Michael Zagaris started his hustle early. When he was a high school student in San Jose in the early 1960s, he was so taken by the athletes and musicians he admired that he wanted—craved, really—to insert himself into their lives. So he purchased colored paper from an art supply store and painstakingly handcrafted his own photography credentials. Armed with his dad’s London Fog overcoat and Ansco camera, Zagaris swaggered onto the field at San Francisco’s Kezar Stadium, where the 49ers played their home games, and started shooting NFL luminaries, everyone from Jim Brown to Vince Lombardi.

After Zagaris earned a football scholarship to George Washington University, he kept up the hustle. He informed the PR staffs of the Colts and the Redskins that he was doing research for a grand coffee-table book he called Sunday Gladiators—no such book existed—and scammed his way onto their fields in Baltimore and D.C.

In the summer of 1964, after he worked the Democratic Convention in Atlantic City, Zagaris and his younger brother Bruce were in New York to watch the Yankees and Mel Stottlemyre face the Orioles. When they saw that The Beatles were playing Forest Hills Stadium the next night, “We’re like, ‘FUCK!’” Zagaris recalled. “My brother goes, we won’t be able to get tickets for that.”

Zagaris picked up the phone in their room at the Taft Hotel and called down to the front desk. Easing into a Boston accent, he said, “Hello, this is Mr. Zagaris from Senator Kennedy’s office. We’re trying to get a couple of tickets to The Beatles concert tomorrow. Do you think you can help us out?”

Fifteen minutes later, there was a knock on the door. A concierge in liveried regalia and white gloves held out a silver tray, upon which were two tickets, second row.

“When the Beatles hit the stage, the screaming was so loud, we could barely hear them from the second row,” Zagaris said. “My brother yelled out, ‘Beach Boys Rule!’ and some girl slapped his face so hard you could see the handprint.”

Zagaris cackles with delight at the memory, and it’s impossible not to join in. We’re sitting in the living room of the San Francisco apartment he shares with his wife, model Kristin Sundbom, while The Old Man and the Sea on TCM plays silently on a large flat-screen TV. Ostensibly, we’re discussing his forthcoming book, entitled Field of Play: 60 Years of NFL Photography (published by Petaluma-based Cameron Books). It’s an exhilarating romp through his 60-year career shooting the NFL, starting from the amateur shots he took during high school to his job as team photographer for the 49ers, a post he’s held since 1973, not to mention the 40-odd Super Bowls he’s covered.

