I was in second grade when Lefty Driesell showed up in College Park, Md., to coach at the University of Maryland. I remember the bumper stickers repeating his goal upon arrival to turn the basketball program into the “UCLA of the East.”

Times were dreadful for sports fans in the D.C. market when he arrived. The NFL team hadn’t had a winning season in 13 years. The Senators were a perennial second-division team on the verge of leaving town. The Bullets were still in Baltimore and the Capitals wouldn’t be around for another five years, and John Thompson hadn’t taken over Georgetown yet. But Driesell, with his southern-Virginia drawl and smile, made everybody believe. He’d go on to become the first college coach to win 100 games at four different schools: Davidson, Maryland, James Madison, and Georgia State. But it’s his 17-year run at Maryland that made him famous nationally and cherished locally.

Driesell, who died on Saturday at 92 years old, didn’t come close to living up to the bumper sticker. His Maryland teams never got past a regional semifinal in the NCAA tournament. But hell if Lefty and his Terrapins didn’t always seem to be having more fun than stodgy John Wooden and his perennial champion Bruins. Even without a ring, Driesell became one of the most beloved sports figures ever to toil inside the Beltway.

Good god, did Driesell make Maryland basketball matter. Throughout my teens, only the NFL team was above the Terps on the local sports totem pole. Teachers would bring TVs into classrooms for the first day of the ACC Tournament, so the kids who didn’t skip school to watch could keep up. I learned the maximum capacity of Cole Field House (14,500) from seeing that number as the attendance in so many box scores as a lad. I was over the moon when my dad got tickets to a game in 1975 and I got to see John Lucas and Brad Davis play together. (How’s this for a college backcourt: Lucas and Davis would go on to play 29 NBA seasons between them.)

Nobody out-recruited Lefty. His smile and that drawl surely helped him get mothers to entrust their kids to his care. But there were always rumors that Driesell didn’t leave it all up to charm. He landed Anthony “Jo Jo” Hunter, a prep legend at D.C.’s Mackin Catholic High School and maybe the biggest prize in the country in the recruiting class of 1976. Hunter told me some years ago that South Carolina’s legendary coach Frank McGuire met him in a D.C. restaurant and slid him a suitcase under the table with $75,000 in cash.

“But you went to Maryland,” I said.

“My mom got a house,” Hunter said.

Lefty's most famous recruit never played for him. Moses Malone came up from Petersburg, Va., after graduating high school, worked out in College Park, and declared in June 1974 he’d decided on Maryland. Every spurned suitor in the land accused Lefty of cheating to get him. But while NCAA investigators converged on the campus, Malone changed his mind and took a four-year, $565,000 contract with the ABA’s Utah Stars. He could buy his mom a house on his own.

So many exciting players came. By my count, 30 NBA draft picks played for Driesell at Maryland. The teams, alas, always seemed less than the sum of their parts. While just about every regular season was stupendous, the shortage of postseason successes meant Lefty never got the accolades of ACC peers like Dean Smith or Jim Valvano. And it clearly bothered him: He made a point of reminding interviewers that he wasn’t a failure. In 1981, when some local fans were calling for him to be replaced by local high school coaching fixture Morgan Wootten of DeMatha Catholic, Driesell told UPI reporter Don Cronin that he’d “smack anybody” who’d say to his face that he wasn’t good at his job.

“I may not throw out the Xs and Os like some coaches, “ he said, “but I can coach.” (The go-to impersonation of Driesell among me and my buddies was a very drawled, “Ah can coach!”).

His only ACC Tournament title came in 1984, with a team led by Len Bias, the only player from Driesell’s reign who outshined the coach. Bias's death by cocaine overdose in June 1986 brought the end of Lefty in College Park.

The basketball program had endured tragedies before. Two of Driesell’s players, Owen Brown and Chris Patton, died of heart attacks during pickup games within a couple months of each other in 1976. But Bias’s death, coming a couple days after the NBA champion Boston Celtics made him the second overall pick in the draft, was a bombshell way beyond the campus. His demise inspired Congress to pass odious mandatory sentencing statutes for cocaine crimes, also known as the “Len Bias Law.” Writer Dan Baum would later call Bias “the Archduke Ferdinand” of our government’s war on drugs.

There had to be a fall guy, and the media and the school went after Driesell in the months after Bias’s burial. Every few days another story would come out about Maryland players neither going to class nor progressing toward a degree, about a basketball program with no rules. No joke or level of likability was going to save the guy at the top. Driesell resigned in the fall, before the beginning of the 1986-1987 season.

