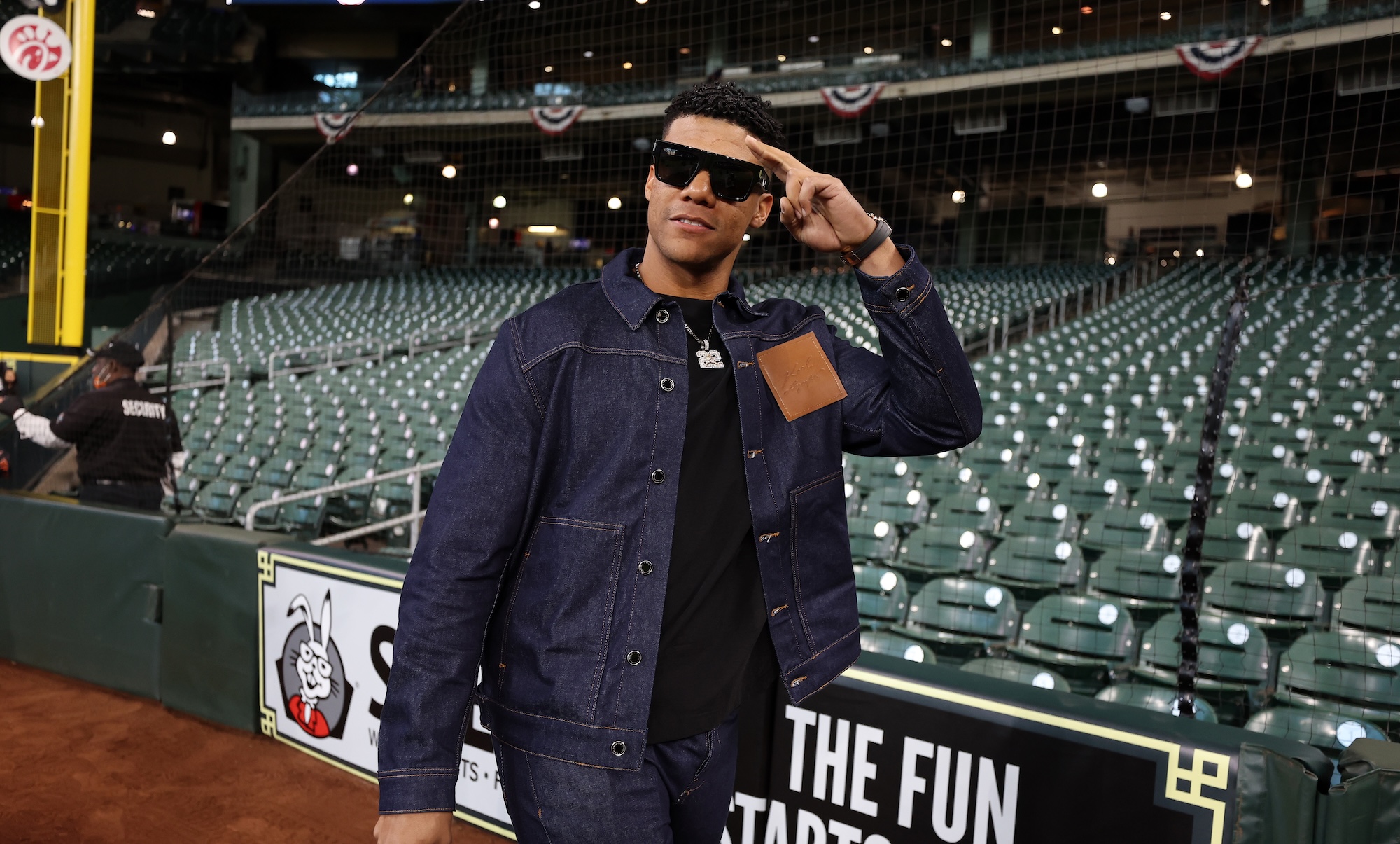

This is all worth mentioning here, in a story about the record-setting free-agent contract that Juan Soto and the New York Mets announced on Sunday night, because Soto's deal is so uncomplicated by comparison. There were some extenuating circumstances here, too—Soto's young age and broad-ranging excellence, the presence of New York's two rich and self-conscious franchises as the 26-year-old slugger's foremost suitors—but the contract itself is relatively straightforward where Ohtani's was elaborate. Which, I should note before we finally get to the paragraph with the numbers in it, does not make any of it any easier to process.

The Mets and Soto agreed to a 15-year, $765 million contract; if he doesn't opt out, escalators would take its total value above $800 million. Soto can opt out after five years, by which time he'll have earned $305 million from the Mets, including $75 million as a signing bonus. (That bonus is a record, too; Betts got $65 million from the Dodgers on his extension back in July of 2020.) It's plausible that Soto will do just that, both because he will only then be entering the back end of a prime that may only now be beginning and because the free-agent market that Soto and his agent Scott Boras just reset in such outlandish fashion will have reset itself several times over by then.

