The first time I saw a spotted lanternfly, I was enchanted by it. It was just a nymph, I know now, shaped like a beetle with model-length legs. It fell from the tree above us and scurried around our big beer steins. It was black with white spots. It looked like it was ready to go to a fancy party. Near the collar of its sack-dress body was a beautiful red stripe. My friend Quigley smashed it with a napkin before I could even finish admiring it.

This seemed harsh to me. We were outside, in the bugs' home! Was this not our fault? Could the beautiful bug have simply been brushed to the ground? More than that, it was out of character. What did this bug do to my (very kind) friend to deserve such violence?

I was so naive back then; I knew so little. Now I am hardened. I have grown. I know that the spotted lanternfly is my enemy, and that I must vanquish it.

The spotted lanternfly was first spotted in Pennsylvania (where I now live) in 2014. Since then, it has migrated to six other states. Most recently, it has established itself in North Carolina. It is native to China, extremely invasive, and an absolute menace.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture's Animal and Plant Inspection Service, the lanternfly is hellbent on destroying: almonds, apples, apricots, cherries, grapes, hops, maple trees, nectarines, oak trees, peaches, pine trees, plums, poplar trees, sycamore trees, walnut trees, and willow trees.

That's too many nice things! This one bug is going to kill cherries AND beer? Not on my watch it isn't!

No. Together, we must kill them. Here's what a document released by Penn State's Agricultural Science advises:

"If you find any life stage of spotted lanternfly in a municipality where it is known to exist, you should try to destroy it. This insect is considered a threat to some crops and many people are working to try to prevent it from spreading. Each female will lay up to 100 or more eggs in fall, so by destroying even one female, you are reducing the potential population for the future."

You must destroy them! Swat them! Smush them! You might think you can cheat this method by using fly tape. I considered this since one of my neighbors has fly tape on their tree and they are capturing so many lanternflies. But fly tape can also hurt other animals and is discouraged by wildlife conservationists. So you have to use the other objects at your disposal. Shoes work. So do flyswatters and garden trowels and notebooks. Just about anything will do.

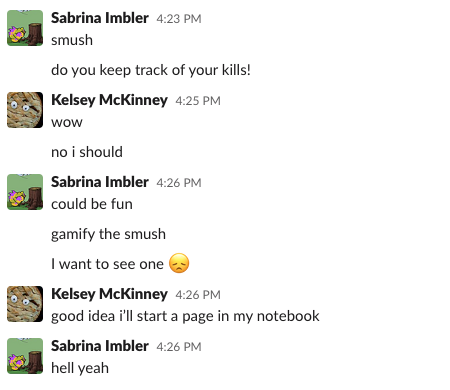

Earlier this summer, I messaged my colleague and Creaturefector expert Sabrina Imbler to share with them my new part-time job of killing lanternflies. Sabrina had a wonderful and fun idea:

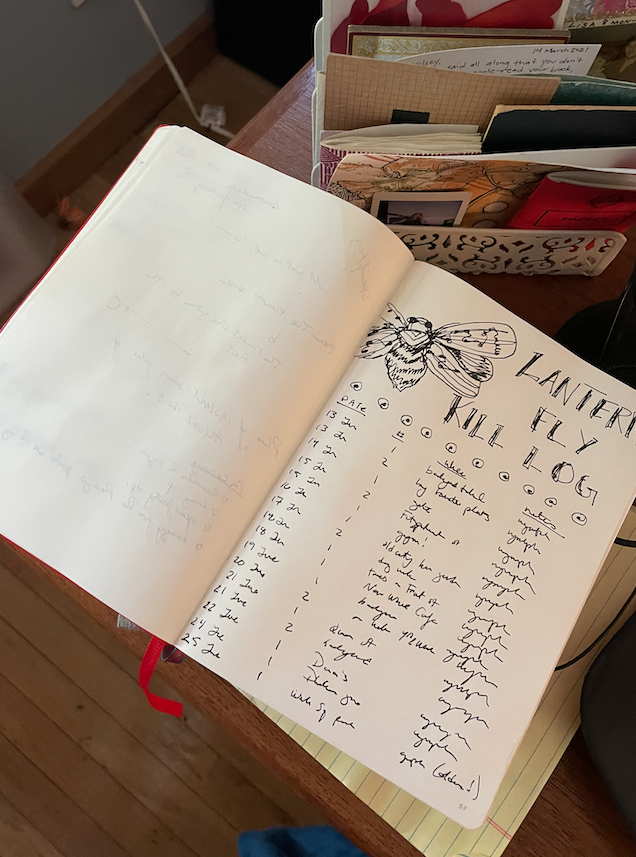

This is why I began in my notebook a Lanternfly Kill Log to "gamify the smush." And let me tell you, it rules.

I started my kill log on June 13 and have now killed over 50 lanternflies! Look at my log:

As you can see, I've decided to track the date, number of flies, location of kill, and what stage of development the fly was in. You can see that from June 13 to June 24, I was only killing nymphs. On June 25, I killed my first later-stage nymph (you can tell because when the nymphs get older, they begin to have red on them).

Last night, I went to grab a beer with a new friend and there on the table an adult lanternfly (my first of the season) dared to land near my fries. The gall! I smushed it with the bottom of my beer can. I was excited. I wrote the location and type in my iPhone so that I wouldn't forget to add it to my kill log when I got home. Gamifying the smush has nullified any guilt I maintained over killing these (actually quite pretty) bugs. They have to be smushed to save the native plants around me, but they also have to be smushed so that they can be added to my tally. The numbers must go up.

The kill log has given me a goal for walking my dog, and a reason to go outside when it is so hot it feels like I could melt. If you live in one of the nine East Coast states where the spotted lanternfly is threatening to take over, please join my cause. Together, we can win.

STOP LANTERNFLY pic.twitter.com/0FDY0awJZm

— kelsey mckinney (@mckinneykelsey) July 9, 2022