I'm not going to look this up, but I assume there have been far fewer found-footage-style films in the romantic comedy genre than there've been in horror. We could fix that, by God. Heaven knows there are enough moving-picture content mills out there. We could hire up Rachel McAdams and Matthew McConaughey and stitch together convincing enough handheld clips of the two of them meeting-cute at a destination wedding in Belize. She is the misfit career-oriented maid of honor and he is, I don't know, a local expat diving instructor and a cynical brokenhearted divorcé; at first they hate each other and then—here's the twist that'll feature in trailers—she heroically saves him from being eaten by sharks (within close filming distance of the chartered boat, of course). A bond develops between them, which is captured for posterity by persistent wedding photographers and various cell phone-wielding tourists. We'd name him Doyle and call the movie Doyle's Delight, which is also the name of Belize's tallest mountain. No one is allowed to steal this idea!

None of the challenges that make found-footage at best a long-shot of a storytelling gimmick for the powerhouse Doyle's Delight project specifically and for that otherwise shriveling genre more generally are any less true when ported over to horror, where found-footage is by now something like a standard framework. Once upon a time, maybe, the found-footage format was about leaning into the subjective camera and forcing viewers into an intense first-person experience. Nowadays it's what you do in place of thoughtful cinematography, the cheapest toy in the overpopulated and highly unsanitary sandbox of a direct-to-streaming-ass genre. It's been 17 years since Paranormal Activity accelerated the shift from a stressful subjective view to a voyeuristic objective one, coincidental to a resurgence in horror cinema that delights unreservedly in the sadistic thrill of watching other people be terrorized, if not brutalized. Found-footage no longer requires the Blair Witch Project's tricky hoop-jumping to integrate the psychology of the person still holding the camera, much less any particularly thoughtful narrative justification. Audiences accept it and forget it, and moviemakers understand this going in.

The point is that found-footage (and its related gimmicks, screenlife and psuedo-documentary) is now something like the opposite of creative filmmaking, at least in horror. If you are hoping that your film will be received as something new and fresh and interesting, the worst signal you can send short of hiring J.J. Abrams to direct it is to force it into a found-footage presentation. The choice all but announces a lack of inspiration; the work that your actors and crew will have to do to overcome that deficit is by and large beyond the modest abilities of the effects-mad goofballs and vaguely recognizable character-actor Guys who turn up for low-budget horror filmmaking. The savings it delivers in terms of budget or storytelling come with a load of crushing, dreary creative debt.

