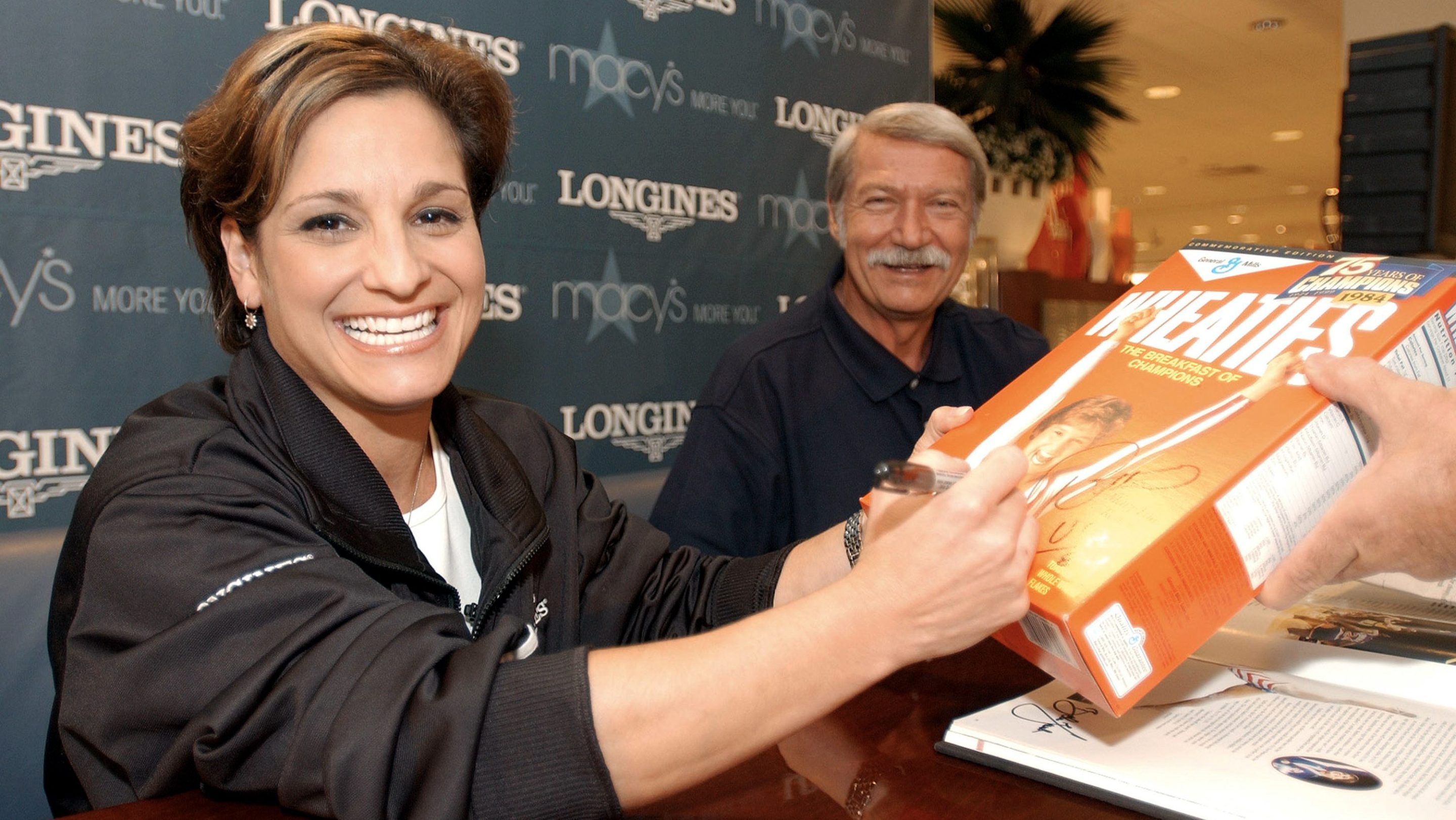

You can tell a person's age by how they remember Mary Lou Retton. For one generation, she is sparkly all-American girlhood personified, a pint-sized flash of brunette pixie hair with a megawatt smile and her arms thrust triumphantly in the air after she clinched the all-around gold medal in the 1984 Olympics—the first all-around gold ever for the United States in women's gymnastics. This also made her the first female athlete ever to grace the front of a Wheaties cereal box, the breakfast of champions. This happened back when social media didn't exist, and the cover of a cereal box really did define popular culture.

From there, Retton became a figurehead. She was the woman who threw out the first pitch at a baseball game, gave motivational speeches, and starred in a McDonald's commercial or an Energizer commercial or, years later, a menopause supplement commercial. All the recognizable duties bequeathed to or bestowed upon legendary former athletes at their various life stages.

But there is another facet to Retton, too. She is also the woman who used her position of authority to publicly defend USA Gymnastics when it became known that the institution had protected physically, verbally, and sexually abusive coaches for decades. As more women spoke out, starting in 2016, about sexual abuse by former USAG doctor Larry Nassar, and about the ways in which USAG leadership and coaches created the perfect culture of fear and retribution within the sport, which Nassar used to prey on athletes, Retton stood resolutely by USAG's side. In early 2017, when former Olympic gold medalist Dominique Moceanu called out USAG's leadership, and specifically then-CEO Steve Penny, for their role in the coverups, the organization responded by issuing a statement defending itself with Retton's name on it.

