There’s something in Killers of the Flower Moon that I can’t stop thinking about, and that is Gene Jones. Jones, the character actor most known for playing the gas station attendant in No Country For Old Men, doesn’t play a noteworthy character in this film; there’s no great line he has or action set piece he appears in. He is notable just for showing up—first as simply himself, Pitts Beaty, the money manager and banker for the Osage people, the man who gets to decide how and when the Osage can have their own money. Later in the film, when the Ku Klux Klan has a parade through the city, he is there in the center of it, robed up and all smiles. He's there warning William Hale (Robert De Niro) that his murder campaign against the Osage is starting to get a little too obvious. He’s there again, just for a few frames, sitting on the jury of Hale’s peers that is expected to judge him for his crimes. Nothing about the film lends any obvious significance to Jones's character, but his journey through the action is still there for you to see. He's just waiting there, waiting for you to notice him, and the crushing machinations of white supremacy personified, on your own.

Martin Scorsese is good at showing how easily the subtle hand of history can make our own feelings or input beside the point. The power of that hand is often felt through the rises and falls of his characters. It's there in the crushing formalities and politics of The Age Of Innocence, and when The Irishman's Russell Bufalino leans close to Frank Sheeran to whisper, "If they can whack a president, they can whack a president of a union. You know it, and I know it." Who the “they” is doesn’t matter. It never matters. History just falls on these characters as they chase immortality through any means, good and bad. Killers of the Flower Moon is certainly about terrible people, but it’s also about the way evil functions in real life. Evil is not enacted by a bunch of masterminds or soulless demons who come like the wolf to blow your house down. It instead arrives in the form of unthinkable contradictions, carried by people who not only live amongst those they destroy, but befriend them, sleep in their beds, and care for them. And yes, they can find a love for you while still never seeing you as a full, equal human being.

The white men in Killers of the Flower Moon are, to put it kindly, doofuses—from Elmer Fudd-ass Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), to his overly folksy uncle Hale, to the collection of dimwits they hire for their dirty work. These aren’t men smart enough to get away with crime, and their actions are a pretty open secret around town. The trick is that there’s no one around to convict them of anything. They are less evil or naturally bad than they are slaves to their greed and lust, and their unwillingness to interrogate their behavior leads to bloody attempts to justify it. These kinds of characters are Scorsese’s bread and butter. Plenty have criticized him over the years for putting his audiences inside the minds of monsters and thus normalizing them, but that's never been his goal. In Killers of the Flower Moon, Scorsese once again trains his eye on despicable men not to excuse or glorify them, but to show us how easy the world and weight of history makes it for their rot to bloom.

