Defector has partnered with Baseball Prospectus to bring you a taste of their work. They write good shit that we think you’ll like. If you do like it, we encourage you to check out their site and subscribe.

This story was originally published at Baseball Prospectus on February 23.

I adore talking shop. I know, it’s a habit so ugly that even Adam Smith warned against it. But if there’s one thing I love as much as writing, it’s sitting around with a beer and talking about writing: the secrets of the craft, the horrors of editing, and the people who transform themselves into brands, especially the ones who succeed at it. It’s gossip, it’s self-justification, but there’s something exceedingly satisfying about it. Writing is a nebulous thing; the pieces it felt like you wrote well never do well, and there’s no scoreboard. Talking it through with someone legitimizes that work, gives it perspective.

This is to say that as incomprehensible as it was for former Seattle Mariners President and CEO Kevin Mather to make 45 minutes of public remarks on subjects that really shouldn’t have been made public, it also makes a lot of sense. Yes, Mather ruined his reputation and damaged the reputation of his company, bringing down the wrath of almost every party from fans to players to the player’s union to Rob Manfred himself, all for the sake of a bunch of septuagenarian Rotarians. But let’s not underestimate the value of the latter. For the insulated upper class, the morning service club plays an important role: It’s where one gets to be among one’s own kind, among people who truly understand how heavy the crown is.

It’s a club. It’s a place to talk shop, to ground the difficult, largely behind-the-scenes work that goes into being an executive. And it feels good to talk that process through, in a world separate from the journalists and snoops. Fifty years ago Bowie Kuhn tried to excommunicate Jim Bouton for violating the sanctity of the clubhouse, and Kevin Mather was operating under the same, assumed aura of protection. He was safe among his own, the people who have to deal with running a business. After all, this wasn’t even the first time he’d spoken at the club; it was just the first time a volunteer thought to toss it up on YouTube.

The problem isn’t that Kevin Mather is a terrible CEO, a bumbling idiot who showed his ass in front of the world for charity. The problem is that Kevin Mather is an extremely successful and talented CEO, who showed his ass because he lost touch with the idea that showing ass is all that bad.

