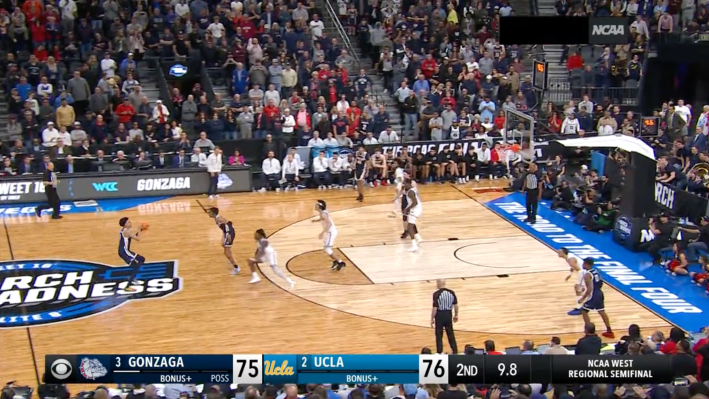

An important thing to know about Julian Strawther's incredible game-winner from the edge of the logo Thursday night, to send UCLA to hell and Gonzaga through to the Elite Eight, is that it was not quite the hero-ball heat-check that it at first seemed. It was, in fact, more or less scripted. "We practice that play," explained Gonzaga head coach Mark Few, with a little shrug, from the post-game podium. "That's Jay Wright's play, he used it at the end of the Villanova-Carolina game, the championship. I mean, that's what we call it." And in fact this shot was basically a carbon copy of the famous Villanova one: The ball-handler pushes to the top of the arc, engages with a defender, and then pitches it back to the inbounder, who catches the ball in stride against a retreating defense and pulls up for a rhythm jumper. Few's advice to Strawther, who was emphatically requesting permission to Go Legend Mode during the timeout where the play was called, was simple enough: "I just said, 'Yeah, yeah. Make it. Make it.'" And make it he did.

STRAWTHER FROM WAY DEEP

— NCAA March Madness (@MarchMadnessMBB) March 24, 2023

GONZAGA HAS THE LEAD 😱#MarchMadness @ZagMBB pic.twitter.com/jBYf4gpn4q

Permission had been given to fire away, but that doesn't mean the play necessarily calls for a damn logo shot. It's about creating a quick little scenario where a talented scorer has a moment's advantage to make a quick binary decision. "If he was closely guarded I wanted him going downhill, to see if he could get to his floater, which he's been great at all year," said Few. In other eras, this setup—a defender closing out under control against a ball-handler a good 28 feet from the basket—would be considered "closely guarded," but watch the video a couple times and you will see that Strawther only ever had eyes for the pull-up. This is not someone who was considering the floater:

It's possible Strawther still is not aware that there was a defender in good position to bother his shot. "It was a clean look," he said after the game, of the contested 28-foot three-pointer he attempted while down a point in the Sweet 16, with nine seconds left on the clock. "I got the ball and it was in my range, so I shot it." But Strawther had more than practice reps and more than extreme confidence working in his favor, here. He had experience running this same basic action, in a very similar situation, in a game against Brigham Young back in January. The Zags were down two points with 15.9 seconds on the clock and no timeouts. Strawther brought the ball up the court, slid in behind a very high screen from teammate Drew Timme, and pulled up from a couple steps behind the three-point line for the game-winner.

Few had this BYU shot in mind as he gave Strawther the green light Thursday: "I vividly—I mean, if you look back to the BYU game, he hit a very deep three, a dagger three in that game, very similar." So everyone involved felt pretty good about this shot. A hoops traditionalist would point out, correctly, that a pull-up 28-footer is still a low-percentage shot, and is a hysterically low-percentage play upon which to stake one's entire season. But here I would like to point out that this is college basketball. Most of these guys are not great; most of them are very near the ends of their basketball careers; and the more complex and intricate the demands of a play, the more likely these relative bozos are to get swallowed up and cast into chaos by the pressure of the moment.

Consider Michigan State's final possession against Kansas State, Thursday night. The Spartans were down three points with 12.5 seconds left in overtime. Tom Izzo called a timeout and drew up some action for a side-inbounds play. Low-post jostling and two high screens failed to create an immediate advantage, let alone a clean look. The first pass led to a panicky pump-fake. The second pass led to a panicky pump-fake. The third pass led to a panicky pump-fake. The fourth pass led to a panicky pump-fake. That fourth pump-faker, senior guard Tyson Walker, had no choice but to drive desperately into a crowd of defenders, where he was stripped of the ball. Michigan State didn't even get off a shot attempt, let alone a clean one. Izzo's carefully constructed ATO ended with the opponent streaking the other way and his team losing a heartbreaker. I'm gonna go ahead and guess that Izzo would give up a finger or two today to go back in time and have his team run The Jay Wright Play, for a clean 28-footer.

In most other universes, the Zags woke up today having watched Strawther's bomb clang off the rim, and in most of those universes UCLA went on to win the game. But that doesn't mean it was necessarily a lower-percentage play than something more intricately sketched, however more aesthetically appealing the latter might've been to traditionalists. It's hard to win a tournament game. It's even harder to win a tournament game when you're the underdog, and it's hardest of all to win a tournament game when you're the underdog and you're down on the scoreboard inside the game's final 10 seconds. Nothing is really supposed to work. The best thing you can do is give yourself a chance. The situation calls for heroics. Maybe the best lever you can pull is a simple play that gives a clean look to a lunatic who is itching to become a legend, from any distance.