Early last season, Matt Harvey pitched in Queens for the first time since the Mets traded him away in 2018. Mets fans, who had hitched some heavy hopes to Harvey back when he was arguably the most dominant pitcher in baseball in the early middle of the last decade, once the starting pitcher in the All-Star Game and either the future or a future for an organization that otherwise existed drearily outside of any legible concept of time or contention-cycle, gave him a standing ovation. Harvey set the Mets down in order in the first inning, then gave up four straight hits to start the second. He was charged with seven runs and lost, and he lost a lot after that. That was what Baltimore paid him $1 million to do; that was the price that the Orioles and the rest of Major League Baseball put on whatever was left in his arm.

Harvey made a team-high 28 starts for the Orioles in 2021. That he once seemed destined for more than being Reliably Available To The Worst Team In Baseball was academic by that point. Things had been trending this way for some time, and his rapid and turbulent progress down the shoulder of his career finally collapsed into the literal in Baltimore. Harvey was healthier than he had been in some time, and his underlying stats suggest that he was merely a prosaic kind of bad, but he was also objectively a pitcher with a 6.27 ERA on a 111-loss team. Everything that had come before that and after he left the Mets was equally forgettable, but all of it fits into the trajectory for a pitcher at the end—a low and uninspiring dead-cat bounce due to a change of scenery in Cincinnati, a make-good contract inevitably gone bad in Anaheim, seven brutal starts fired wanly down the memory hole in Kansas City during the pandemic-shortened season, and then, inexorably, that season of perfect entropy on a team seemingly purpose-built as an experiment in entropy-generation.

Baseball's myriad Guys, which Harvey has been one of for a lot longer than he ever was a Dude, tend to wind down in the same way. First little by little and then much more rapidly, curious or desperate teams take their shots at extruding whatever they can of what's left of their talent and then cut bait. Harvey's prolonged tour through the various rendering franchises at the bottom of the league's standings hadn't produced much in the way of potable juice despite the best efforts of everyone involved. The reputation as a churlish and self-invested jerk that Harvey developed during his brief, brilliant moment as a star surely did not make the prospect of giving his arm another squeeze much more appealing. This was true even before Harvey admitted, during the drug trial of former Angels communications staffer Eric Kay for his role in the 2019 overdose death of Tyler Skaggs, to buying and swapping pain medication during his time with the Angels, and to using cocaine during his time with the Mets. After his testimony, for which he received legal immunity, an anonymous MLB official reached out to ESPN’s T.J. Quinn to note that Harvey could face an immediate 60-day suspension should he land a big-league job.

There's nothing uplifting or ennobling to find here, at any level. Given the way that Harvey's drug use was covered during his time with the Mets, which was with alternately vengeful and prurient scorn, it's striking how normal and grim it all is. Harvey and several other Angels players talked about getting pain medication from Kay and, in the case of Harvey and Skaggs, from each other. They were in pain because being a professional athlete is hard on the body, and the pills helped with that; they were stressed out—in a 2019 text, Skaggs asked Harvey for a pill because he wanted to pitch "loosey-goosey"—and the pills helped with that, too. The ballplayers used drugs for more or less the same reasons that non-ballplayers do, and in more or less the same ways. As such, they faced the same kind of risk—not just of addiction or overdose, but of being marooned in the punitive state of exception that is still the norm where drug use and drug users are concerned.

Give or take a brief honeymoon period after arriving in New York, Harvey spent his entire time with the Mets in that space. "Harvey’s admission hardly came as a shock to those around the Mets," Mike Puma wrote in the New York Post last week. "There had been unsubstantiated rumors Harvey used cocaine, and his reputation as a hardcore partier only grew with each new team infraction, whether it was missing a workout before the 2015 NLDS or skipping a game two years later after he had stayed out late the previous night." Puma described a "line of demarcation" for Harvey after he had Tommy John surgery in 2013, and wrote that his struggles in re-entry—Harvey was still a mega-ace in 2015, and bravely if foolishly blew through a post-surgery innings limit during the team’s World Series run—had to do with realizing that he might never receive the nine-figure contract that had once seemed his destiny. (Harvey never got it; Baseball-Reference's estimate of his career earnings is well below what Jacob deGrom made last season.)

This may or may not have been true, but it was certainly how the Mets' sour and vengeful ownership saw it; it is how they treated basically every player they developed and every one that they ever paid. Accidentally or not, it is also absolutely congruent with how Harvey was covered by local media during his time with the Mets—as just another celebrity turd out for himself, hapless and vain and prone to nightclub canoodling and so inevitably and justifiably bound to be brought to earth by the punishing gravity of fame, or just by the type of media that sees that work as its mission. The Post ran stories on Harvey seeming intoxicated at a restaurant opening in Los Angeles where "nobody knew who Matt was" and also listicles on the models he dated. Whatever his habits did in terms of squandering his talent, no usable element of his celebrity was wasted.

