It was a late afternoon wedding reception in a place on Martha’s Vineyard. The summer sun was starting to slide toward the gentle swells of the Sound. The groom was an assistant coach with the Boston Celtics, so there was a large contingent from the franchise. K.C. Jones was the unquestioned ambassador of the delegation.

He worked the room without noticeably working it, asking all the assembled wives and mothers to dance. I remember thinking that I was watching the application of a strain of charisma from another time, a time of smoky jazz clubs and women with orchids in their hair, a time when big band jazz was under siege by newer music, by Dizzy and the Bird, by Miles and the Trane. I watched K.C. work the room, and in my mind’s eye I could see the outline of a horn player, silhouetted against a single white spotlight, one second before he decided on the riff that would change the world. This, I thought, was the operation of Cool.

Cool, in the old, original sense, has gone out of sports. Style remains, but style is Cool accelerated until it has lost all its original properties and become something else entirely, something louder and more protean, less constant and ever-changing. Cool is a mighty river flowing in its original channels, the ones it cut out of an unforgiving landscape decades ago. Cool is a tradition, handed down like a fine piece of jewelry. Style is revolutionary. Cool is always subversive.

This is what I always saw in K.C. Jones, who passed away on Christmas Day. I saw it that day on the Vineyard, and I saw it on the night I watched him sing at his regular gig at the Parker House on Beacon Hill with the Winiker orchestra backing him up. (In my time, I have written at length about both K.C, and about the Winikers, the kings of Boston’s general-business music scene.) And I saw it every spring, when he would coach the Celtics into their annual collisions with the Hawks and the Pistons, the Rockets and, especially, the Lakers. Both he and Pat Riley shared the great gift of Cool, so very necessary while dealing with the monumental egos they put out on the floor.

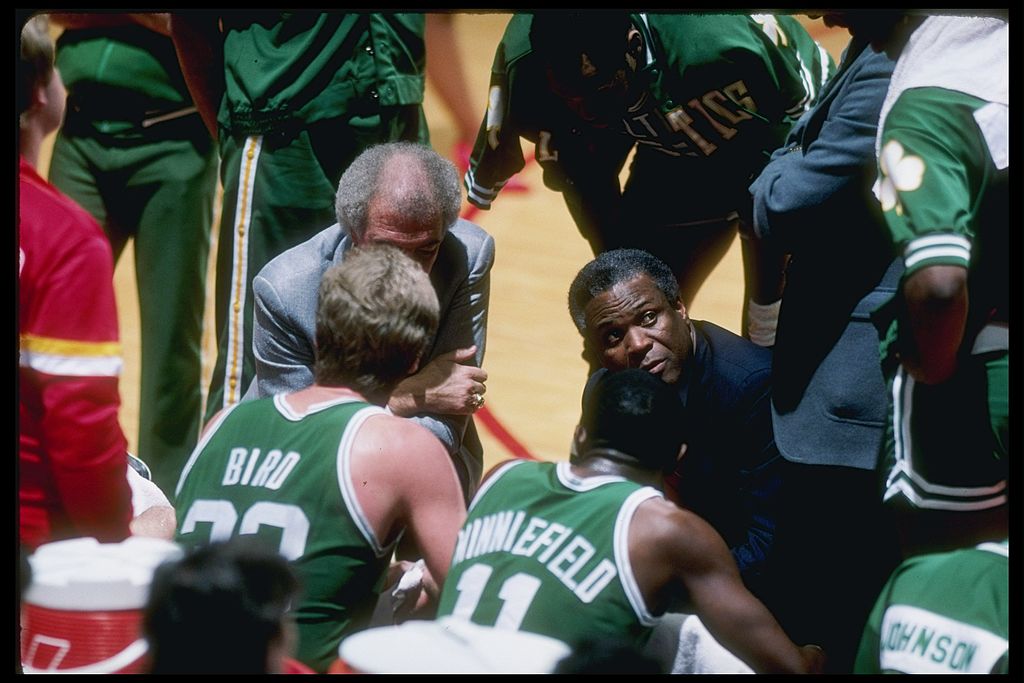

K.C. Jones had a basketball CV that surpassed even that of Bill Russell, with whom he played and won two NCAA championships at the University of San Francisco, an Olympic Gold Medal in Melbourne, and eight consecutive NBA championships with the Boston Celtics. After retiring as a player, he coached the Washington Bullets to the NBA Finals in 1975 and then, when the Larry Bird Era Celtics got so sick of being harangued by Bill Fitch that they simply quit on him during a 1983 playoff series with Milwaukee, K.C. was brought in to calm everything down, to cool everything out. He coached the team to two championships and into the Finals in four of his five seasons as its coach.