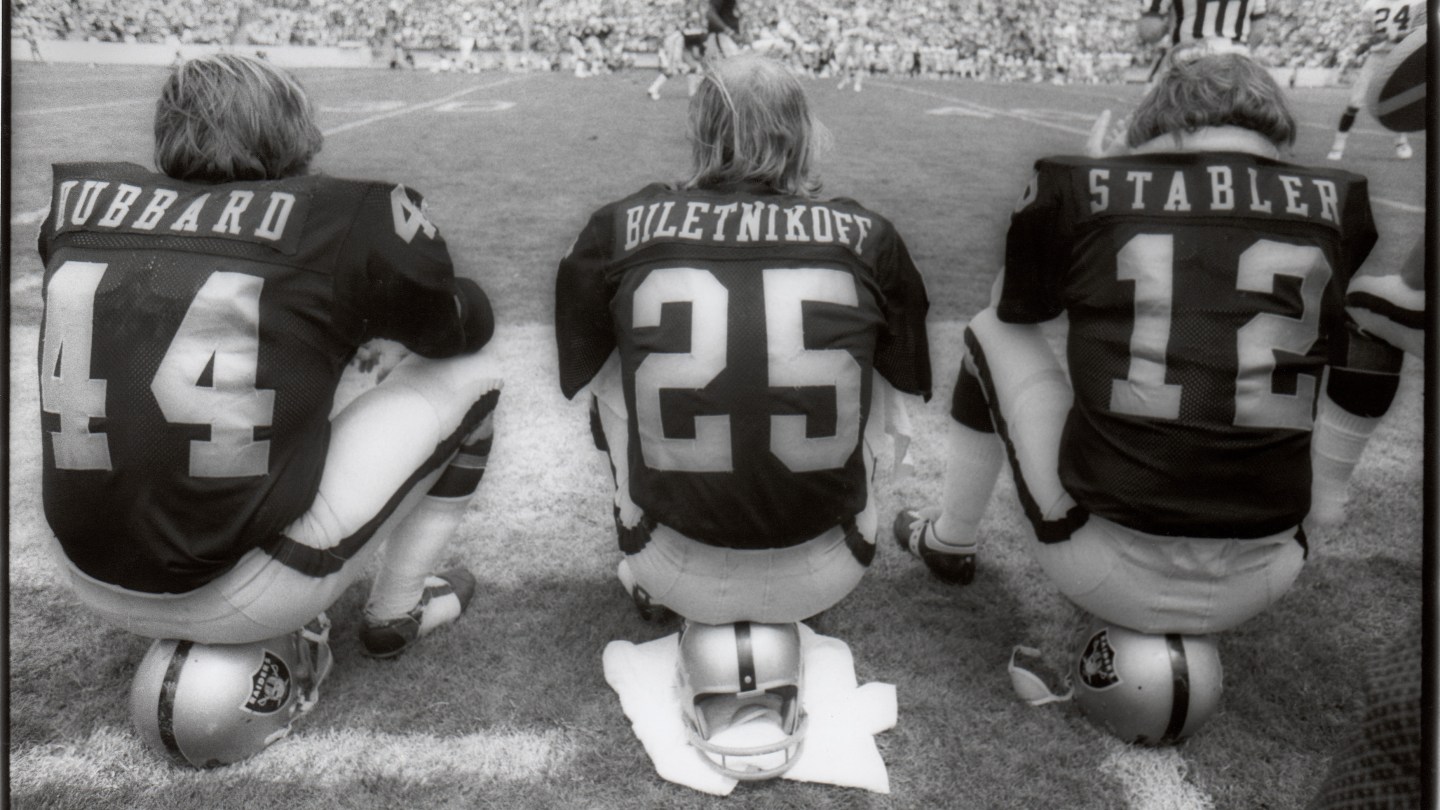

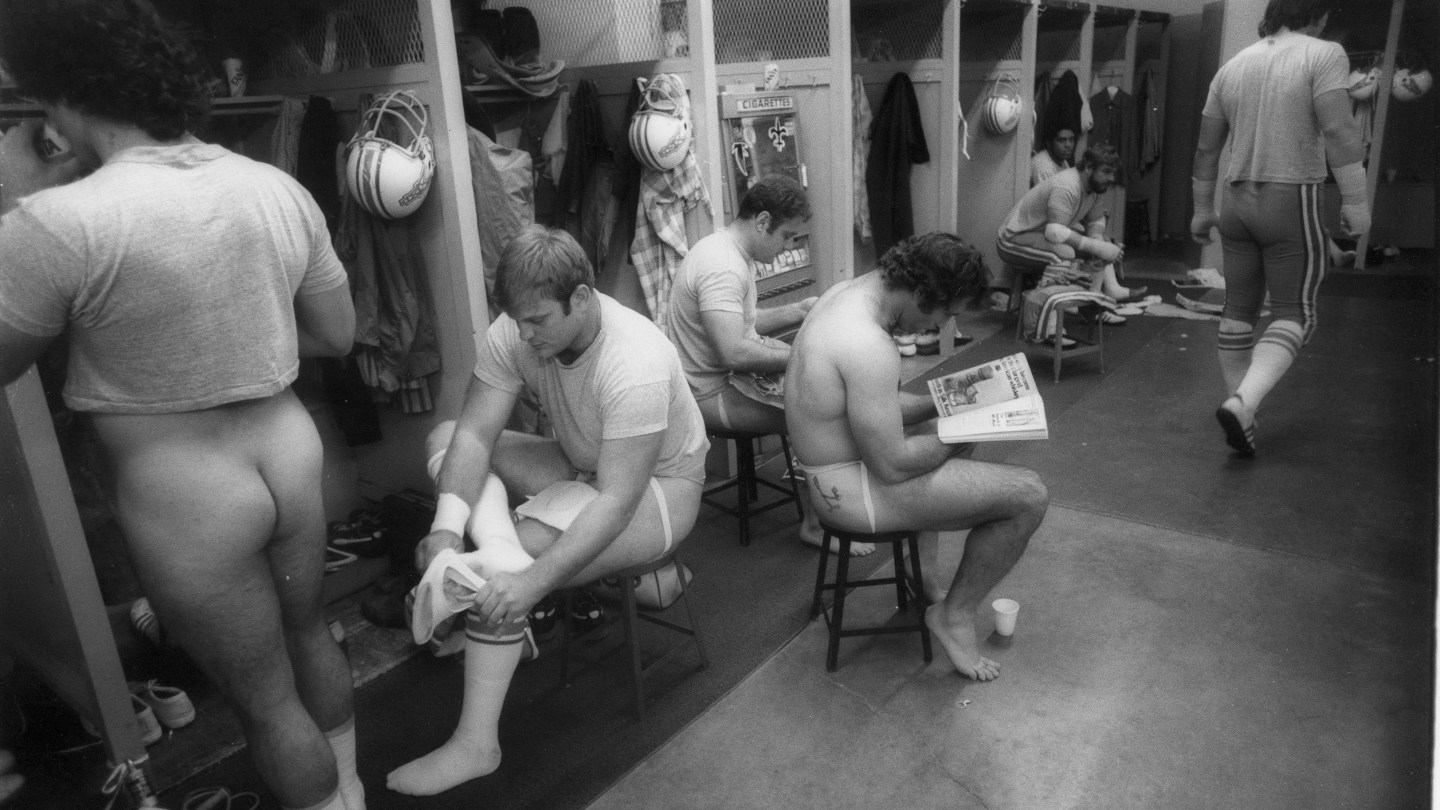

The book documents Zagaris’s uniquely idiosyncratic vision of the sport, and especially that era before the NFL became commercialized and commodified beyond recognition: when stadiums had nicknames like The Big Sombrero instead of corporate names, and the players had to navigate infield-dirt sections of the gridiron; when Charlie Krueger’s helmet resembled what Air Raid wardens wore during the London Blitz and Fred Biletnikoff slathered on Stickum like Jackson Pollock. In this, the book is a paean to the pioneers whose black-and-white pictures transfixed and inspired Zagaris in the 1950s and early 1960s: photojournalists Robert Riger, Vern Biever, Herb Weitman, Frank Rippon, and Fred Roe. Their imagery set the template for how NFL Films would present pro football in its sweaty, bloody, mud-encrusted glory—it’s the gritty vibe seen in The Hustler and On the Waterfront, two films that Zagaris references whenever he discusses shooting inside a locker room.

But you can’t speak with Zagaris, still spry at age 77, without talking about his cosmic life outside of football. An inveterate raconteur who delights in epic tangents and profanity-infused rants, Zagaris—pretty much everyone calls him Z or Z-Man—has served as the Oakland A’s team photographer since 1981 (or, right after Charlie Finley sold the ballclub). He’s also amassed a remarkable cache of photographs during the years he was embedded in the Bay Area music scene, shot at places that exist only in musty memory: the Winterland, the Avalon Ballroom, the Boarding House, the original Fillmore.

“To me, I’m not a sports photographer,” Z said. “I’m not a music photographer. I’m not a fashion photographer. I’m a photojournalist. I want to live the experience I’m shooting, and my camera is merely a mirror that I’m holding up to document this and then share with people."

Born in Chicago, Zagaris’s family moved to California when he was two. He was raised a Catholic and grew up in the Central Valley towns of Modesto, Hanford, Stockton, and Redding, what he describes as “redneck country.” “You might as well be in Mississippi,” he said.

