Long ago, after one of the two hometown decisions by Philadelphia judges that threw sand in the gears of his early career, Marvin Hagler, not yet Marvelous, got the word from Joe Frazier. Hagler was going to have trouble sliding up the greasy pole of his chosen sport because he had three things working against him.

“You’re black,” Frazier told him. “You’re a southpaw. And you’re good.”

Later in his career, when he had become Marvelous, and a world champion to boot, Hagler still had those days stuck in his craw. The lousy decisions—to Boogaloo Watts and an absurd draw with Vito Antuofermo—and the artificial barriers that nearly denied him not only the fat purses but a career at the top of his sport entirely, all stayed with him. The adversity he overcame, so much of it arbitrary and unfair and sadly typical of his chosen vocation, was the basis for the iron will he showed in the ring, as well as how resolutely he remained in retirement, avoiding the siren song that has proven irresistible to so many other fighters, including Frazier, and Muhammad Ali. He walked away after another dubious loss, a split decision against Sugar Ray Leonard in 1987 that no less an authority than the great Jerry Izenberg called, “an injustice even by boxing’s strange standards,” and this was the final bit of evidence that those early days were still with him.

Leonard represented all those rewards that had been denied to Hagler as the latter was coming up. He was the smiling face of a new generation of fighters in the lower divisions that would keep the sport wheezingly alive after the great heavyweights of the previous decade left—or were carried out—of the ring. The 1976 U.S. Olympic boxing team, which included Leonard and the Spinks brothers, was central to this development and Leonard was its unquestioned star. Hagler had given up on amateur boxing in 1973 because, as he put it, “You can’t eat trophies.” When Leonard was fighting his way onto cereal boxes, Hagler was making $50 fighting whatever tomato cans were willing to get into the ring with him, and fewer and fewer were willing to do so when they saw what awaited them there.

