Lusia Harris's college basketball coach, the soft-spoken Margaret Wade of Delta State University, wore a blazer on the sideline. Before the games, Wade would open up the blazer to show her players the lining, where she kept a button pinned inside that read "Give 'em hell." So Harris did.

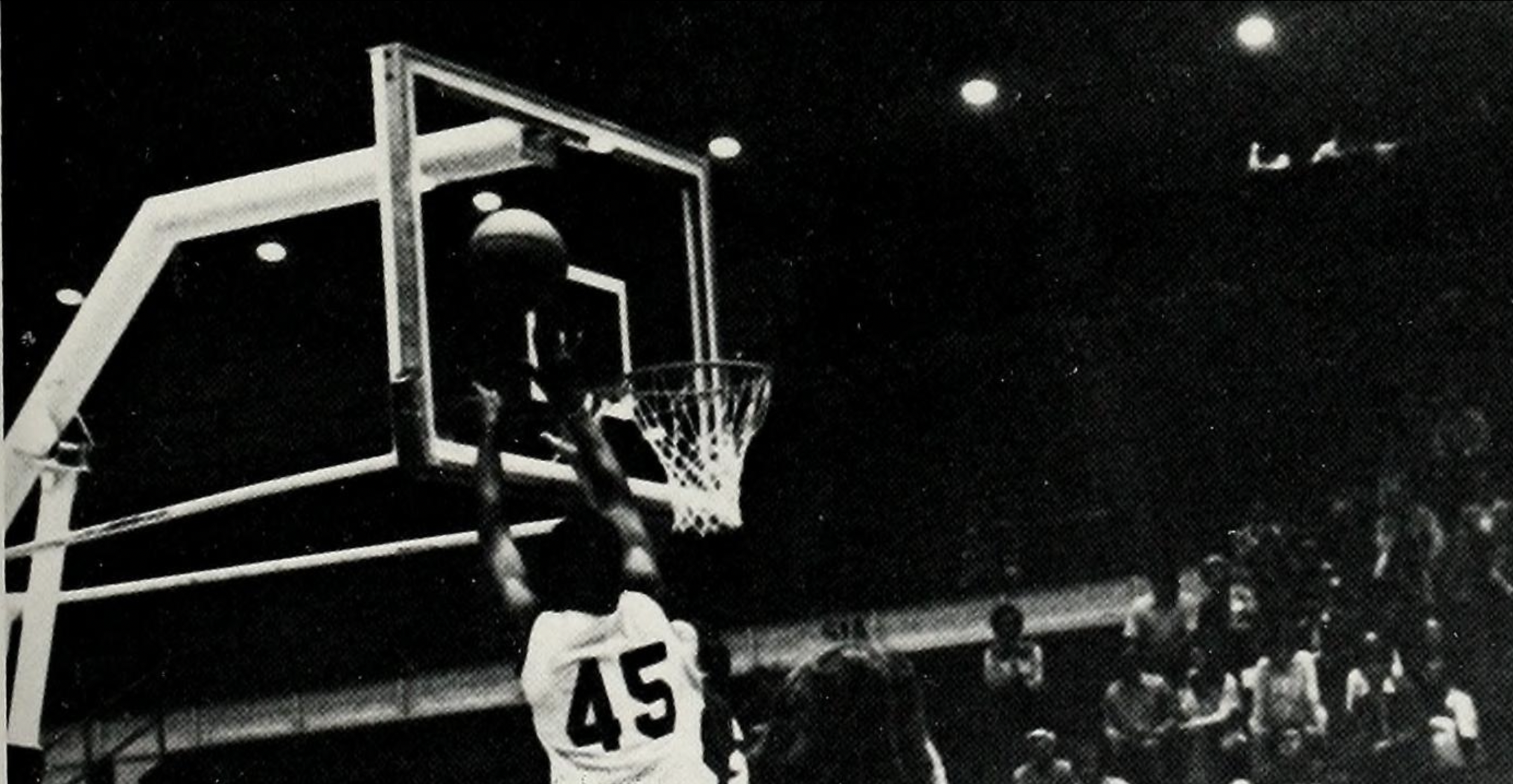

Her on-court dominance made the 6-foot-3, Mississippi-born "Lucy" Harris women's college basketball's first true star. In between winning three consecutive national championships at Delta State, the Hall of Fame center became the first woman to score in an Olympic basketball game, at the 1976 Montreal Games, and afterward, the first woman drafted to the NBA; the Jazz selected her in the seventh round. "I've had a lot of firsts to come my way, and I don't know whether I've just been at the right place at the right time or what," she told an interviewer in 1999. Such was the humility of a woman whose significance to the women's game and as a black woman on otherwise all-white teams she only began to acknowledge in recent years, as media interest in Harris's story grew. (The New York Times featured her in its "Almost Famous" documentary short series last summer.) Harris died, unexpectedly, Tuesday morning at the age of 66. Her quietly extraordinary life should serve as a reminder of all there is in women's basketball's history that needs preserving.

Not quite a year before she died, Harris gave an interview to the University of Kentucky's Women's Basketball Oral History Project. She discussed her childhood as the daughter of sharecroppers; her playing career from junior high through her brief stint as a professional player in the Women's Professional Basketball League in 1980; the distance her white teammates kept from her; the NBA draft she dismissed as a publicity stunt she wanted no real part in; her later frustrations coaching at a school unwilling to devote any resources to its women's program; her pride in her four children; and the landscape for women's basketball players as she saw it, one that's given rise to exciting activism, though fair pay remains a struggle.

The interviewer was Valerie Still, a great college post player herself in the early '80s at Kentucky, where she still holds the school records (men's and women's) for scoring and rebounding. I called Still Thursday evening. She was devastated by Harris's death—the two had stayed in touch since the interview, which Still described now as her "most cherished basketball moment"—but she