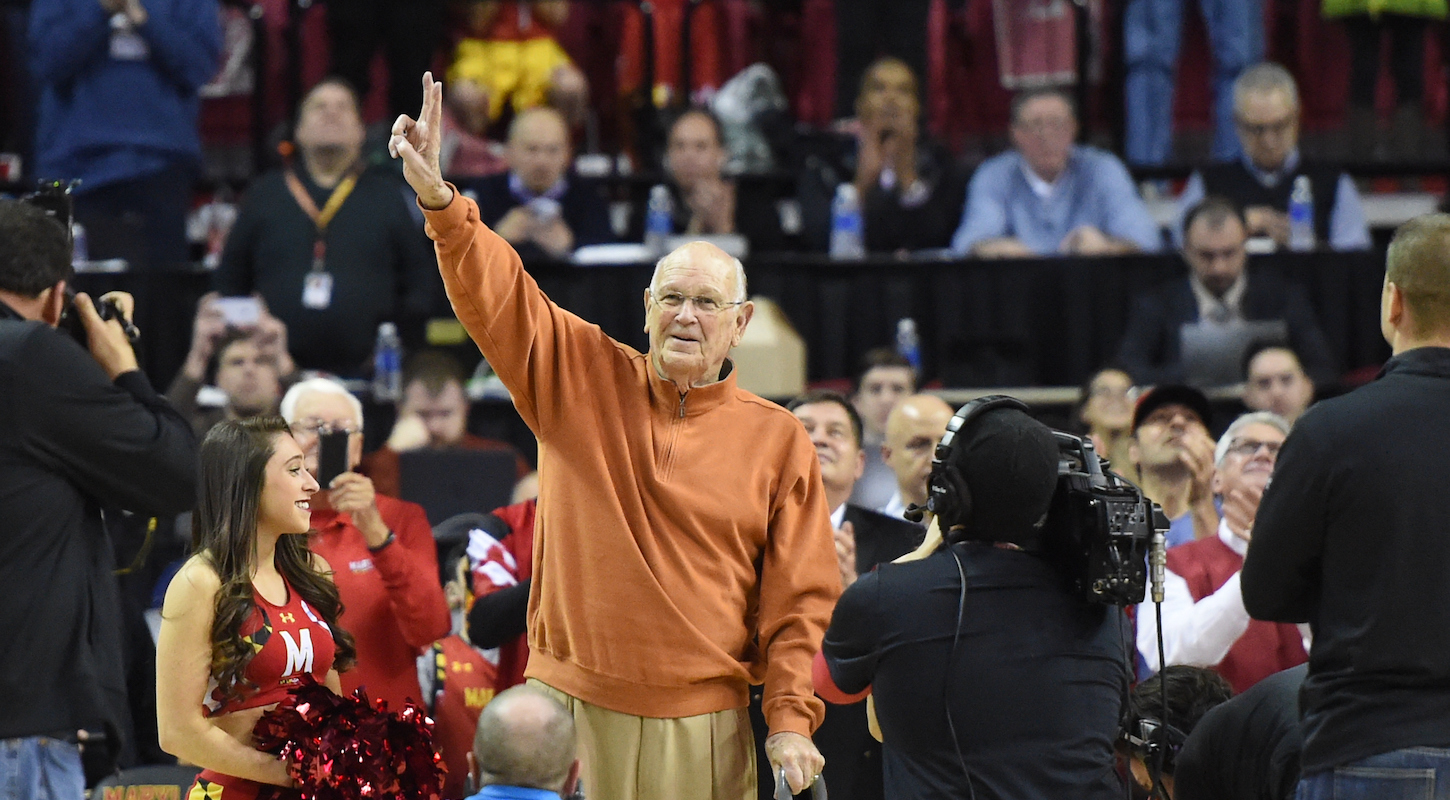

I saw Driesell at NFL games at RFK Stadium a few times after he was booted out of Maryland, sitting in the upper deck with the regular fans. After retiring from coaching in 2003, he left the D.C. area and moved back to the Hampton Roads area of Virginia, where he’d grown up and gotten that amazing accent. His connection to the Bias saga was surely what prevented Lefty from being inducted in the Basketball Hall of Fame until in 2018. He was gone but never forgotten by any local sports fan of my generation.

I was at a high-school game a few years ago and saw his son, Chuck Driesell, who played for Maryland under his dad and has been a coach for years at Maret School, a D.C. prep. I walked over to him and started thanking him for all the joy his father brought me as a kid. I started getting weepy right away and knew even in the moment that everything I was saying was coming out goofy, but I had to say it all and I meant every word.

RIP, Lefty.