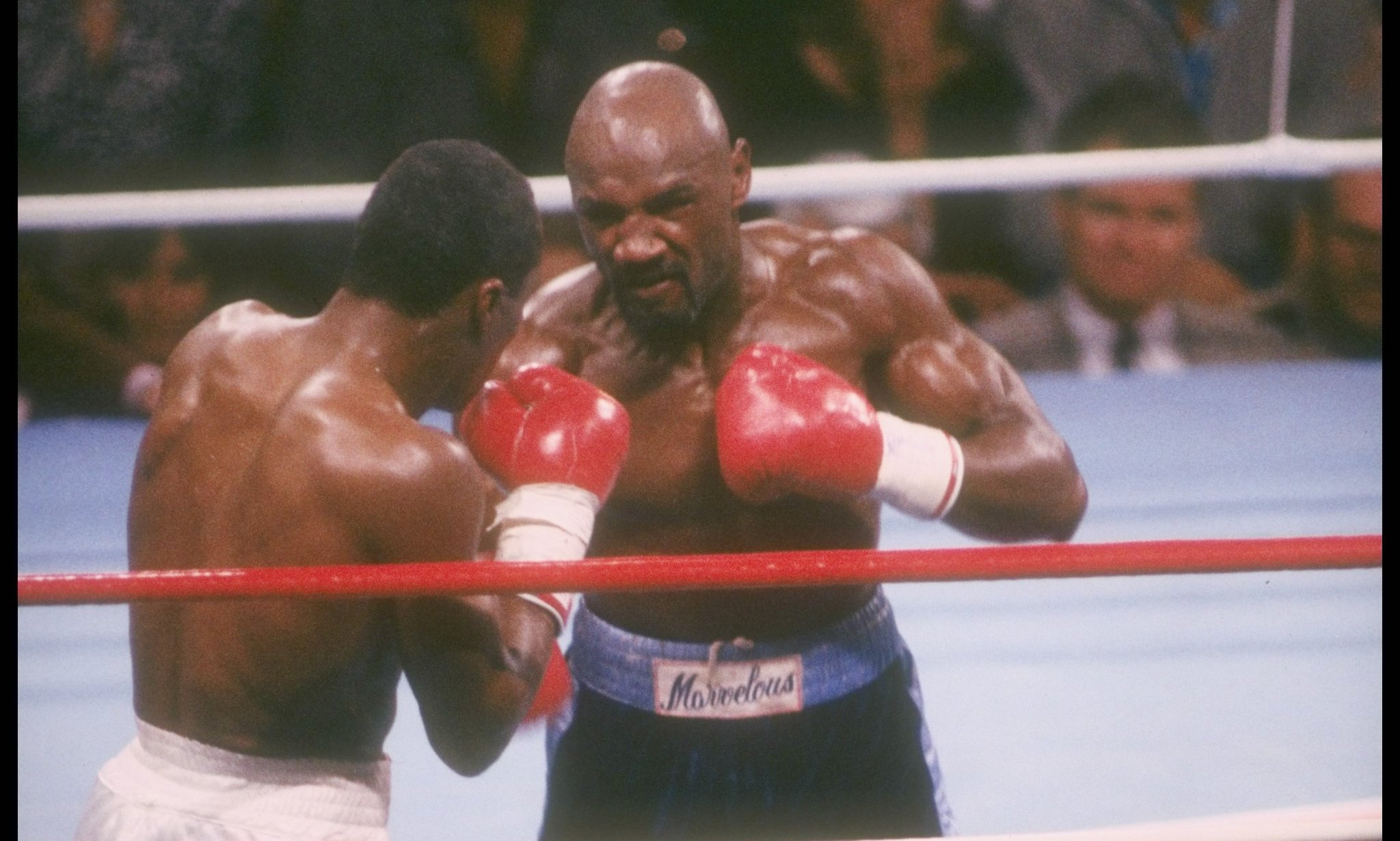

Hagler honed and refined his skills to a fine edge. He learned to go back and forth between southpaw and conventional right-handed styles, a tactic that he used to his own great advantage in the epic three rounds it took him to dispatch Thomas Hearns. But the one constant in his game was an indomitable stubbornness born out of an unquenchable will. He almost never went backward; only Frazier was so implacable on the attack. He threw punches, as the old boxing hands put it, with bad intent, and he expected his opponents to give him the respect of fighting him the same way.

So when Leonard came out dancing and fluttery in their bout, piling up points late in every round by staying out of the way and throwing punches that Hagler refused to respect, Hagler probably gave away two or three rounds just out of sheer contempt for the way Leonard was boxing. He lost because a judge named JoJo Guerra, apparently watching the fight from Neptune, gave him only two rounds.

In that moment, I believe, anyway, Hagler saw himself as having lost one more time to all those forces that had held him back all those years. Leonard was merely the personification of all of them in a way that Hearns, or John Mugabi, or even Roberto Duran never were. Rightly or wrongly, Hagler believed Leonard had been handed everything for which Hagler had had to fight. His entire career had been a battle for what rough justice could be found in his sport and, at the most lucrative end of the road, that reward had been denied him. He quit at 33, with a good bit of his money and almost all of his marbles. Later, when promoter Bob Arum came to New Hampshire to pitch a rematch with Leonard, Hagler’s response carried the sound of a great iron door, closing.

“Tell Ray,” Hagler said to Arum, “to get a life.”

My friend, the late George Kimball, wrote a terrific book called Four Kings about the days in which Leonard, Hagler, Hearns, and Roberto Duran ruled the middleweight division and fought epic bouts among themselves. In it, George describes how Hagler converted the usual trash-talking hype behind the fight against Hearns into the fuse that lit what became probably the greatest short boxing match of all time:

Hearns did his best to sell the fight on this whistle-stop tour, but seemingly every time he opened his mouth he managed to rankle Hagler with what Marvin perceived to be disrespect… "That tour did me good,” Hagler said once it was over. “I might’ve had some respect for Tommy before I spent all that time with him, but by the time we got done I came away hating his ass.”

Four Kings

It is now a cliché, this whole concept of "respect" and its lacking, that athletes use to psych themselves up. You will hear 6-5 favorites talking about how “nobody expected us to be here,” even though almost everybody who bet on the contest pretty obviously did expect it. In the encyclopedia of bullshit sports cliches, you will find this fact-averse bafflegab on one of the most well-thumbed pages. But every now and again, the truth comes out from behind the platitude. That was the presiding dynamic of Marvelous Marvin Hagler’s life and career. Nobody really did think he belonged. He was black and a southpaw and so very, very good. He remained staunchly loyal to the Petronelli brothers who had nurtured him and stood by him when the entire sport seemed to be conspiring against him, because a good portion of it was. He fought every fighter in front of him the same way, and he fought every fighter that was willing to step in front of him, even when there weren’t many of them. He bent a cruel sport to his iron will and, when it wouldn’t bend any further, he left it behind rather than let it devour him. Marvelous Marvin Hagler, dead this weekend at 66, finished the race and fought the good fight. He kept the faith.