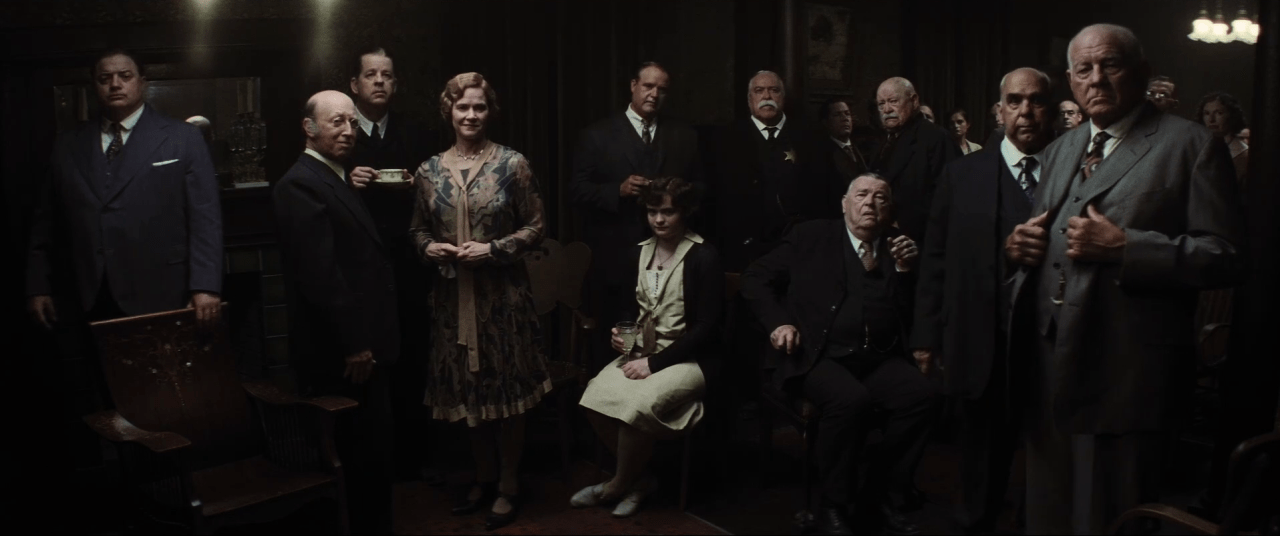

In Killers of the Flower Moon, Scorsese is ultimately concerned with systems, both visible and invisible. Hale alludes to being a Mason, and at one point watches newsreel footage of the Tulsa race riots, not far from his own location. There’s also a scene near the end of the film, where Burkhart walks into a room full of the town’s most powerful white society, all of them arranged and lit in such a way that they take on the aura of devils. None of these scenes announce anything specific to the movie, but they point to a lineage of abuse and power in which these people are simply new cogs. When Hale talks to Burkhart about what awaits the Osage, he speaks of it in terms of inevitability rather than active genocide and ethnic cleansing. If something is destined to happen, as it has always happened and will always happen, then why shouldn't it be them to carry it out?

Critics have raised justifiable concerns about how the movie doesn’t spend enough time with the Osage people, particularly Mollie (Lily Gladstone), Burkhart's wife who eventually compels the FBI to investigate the murders taking place. She has the hardest job in the film, as she has to convey a lot of conflicting feelings sometimes with just the look on her face. This is a thing Scorsese does a lot, highlighting the judgmental eyes of the innocent in the midst of corruption around them. I don’t disagree with this criticism, but I will say that my desire to see more of her is about Gladstone's performance and not the movie doing something wrong. A scene I can’t get out of my head is one where Mollie is in church talking to a priest about her feeling that someone is trying to kill her. When the priest asks who it is, she can’t bring herself to say, but her face makes it clear that she knows exactly who it is. The movie lives in that tension, that certainty in your gut that you can’t say out loud because doing so would upend your entire world. She brings all of that out with just her face, and that does more for her character than any sort of speech or confrontation could. It’s natural to be skeptical about a white filmmaker’s focus on a white perspective in a film like this. Such a point of view is required, though, if the aim is to show how the machinery of American racism and plunder is actually constructed, and to force the audience to sit uncomfortably close to that construction. Killers of the Flower Moon is not a perfect film, and Scorsese is not a perfect filmmaker, but his aim is true.

I thought a lot about Taxi Driver watching Killers of the Flower Moon. They’re very different movies, but in comparison they can offer plenty of insight into the evolution of Scorsese's filmmaking. The vibrance and salaciousness that made Travis Bickle such a captivating character gives way to much more banal but equally disturbing depictions of madness. Killers is Scorsese at his most restrained; you can feel him trying to be respectful of the Osage and not overly exploit and glorify their murders. The violence is filmed tragically, graphic enough to make an audience feel that pain, but not gratuitously. The film's perspective on the perpetrators as opposed to the perpetrated against will certainly remain divisive, as will an ending that is meant to indict the true-crime industry and maybe the filmmakers themselves. But what ultimately shines through, as it so often does in Scorsese's films, is his answer to everyone who will watch this film and find themselves asking, "How could this happen?" as they leave the theater. The answer is "pretty easily actually," and much like Jones's Pitts Beaty character, it's always right there in plain sight.