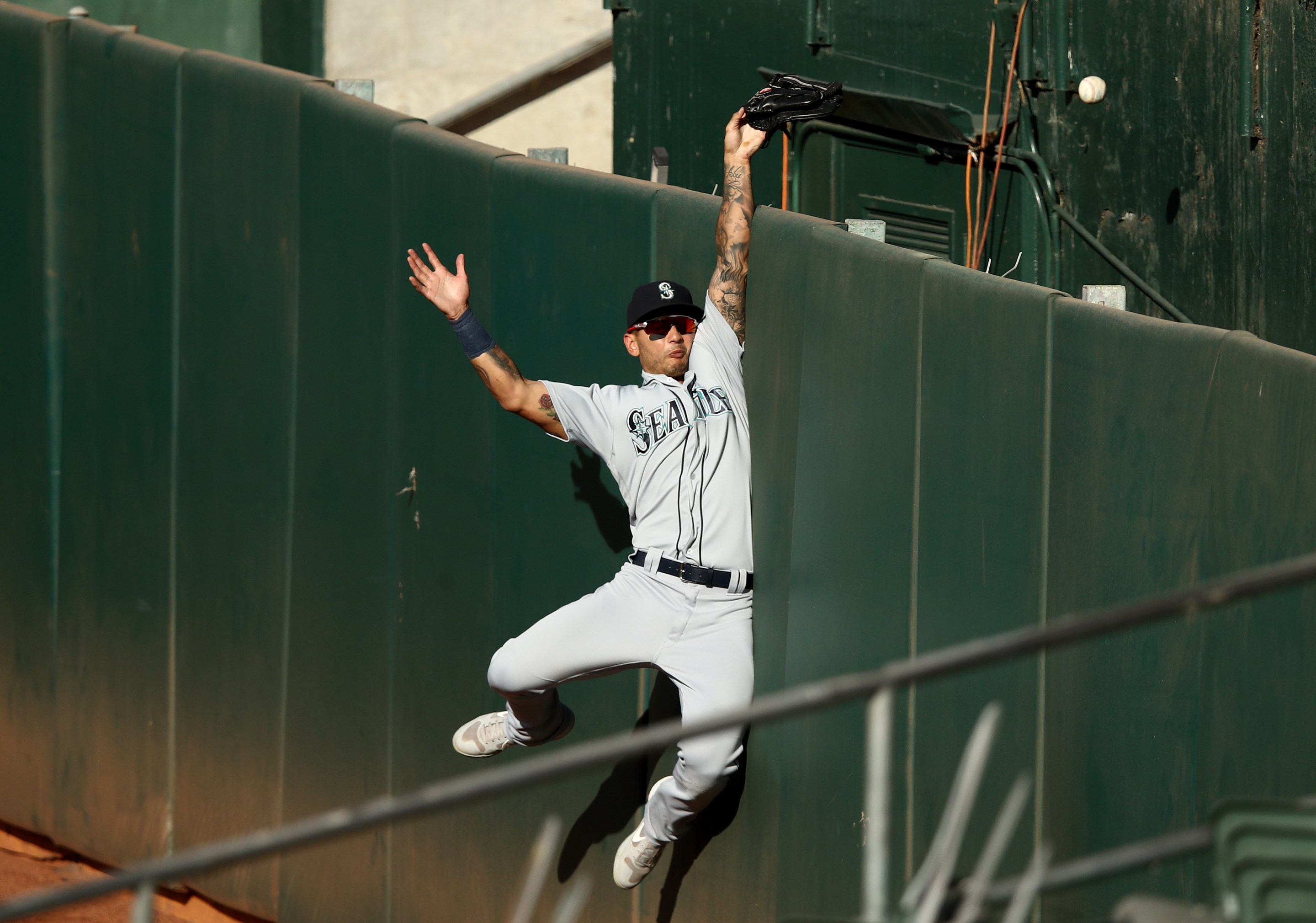

There will be repercussions, lots of them. Julio Rodríguez, criticized for (at the age of 20) speaking English with suboptimal proficiency (a claim disputed by the Athletic), openly subtweeted his boss’s boss’s boss. Kyle Seager's wife Julie, upon learning that Mather had no interest in retaining the team’s best player after his contract expires, no matter what the price, asked if she should put their home on the market. Jarred Kelenic, whose last name Mather couldn’t pronounce, was pressured to sign a team-friendly contract and will likely test free agency as soon as the next CBA makes it humanly possible. The CBA itself is in renewed jeopardy after Mather committed the only punishable crime of gaming service time by saying “I game service time.” Memories resurfaced of Mather’s past settlements; one related to the firing of Lorena Martin and others dealing with sexual harassment suits that not only saw him remain with the team, but receive a promotion afterward.

There will be repercussions, but they will probably not be meaningful to the Seattle Mariners. Kevin Mather could not escape his fate, but there will be a different Kevin Mather to take his place, as anonymous as his predecessor once was. Because the organization doesn’t care. They are the least successful MLB franchise of the 21st century in terms of on-field performance, and one of the more successful ones in terms of the only performance that matters to them. And why not? They enjoy a tax-friendly, top-tier ballpark (albeit in a part of town Mather chose to denigrate). They make their home in one of the most affluent cities in the nation. They own their own television company, broadcasting not only their own games but the new hockey team’s, and make a handsome profit from it. More than any other franchise, they’ve proven that winning and profitability are barely in view of each other.

Having discarded the last ambitions of winning with the Canó-Cruz-Seager-Félix core passed down by former general manager Jack Zduriencik, management has swung into the typical rebuilding narrative so common in the modern game. And for several years, they succeeded at it; once owners of one of the worst farm systems in baseball, BP ranks their current collection second overall, with Rodríguez and Kelenic headlining a core of talented and mostly healthy young players. After finishing last year at 27-33, the franchise had built up its first swell of recognizable momentum since the Ackley/Smoak/Montero years. And yet, instead, the team’s 2021 additions for most of the winter amounted to Doosan Bears ace Chris Flexen and waived reliever Keynan Middleton. James Paxton did sign a one-year, $8.5 million deal, but only after he came down from an earlier asking price of $12 million. Seattle’s payroll remains 25th in the league.