said she was grieving something else, too. Generations of women's basketball players, many without scholarship offers, many without professional leagues to play in, had lived these marvelous, forgotten lives. Abruptly, their basketball careers had ended for lack of opportunity, often at the height of their games, and the stories were cut short, just like that. How many people, Still lamented, were learning about Lucy Harris now only because she had died?

If Harris resented the erasure that befell many great women's players, she never showed it. Her demeanor, sweet and quiet and quick to laugh, belied her intensity as a player. "She's the type of player that would be productive today," Still said. "If you put her in the game today, even without all the new technology and the new training, she would still kick ass. She'd be wearing them out. But if you put her through all this training and give her all these options and all these new technologies, man, there wouldn't be anybody to stop Lusia Harris."

Harris's teammates and coaches praised her skilled footwork inside. Her game looked effortless, even when she was being double- and triple-teamed. In fact, she said in the Times documentary that her shot just came naturally, without needing much refinement. All you really had to do with Lusia Harris on your team was to surround her with guards who knew their job. "The ball would zip around and then to her and no one could ever stop her," the women's basketball writer Mel Greenberg told me.

In Memoriam: Lusia Harris (1955-2022) pic.twitter.com/RgdwFioYBM

— WNBA (@WNBA) January 19, 2022

"I've always been an advocate for getting our history right," Still said. "And Lusia Harris is one of the reasons." The WNBA posted a video tribute to Harris on Wednesday—sweet in the sense that the WNBA represents possibilities denied to Harris; somewhat ironic if you know the league's reputation for being a neglectful keeper of its own history, let alone of all the women's basketball that preceded it. (That's not to say the important work of preservation isn't being done elsewhere. See the aforementioned Kentucky oral history project, journalist Bria Felicien's site The Black Sportswoman, and Kurtis Zimmerman's Across The Timeline.) I'd known of Harris and of the Delta State teams, but a revelation to me upon her death was how young she really was, how in a relatively short time she'd seen so much transformation, in the country she had once represented and in the sport that owed her a longer memory.