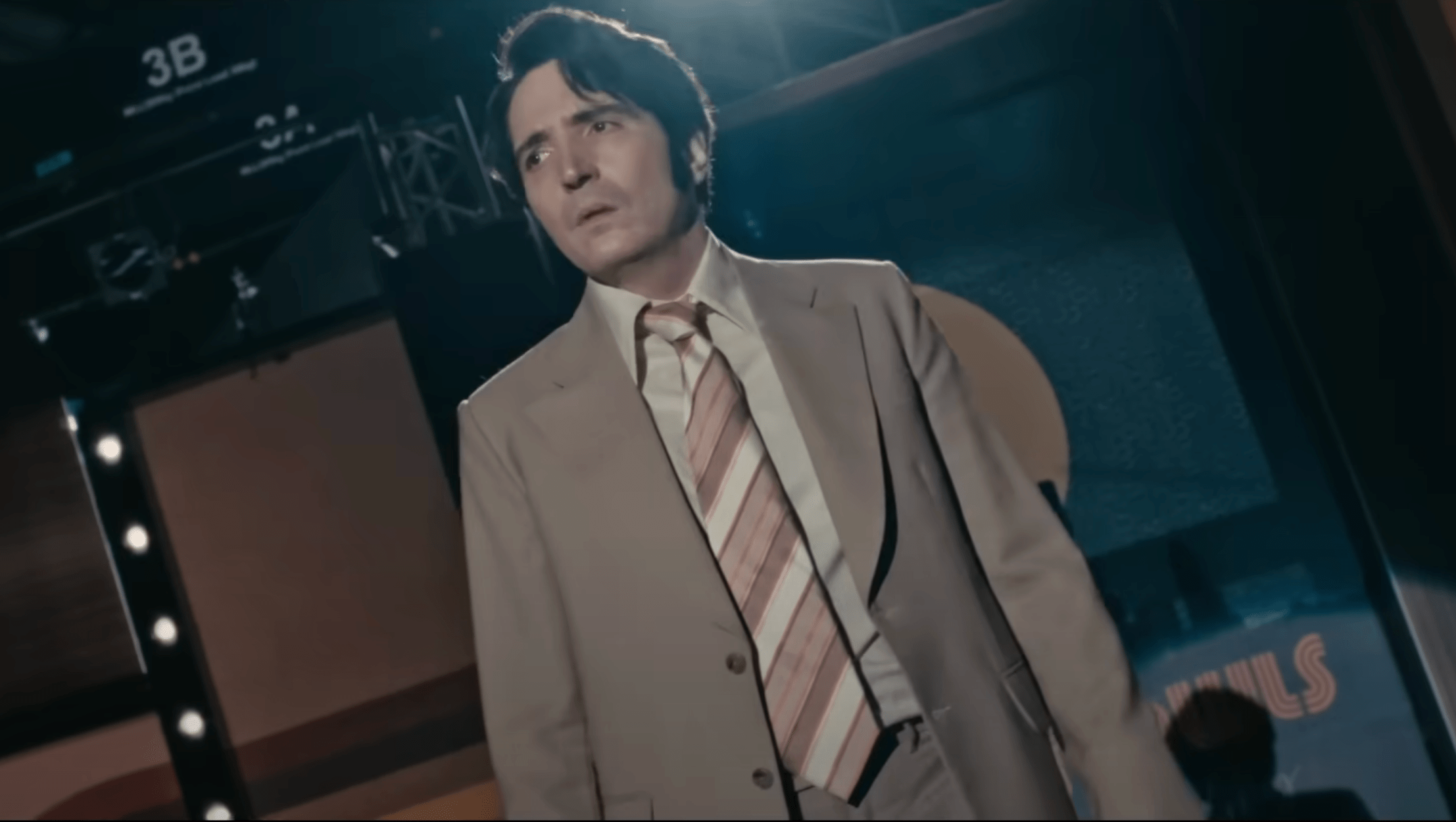

The horror streaming service Shudder is currently giving a push to a movie called Late Night with the Devil, which was made in 2023 and features dependable Weird Little Guy character actor David Dastmalchian, in a rare starring role. The film is set in the 1970s; Dastmalchian plays entertainer Jack Delroy, the down-on-his-luck host of Night Owls with Jack Delroy, an underdog late-night competitor to The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. Delroy, in need of something like a professional miracle, is kicking off the 1977 autumn sweeps with an over-the-top Halloween-themed show, which the movie sort of flimsily suggests has a chance in hell of generating a ratings bonanza. The climax of the night's lineup is expected to be an interview with a controversial parapsychologist, accompanied by an adolescent girl who is supposed to be possessed by a demon. It does not go well.

There's stuff to groan about in that top-line description, but I stand before you today to defend with great passion the idea of a movie set at the cusp of Satanic panic, featuring a desperate sleazy entertainer, played by a very enjoyable Weird Little Guy character actor, and chronicling a single night of deranged wee-hours 1970s television. The boldly colored and oddly angled post-hippie aesthetic decadence of the disco era; the fabulously flimsy smoke-and-mirrors ingenuity of even mid-tier pre-cable television production; the titillated insanity of American Satanic panic; and the squirmy affectations of David Dastmalchian, an underrated but reliable scene-stealer who is charged here with holding the movie's narrative center. To me that's a combination of things that almost cannot help but work.

Almost! Imagine the anguished sound a person makes when they look out their car window and see the pancaked carcass of their own beloved pet on the side of the road, and then dial the volume down only slightly to account for a sleeping toddler in the back seat, and you will have approximately the groan that gushed out of me when it became clear, during the movie's too-long pre-title introduction, that Late Night with the Devil is presented as archival footage. Here we have a solution in search of a problem: A presentation that assumes, wrongly, that asking the question but what if it was real will facilitate rather than distract from the audience's suspension of disbelief.

The artistic narrowing that follows from that choice sorely burdens the film. How could it not! The thing that a movie like this ought to be, more than anything else, is weird. The disco era was a weird time, man! Satanic panic was weird; occultists are weird. The film's star is weird; seeming weird is something very like his job. I cannot overemphasize how surreal and (yes) weird the experience was, even in the 1980s, of staying up in front of a crappy television after the point when certain networks started just shutting down for the night. It's worth capturing all of that weirdness together in a movie, of magnifying it and spinning it a little more frantically and allowing it to spit out something even weirder. The task deserves moviemaking choices of commensurate weirdness: strange timing, odd angles, shifting and unreliable perspectives, Dario Argento-esque lighting, an extremely fucked-up original score. Movie stuff, basically, as much of it as the film can hold. Opting instead to restrict your choices to those with fidelity to bog-standard talk-show mise en scène and backstage handheld documentary is fucking criminal! I am swearing out an arrest warrant as I type this!

Not everything in Late Night with the Devil fails. Dastmalchian is great, even in instances where the screenplay is asking him to portray emotions that are howlingly out of place both in a movie with this basic premise and on a live late-night talk show. Night Owls is fun for otherwise looking and feeling true enough, particularly during an early montage sequence of some of the show's historical high points. I would've watched this show—hell, I'd watch it today. They should make Night Owls with David Dastmalchian and just have him do in-character goofs on stage with third-tier guests; there were brief moments in the first half of Late Night with the Devil where the idea of a couple hours of watching Dastmalchian-as-Delroy charm a studio audience seemed like a fine way to spend the past-bedtime portion of a Saturday night.

But entirely too much of the movie is told in black-and-white handheld documentary-style backstage footage, with a subjective camera that frankly makes no sense at all, especially given the content of the conversations it captures. The parts of the movie told in color via the live television feed are much livelier, if also bogged down by the same broader lack of original ideas that led to the use of the found-footage format in the first place. There's a very clever sequence just shy of the film's drearily effects-laden action climax where the film actively undercuts certain elements of the plot that it had frankly been working way too hard to sell in the first place. An intolerable asshole skeptic invited onto Delroy's Halloween-themed show for no earthly reason uses hypnotism to puncture the highlight spectacle of an earlier live encounter with a demon. He uses stagecraft and a pocket watch to gain mind control over not just his half-willing studio participant but the live audience and the viewers at home, including you, sitting there on your couch.

The execution of this gambit is more explicit than it should've been, and hints at a better, different direction that the film could've pursued. As it is, the moment is ultimately used for an entirely predictable plot development, but it at least expresses a rare moment of by-God inspiration in a movie that otherwise stopped thinking for itself immediately after landing on the late-night setting.

That's what found-footage will do to a motherfucker: Instead of enjoying the full breadth of style and storytelling options that this art form makes possible, the makers of Late Night with the Devil stuck themselves with what was plausible in the context of archival television footage. What if this were real? OK, yes, sure, but I have a better question, paraphrased from a quote from Jack Nicholson in Vivian Kubrick's The Making of The Shining: Wouldn't it be better to be interesting?