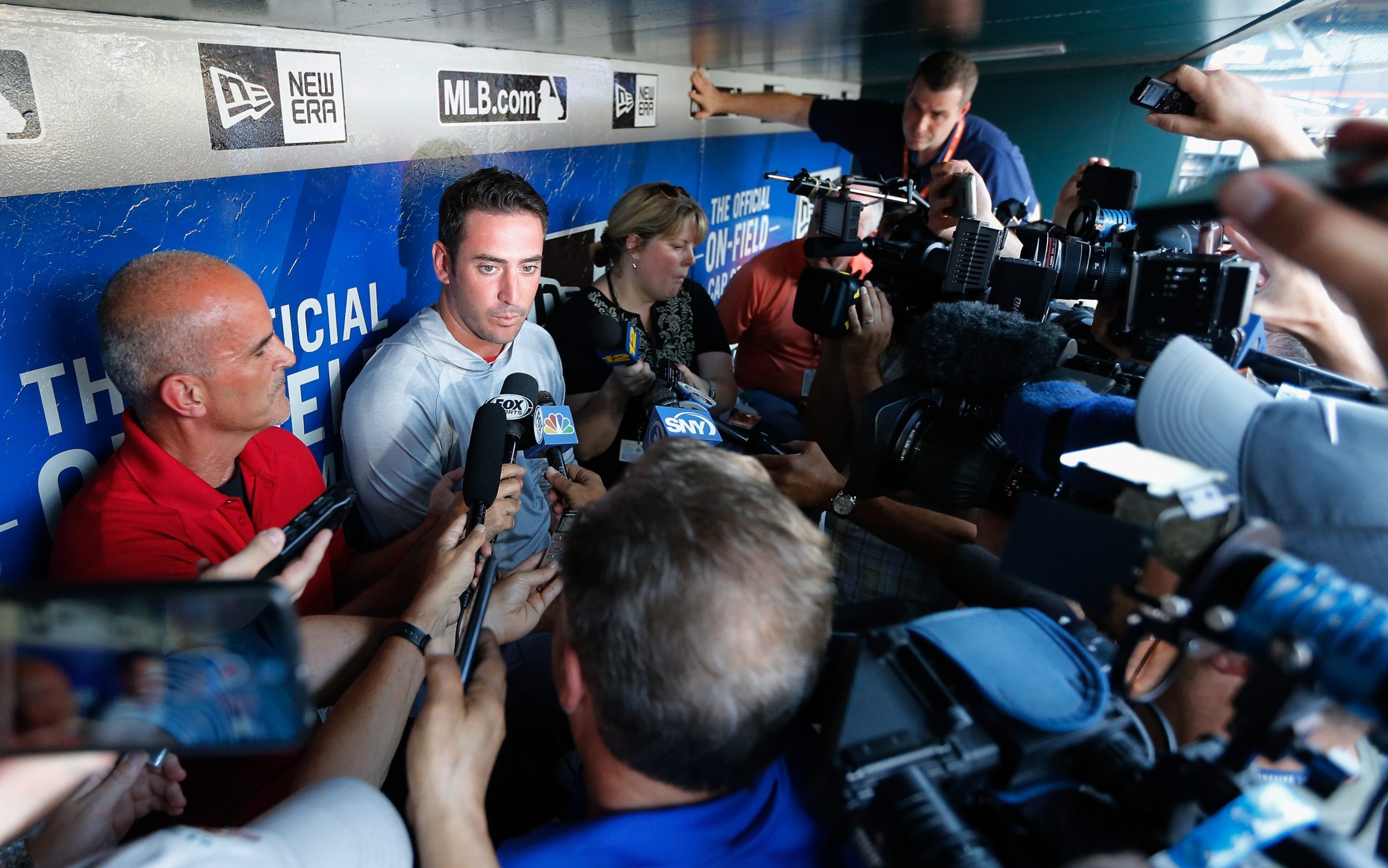

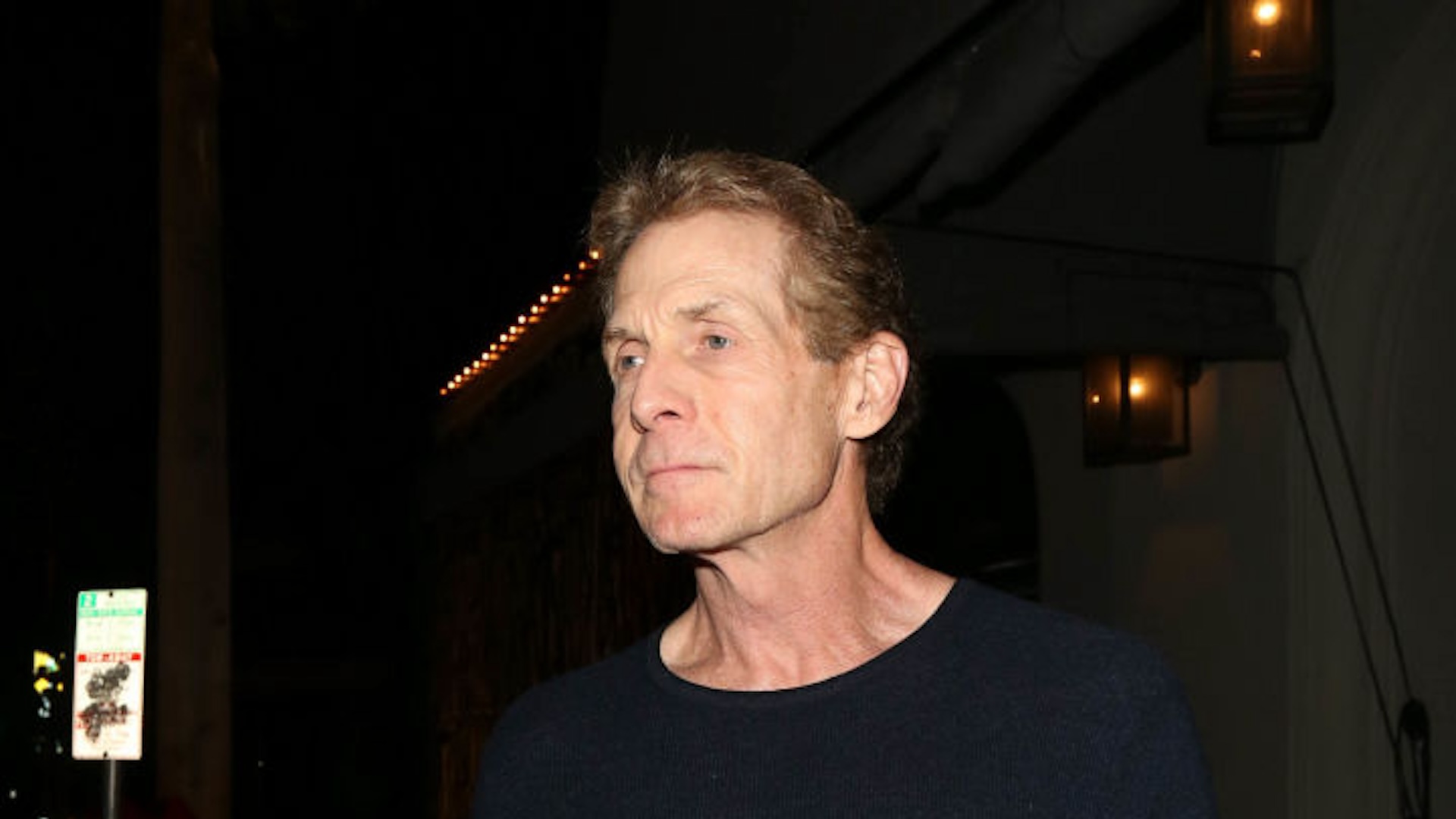

In the days after Harvey admitted to using cocaine while with the Mets, all those old grievances were aired again. Harvey's former manager Terry Collins, tanned to the color of a tamari almond, went on the team's cable channel to talk about it; when asked at trial if he had talked to the team about his cocaine habit, Harvey had said "no one really asked." On SNY and in the Post, Collins confirmed this. “Was there a time someone said, ‘Are you on something?’ without naming anything? That was probably brought up,” Collins told the Post's Larry Brooks. “But pretty much you addressed it as, ‘Look, you have got to clean up your off-the-field situation.’ That was it.”

Collins later mentioned that this was not quite it. "One time he talked about, ‘I should just kill myself,'" Collins said. "That’s kind of a common excuse. You try to deal with it the best you can. We certainly tried to get him help, get him some assistance." The Mets did this in the way those Mets did everything, which was grudgingly and grudgefully. In this case, it was a referral to the team's mental skills coach and a conversation with Dwight Gooden orchestrated by Jeff Wilpon, and with a minimum of effort and a maximum of damaging leaks to the local papers. As much as Harvey might have wanted that nine-figure contract, the Mets' former ownership wanted just as badly not to offer it; there was always someone willing to help them towards that goal.

The Post runs a lot of stories like this—it is something like their business model, and they still set the local standard for anti-human scuzz—but they are hardly alone in that work. Matt Harvey's career is, in a roundabout and ugly way, ending in the way that baseball careers end. It's ending because the game is hard and because bodies break, and because various personal failings and institutional failures invariably conspire to make it all that much harder and more punishing. Harvey made the mistakes that people make, by his own admission, and was in turn destroyed by bosses that wanted to destroy him out of strange jealousy and involuted institutional spite, and by a media that made him not just a target but a character in the broader sadistic story it exists to tell—about people who, for some imagined reason or combination of reasons, have stopped being human, and so are owed and deserve nothing.

Or not nothing. "Obviously there have been so many ups and downs here at this ballpark and with this organization that I didn't really know what to expect," Harvey said after his return to New York. "And what the fans gave me out there was pretty incredible. I was holding back tears. I'm not going to lie about that." Things might have been different for Matt Harvey, in a bunch of ways, but he got what he got—some appreciation too late, another loss among many, but finally just the extractive embrace that squeezes and squeezes, for its own ends, until there is nothing left and it is time to say goodbye.