Z played football and baseball at Bellarmine Prep, a Jesuit school, before entering George Washington. Photographing Sunday’s heroes was mere pastime; his goal was to play college ball, go to law school, and pursue a political career. All went according to plan until the early morning hours of June 5, 1968.

He was working for Bobby Kennedy’s presidential campaign. A suit-and-tie-wearing student at Santa Clara University’s School of Law, Z was standing inside a ballroom at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, celebrating Kennedy’s triumph in the California primary, a victory that he and other supporters believed would propel Kennedy to the Democratic Party nomination over Vice President Hubert Humphrey.

After Kennedy’s victory speech, Z followed the crowd exiting the ballroom through the hotel kitchen when he suddenly heard several loud bangs. “It sounded like somebody let out a string of firecrackers,” he said, “because I didn’t equate it with gunshots. I took a few steps into the kitchen, slipped, and almost fell. I thought it was oil, but it was blood from Paul Schrade, the union man [one of five other people shot by Sirhan Sirhan].”

Inside the cramped space was “pandemonium,” Z said. “Rosey [Grier, NFL star and RFK bodyguard] had someone against the wall. People were yelling, ‘Break his hand, break his hand!’”

Z wasn’t carrying a camera. He remembers seeing Life magazine photographer Bill Eppridge trail Kennedy into the kitchen before capturing the moment when busboy Juan Romero cradled a dying Kennedy while awaiting the arrival of the paramedics. (L.A. Times photographer Boris Yaro captured a similar photo.)

“I didn’t see Bill again until decades later,” said Z, referring to Eppridge’s long stint at Sports Illustrated. “He went through it. That really fucked him up.”

So, too, did Z go through it. After he flew back to San Francisco, he sat for a contracts exam at Santa Clara. He filled blue book after blue book with screeds of discontent about America and its future. He dropped out of law school and dropped acid for the first time, taking in the 360-degree view of the universe from atop Mount Tamalpais, just across the Golden Gate Bridge in Marin County.

“After the assassination, I was like, fuck America,” he said. “My first acid trip was transformational. I learned more than in college, law school, working for the Kennedys.”

Z didn’t so much retreat from mainstream politics and religion as recalibrate himself. “The Vietnam protests, the Civil Rights protests, the sexual revolution, LSD and psychedelic drugs: I thought that we—our generation—were changing things as part of a renaissance.”

He tried to join the Black Panthers, but was rebuffed at gunpoint at their headquarters in Oakland. He burned his draft card in an anti-war demonstration on the steps of San Francisco’s City Hall at the instigation of Muhammad Ali. “He said, ‘You got a draft card to burn, brother?’” Z recounted. “I said, ‘Yeah.’ I took it out, and he gives me some matches. So now I have to burn it. I still have a little bit of the draft card left.”

His search for self and purpose, a lifelong quest that continues apace, led him to the epicenter of the counterculture: Haight-Ashbury, home of be-ins, acid tests, and tie-dye. One of his landlords was Michael McClure, the Beat poet and playwright. Nearby lived members of the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and Z’s favorite, John Cipollina and Quicksilver Messenger Service.

He taught junior high school in East Palo Alto. His father kept asking him what he was going to do with his life. “I was like, ‘I don’t know, but I’ll know when I find it.”

Z concocted a book idea about how American blues/roots music influenced the British rockers, and set about interviewing the likes of Eric Clapton, Peter Frampton, and members of the Stones. Z says that it was Clapton who convinced him to eschew writing and concentrate on photography.

He never took a formal class. He learned by doing: how to use available lighting and how to print in a darkroom. He pored over Italian fashion magazines and studied the work of Sarah Moon, Deborah Turbeville, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Robert Capa. He experimented with different lenses and color and black and white film, made mistakes and figured out how to correct them. He gleaned knowledge and attitude from masters in situ, including Jim Marshall and Baron Wolman, and befriended benefactors who opened doors for him, like uber-promoter Bill Graham.