That last bit is abstract in a different way. Imagining what not just baseball but the world might be like in the decade that will begin in 2033, when Ohtani really starts getting paid, naturally makes a person consider what sort of role they might reasonably wind up playing on Immortan Joe's compound; imagining how the MLB free-agent market might look in 2029, on the other hand, mostly just makes me want to lie down for a while. It's not that baseball's next alpha free agent will automatically be in line for a million dollars more per year than Soto just got, of course. Soto's deal will undoubtedly make, say, Kyle Tucker some unknowable amount of extra money at this time next winter, but Tucker will not be signing a $900 million deal just because Soto signed this one. Tucker is a fine player, but he isn't Juan Soto; he has that in common with every young hitter in baseball over the last couple decades. The reason that Soto is getting paid like this, market forces and various other depravities and externalities aside, is that very few players in baseball history have been anywhere near as good as Juan Soto over the first six years of their career.

Even before this contract, Soto's brilliance was both monumental and hard to parse. The Nationals signed Soto out of the Dominican Republic when he was 16 years old, and he was much better, much sooner, than even the most enthusiastic evaluators expected. Soto was a star in the bigs by the time he was 19, and one of the best players on a World Series champion the year after that. The Nationals seemed somehow to have replaced Bryce Harper—who also debuted as a teenager, and who signed a then-record contract with the Phillies before the 2019 season—with a different, better version of Bryce Harper.

It didn't help them much after that World Series win in 2019, although that wasn't Soto's fault—he led the National League in average, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage during the Covid season in 2020, and was worth an astonishing 8.4 WAR by Baseball Prospectus's figuring in 2021. Washington's second generational giga-talent in a decade left town under better terms than Harper when the Nationals traded Soto—unfathomably, shamefully, and ultimately for a pretty good return—to the San Diego Padres at the deadline in 2022. The Padres, being the Padres, wound up dealing Soto to the Yankees before last season for another passel of young talent. Very few players in the sport's history has been this good, this young; none of them have moved around quite like this. The sport's most ambitious teams seemed happy to come so deliriously out of pocket in an attempt to capture some of the value he provided before they would more literally have to put a price on it when he became a free agent.

All this unprecedentedness can honestly get to be a bit much. So here is something concrete: If Soto's contract is absurd in some obvious ways and bafflingly abstracted in other more global ones, it also makes sense on the merits, beyond whatever it might do to help Mets owner Steve Cohen secure a casino/real estate deal adjacent to Citi Field that would pay for this expenditure many times over. Juan Soto has been one of the very best players in Major League Baseball more or less from the moment that he arrived in the league. If it is a challenge to accept that any player is worth that many millions of dollars over 15 years, it is much easier to assert that Soto is the sort of player with a claim on that status.

Soto is not a great defensive right fielder, although assessments of how bad he is out there have varied wildly from one year to the next. It's not that important, really, because Soto is by any measure one of the best judges of the strike zone the sport has ever seen. His .421 career on-base percentage is the best among active players and 19th all-time; his .953 OPS is the fourth-best figure in the league since he debuted and tied for 23rd all-time, just ahead of Jeff Bagwell and Mel Ott; his 769 career walks to this point in his career are much more than any player in history, with only Mickey Mantle being within 100 through their age-25 seasons. Soto doesn't swing at bad pitches and reliably punishes the juicy ones; he is disciplined and brutal as a hitter, and some comparatively minor tweaks to his offensive approach might make him even better than he is. To the extent that any sure things exist in baseball, Signing A Big Contract With The Mets And Subsequently Having A Real Bad Time is absolutely up there. But signing a player who is entering his prime, and whose scouting comp is nearly as unprecedented as Ohtani's—"Barry Bonds without the defense or baserunning" is not quite "Babe Ruth but hot," but is still not the sort of thing that gets thrown around much—is very clearly not a bad idea.

This seems like a reasonable enough place for a disclosure. As a Mets fan, I am both sentimental and an idiot. I do not expect things to work out, in part because I have seen things you people wouldn't believe: late-career Shaun Marcum facing a big-league batting order for a third time, Jason Vargas glistening and grimacing while throwing his 84th pitch in the fourth inning, Dominic Smith pursuing a fly ball in the outfield like a 1989 Chrysler LeBaron with a parking boot on it. The money of the prolific financial criminal who owns the Mets is not my money, although I am absolutely open to him giving me some of it; the most I can say for how Cohen has spent his money on this team is that he stayed doing it even after the bottom fell out of his first oafish attempt to buy his way to glory, and that it eventually worked out. It is nice, from a fan's perspective, to think that Soto, who made it to the World Series with the Yankees last year, thought that he might have had more fun with a giddily blessed Mets team that lost in the NLCS.

But also there is no need to overthink any of this. The Yankees offered Soto $760 million over 16 years, and the Mets beat it. The amount of money involved in this is abstract because it is a number too big to be held in one's brain without some discomfort, but it is also objectively absurd and pretty obviously unconscionable. At the same time, it seems more or less right. There is no such thing as business as usual for this kind of free agent, because there are not really players like Juan Soto. For every brain-breaking thing about this contract, none is stranger than this: In time, it will come to look like a bargain.