That same year, when legislation moved through Congress to try and address sexual abuse in sports, Retton went with Penny as the organization told politicians, per The New York Times, that "gymnastics was a happy, safe place." The SafeSport center, created in 2017 to address these issues, has been criticized by athletes for taking years to investigate cases, which makes its final resolutions ineffective, and for closing some cases without clear resolutions, and operating with too much opaqueness. It's clear from the Times' reporting that Retton was not there to argue that athletes deserved better than SafeSport, which they do, but that no outside program was needed at all.

Despite Retton's support, Penny eventually resigned and, when called to testify before Congress, repeatedly invoke his Fifth Amendment right to not incriminate himself. Retton, for her part, would again downplay concerns about abuse in gymnastics two years later during a 2019 appearance on Today. As Rachael Denhollander, the first woman to speak publicly about Nassar using her name, said at the time, "No. The monster put a spotlight on the decades-old cesspool. ... The refusal to admit the problem is why we have the problem."

Mary Lou Retton is not the first great athlete with politics that would make your stomach lurch. The soccer star Neymar has openly backed far-right former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro; future football Hall of Famer Aaron Rodgers peddles tired conspiracy theories during regular TV appearances. But few athletes cut as wide a figure in their sport here as Retton did in women's gymnastics. Even if Retton did get very lucky in 1984—the stacked Soviet Union team did not participate that year due to an Olympic boycott, meaning she did not compete against the entire field—she still was the first woman to win that coveted all-around gold. Her win really did send countless little girls into gyms all across the country; the Wheaties box really was that big of a deal.

Except now there's a third facet to Retton's all-American story, in one of the bleakest ways that term can be invoked. You will not be surprised to learn that it involves our healthcare system.

In October, one of Retton's four daughters, McKenna Kelley, herself a former LSU gymnast, posted on Instagram that her mother "has a very rare form of pneumonia and is fighting for her life."

"She is not able to breathe on her own," Kelley wrote. "She’s been in the ICU for over a week now." She added that her mother was uninsured. The family started collecting donations and, as word whipped around the internet, the numbers climbed. The goal was set at $50,000; according to the fundraising website, they raised more than $450,000.

Retton's family didn't say much beyond Instagram updates until recently, when Kelley spoke to USA Today; Retton and another daughter, Shayla Schrepfer, also did a sit-down interview with Today. Retton, using oxygen, said, "I just thought I was a washed-up old athlete."

Retton told Today that one day she felt a bit tired while getting a manicure with Schrepfer, and the next she was supposed to go to a football game with her daughters. Instead, she said she found herself on the bedroom floor, alone, unable to breathe. A neighbor went in to tell Retton about a door left open, found her on the floor, and got her to a local hospital. That hospital diagnosed her with pneumonia and sent her home a few days later, but Retton had to be hospitalized again after Schrepfer found her unresponsive. More tests didn't provide any answers about what was wrong; Retton's oxygen levels kept plummeting. At one point, Retton said, her own daughters didn't know if their mom would live.

Schrepfer said they started the online fundraiser because they didn't want their mom worrying about how to pay for her medical care after she recovered. Retton told Today that she couldn't afford health insurance after her divorce and losing work during the COVID-19 pandemic. She added that she is insured now.

The USA Today article, for which Retton declined to comment, goes into more detail about how one of our country's most famous Olympians ended up uninsured. Kelley told Christine Brennan that her mother couldn't afford health insurance because of all her pre-existing conditions. USA Today then asked Kelley about two quotes it had gotten on insurance plans for someone with Retton's medical history, the prices for which were $545 and $680 a month. Kelley added that her mother once had health insurance, but "because she was not able to work and give speeches for two years due to the pandemic, she gave up her insurance." Retton was about to get health insurance again, Kelley said, "and then she got sick."

Retton is now out of the hospital, and her bills have been paid. According to Retton and her daughters, doctors have few answers about what happened to her beyond that she contracted a rare form of pneumonia. The family said that any excess money donated for her care would go to charity but, per Brennan, neither Kelley nor Retton would say how much of that money was used, or what amount would go to the unnamed charity.

An ex-athlete—really any person—begging for help with their medical bills is a woefully common story in these United States. This country's healthcare system is ranked the worst in the world among the wealthiest nations; in lieu of a robust or even rudimentary social safety net, many Americans who get sick must tell their stories online and hope they go viral enough to get the cash they need to get well. Just as common is a person rolling the dice on their own health and skipping insurance to save the money, only to have their own body roll snake eyes. Every person gets sick, but the healthcare system in the richest country in the world seems built either to deny care or extract the maximum financial punishment for one of the most truly non-negotiable human experiences. Of course the end result is perverse—a competitive system in which virality and popularity and a suitably compelling tale of woe dictate who gets help, and whether they will escape getting sick without financial ruin.

We can now add a third facet to the all-American story of the quintessentially all-American girl. There is Mary Lou Retton, the gymnastics hero; there is also Mary Lou Retton, the celebrity supporting an organization against those trying to hold it accountable for its failures. And then there's the third act—Mary Lou Retton, a human in a body that gets sick in the ways that bodies do, who became just another person who had to drop their health insurance to save money, resulting in an online fundraiser to fill in the gap and unanswered questions about what happened with all that donated money.