This is simply a mark of Mather’s business acumen. Did he damage his relationship with the team’s pair of top-10 overall prospects? Sure, but when winning doesn’t matter, talent doesn’t matter. Kelenic and Rodríguez are more valuable to the team now, as unwilling marketing employees and hype targets, than they will be in 2025 as 30-home run hitters with arbitration battles to conquer.

It’s ironic that these revelations surfaced from a Rotary club meeting, beyond the insulation of the audience themselves. The purpose of the Rotarians is to provide community service. That service, like all philanthropy, can often be selective or self-serving, but the intentions are there. Baseball teams are also supposed to provide a community service, even if the guidelines for doing so are unwritten. Almost all receive public funding, and lobby for special treatment on the grounds that their product is indispensable and valuable. Every baseball stadium, particularly in the planning stages, is presented as a communal space, a public green where you can’t technically walk on the green.

And yet the denizens of Pittsburgh can tell you how community-driven a sports team can be. Elected officials have often gerrymandered and financed their way into their own level of insulation from public opinion, but they do still have to be elected. A pro sports owner serves a life term, if they so wish. The city of Seattle has spent its forty-odd years cursed with a series of owners either inept (Danny Kaye & company), miserly (George Argyros), or pernicious (Stanton et al.). The pinnacle of Mariners ownership arrived when the team was helmed by Hiroshi Yamauchi, a man utterly indifferent toward the game. To serve the community, a baseball team must act on one primary promise: It must try to win. The Mariners are not alone in failing to fulfill that obligation; they’re just the worst, today, at hiding it.

In a Monday afternoon press conference with reporters, Seattle Mariners principal owner and Acting Mather John Stanton hammered on the theme that his former employee’s statements somehow didn’t reflect the organization, despite the fact that he literally led the organization. As Seattle Times reporter Ryan Divish asked Stanton how we could possibly believe that, the owner answered: “I would encourage you to think of an organization as more than one or two leaders … each of your organizations is a reflection of both the people who do the work as well as the leaders.” It’s a rare example of constructing, rather than piercing, the corporate veil, in an attempt to diffuse the blow to the team’s reputation. He’s technically not wrong. The Seattle Mariners are more than just the voice of their leaders, but also more than the work. They’re also the collection of values and incentives that elevate the leaders who use those voices, the shadow of all those old repercussions, and what has been learned from them.

Peppered through his answers was a continual refrain: “This is not who we are.” That we should value action over (these particular) words. The problem is that the actions and the words weren’t in conflict, in this case. The team really is tanking. They really are manipulating service time. They really are making their employees park across the tracks. They really are saying racist things. And they’re not going to stop doing them, because they weren’t doing it to be evil. They were doing it because they follow incentives the way rats hunt down cheese in the maze. Those incentives haven’t changed, including the golden one: “Don’t get caught.”

Apologies like these never contain specifics, because avoiding specifics is what they teach you in law school. The organization just went through this upheaval for failing to meet a standard, after all. Why would you voluntarily create more standards that you’ll only have to meet later? Transparency is for suckers, in both business and government. We’re saved only by the fact that people can’t help but be suckers, once in a while.

But when you’re trying to establish who you really are, you can’t do it by holding your cards to the vest. Unlike writing, and unlike managing, sports have scoreboards. They have direct measurements of success and failure, tidy and quantifiable. The arrangement between fan and team is that we get to see the scoreboard, and that the results are objective. And for that reason, Kevin Mather’s accidental confession is exactly what the Seattle Mariners are, until they can prove otherwise. That’s what the record says. And they’ll remain that way as long as they maintain the corporate priorities that they’ve demonstrated and loyally adhered to over every step of the current ownership regime. The only change we can accept at face value is that the next CEO will be more of a Kiwanis Club guy.

Kevin Mather is not unemployed because he did something wrong; he never would have become team president if that were the case. He’s unemployed because he told the truth where others would hear. In order to survive, Major League Baseball needs its lies. It needs the fans to believe that there is more to the game than just corporations struggling to maximize profit, that the box score means something different than playing fantasy sports with stocks. It needs to reward its fans for the effort of their devotion, to maintain the fraying division between “fan” and “consumer.” Kevin Mather is a product of Seattle Mariners culture, but the Mariners are a product of MLB culture. At some point, the league needs to stop trying to keep their truths from becoming public, and start trying to make them less offensive.