“I constantly asked questions and I kind of evolved,” he said. “I didn't much have a plan, and I know that seems crazy. My whole life has kind of been like that, where I walk through life with my eyes open, letting everything just come through me, and the things that really resonate I’ll explore more.”

He discovered that, with a Nikon in his hands and a (real) media credential, he had a backstage pass to hedonism. He shot the psychedelic scene, the punk scene, and the underground scene. He shot blues vocalists and guitar gods, album covers and magazine covers. After meeting poet Jim Carroll at their coke dealer’s flat, Z shot Carroll and his band (“People Who Died”) in a graffiti-ed alley in North Beach. From that shoot came the portrait that graced the trade-edition cover of Carroll’s landmark The Basketball Diaries, later made into a movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio.

“I thought, I can’t be in the band, but if I’m doing this, it’s almost like being in the band,” he said. “And when you’re going from the hotel to backstage to on-stage—it’s you, the band, the roadie, the manager, maybe a girl or two, and the dope dealer—you’re part of it. Lines are laid out, sniff sniff, smoke a joint, now we’re going down this long hallway, someone’s got a flashlight to guide you, you go up the stairs, you see the gear, the amps are humming – whee, whee – and then the music starts … To me, that’s it. Fuck the money. This is why we’re doing it. Pure adrenaline.”

For Zagaris, it was a natural progression to pursue shooting his other lifelong passion, sports, and he landed paying gigs with the 49ers and A’s. “It was easy with football and baseball because I played in high school and college,” he said. “One of the reasons I segued back into sports in the middle of [shooting] music was, I missed the scene. I missed hanging out with guys in the locker room. It’s like never having to grow up. I mean, where else can you go from 8:00 in the morning till midnight and just talk sports and give each other shit and do things that you could never do in a real job?”

During the pandemic, Z’s crowded schedule slowed enough that he had sufficient time to curate his collection of thousands upon thousands of football photographs, assisted by Steve Fine, the longtime Director of Photography at Sports Illustrated, and baseball photographer extraordinaire Brad Mangin. (The book also includes journalist-author Steve Cassady’s ribald essays about running with Z as well as reminiscences from Fred Biletnikoff, Joe Montana, Ronnie Lott, and Dr. Harry Edwards.)

“I started going through things I hadn’t seen in 20 or 30 years, especially the early stuff,” he said. “That’s the great thing about pictures. Each picture triggers not only a memory, but a flood of memories—smells, who I was dating back then. Everything you’ve ever done, witnessed, experienced—it’s there. You never forget about it.”

The book shows his evolution as a photographer as he switched from Nikon to Canon, from black-and-white to color, from film to digital, from manual focus to autofocus. “I’ve never been an equipment guy,” he said. “At first I was like, ‘Fuck digital. I’m never going digital.’ Then it was inevitable. And there’s some things with digital that you could never do with film, and vice versa.”

A sizable chunk of Field of Play chronicles the glory years of the Raiders, when Kenny Stabler and Biletnikoff ruled Oakland, and Al Davis and John Madden haunted Pete Rozelle’s staid NFL. “The Raiders were not only a good team, they were colorful,” Z said. “They were like the Gashouse Gang. Al Davis was a trip, and the players partied hard. The shit that I saw in rock and roll, it was the same—not quite to the excess or degree, but almost.”