Those weeks every spring were remarkable times, basketball played at a level of intensity that matched anything I ever saw in the NFL or in a boxing ring. In my capacity as a sportswriter at the Boston Herald, it was my job to cover the opposing locker room every year, so I got to know the Hawks, Pistons, and the Lakers pretty well. But I got to watch K.C. work, too, an unruffled presence in the middle of a storm of noise in the drum-like Forum, or in the ancient, echoing caverns of the old Boston Garden. To watch him work was to see the operation of Cool as it was meant to function—to own the room without trying to do so.

He came out of Taylor, Texas, the son of an oil-worker who himself was called K.C., after the mythic railroad man. His parents split up and his mother moved herself and the children to San Francisco, where K.C. excelled at both football and basketball, and where he met another refugee from the South, Bill Russell, who’d moved there from Louisiana. K.C, was stone tough, the kind of defensive player that another team’s star would hate to see next to him at the jump circle. Having K.C. Jones guard you on the perimeter and then feed you toward Russell under the basket was like coming through a meat grinder into a woodchipper.

(He also was drafted by the Los Angeles Rams—drafted, it should be noted, by Pete Rozelle himself—with whom, in training camp, he can be said to have invented the bump-and-run defense.)

The truly dynastic Celtics of the 1960’s did more than simply win every year. They also were one of the hippest crews in all of professional sports. K.C. had his music. Russell was beyond comparison, his 1960's activism leavened with 1960's chill. Satch Sanders was quite simply the coolest man alive, always dressed sharp and with a voice that belonged on an overnight radio show somewhere in 1951. Eventually, Satch opened his own bistro, Satch’s Restaurant. Among other fine events, the club hosted the press conference at which a clearly nervous Patrick Ewing announced that he’d be attending Georgetown.

They were stars of the clubs and dives in Boston’s South End. They’d hit Wally’s Cafe and the Hi-Hat, which later would host Count Basie or Charles Mingus, when they’d tour with small combos. Duke Ellington was a regular at the Roseland Ballroom, just up Massachusetts Avenue where a shoeshine kid from Roxbury named Malcolm Little worked a stand. Later, he would go to prison for burglary and emerge as Malcolm X. At the same time, Harry Belafonte was breaking wide with calypso music, Boston’s answer was a singer who went by "The Charmer," a graduate of Boston English High School named Louis Eugene Wolcott, who underwent a similar transition, abandoned music, and came out of it calling himself Louis Farrakhan. This was the milieu in which the African American players on those Celtics teams immersed themselves as a sanctuary against the virulent racism that marked so much of the rest of the city.

Moreover, the Celtics of those days were surprisingly enlightened in many areas. They were the first NBA team to integrate, the first NBA to start five African American players, the first team to hire an African American coach, the first team to hire two of them, and then the first team to hire three. Tommy Heinsohn, who also died recently, was president of the NBA Players Association. In 1964, as part of a fight for pension rights, Heinsohn organized a wildcat job action before that year’s All-Star Game, he and the players stayed in the locker room until the owners agreed to submit a pension plan the next day. Meanwhile, Russell took a high profile role as the civil rights movement gathered momentum. He was in the crowd at the March on Washington. He went to Mississippi in the aftermath of the murder of Medgar Evers, He joined other black athletes to line up behind Muhammad Ali when the champ refused induction into the armed forces. Most recently, at 83, he took a knee in support of Colin Kaepernick. Even Bob Cousy, the superstar point guard who dished passes to K.C. and Russell in the dynasty years, once told author Tom Callahan, "If I were black, I'd be H. Rap Brown. No, I'd be dead." That was the Celtics of the era. They were lordly and smooth. They were cool because they never tried to be.

Watching K.C. Jones sing at the Parker House, or watching him dance as night fell slowly over the Atlantic, was to see a form of Cool that was already fading, fading like the evening sun into the sea.