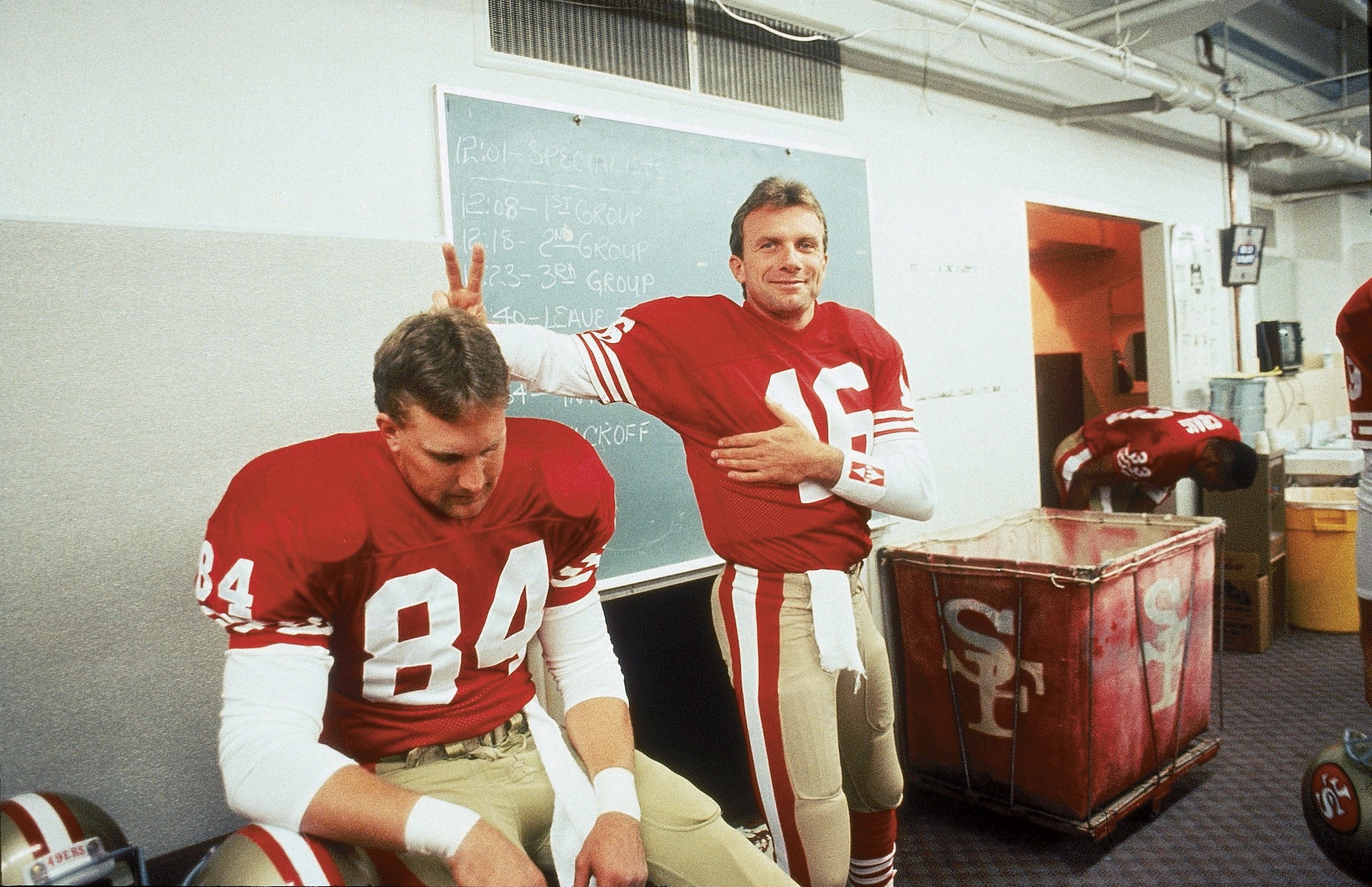

His coverage of the Bill Walsh era of the 49ers is equally dynamic. Before Walsh was named head coach in 1979, the franchise was a mess. The Niners had finished 2-14 the previous season and gone through five coaches in four years. They hadn’t made the playoffs since 1972 and had never come close to reaching a Super Bowl.

Z approached Walsh with a novel suggestion: to capture the 49ers from an insider’s perspective. “I talked to Bill maybe three weeks after he became head coach,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Coach, I think you’re going to do great things here. What I want to do is cover this team as a historian, but I want total access. I want to be able to go on the buses, and I want to shoot pre-game. I want this to be a player’s and a coach’s view of the game. A history not just for the team, but for the league.’”

This was Walsh’s first head coaching job in the NFL, and it would’ve been easy for him to say no. But he didn’t, perhaps because he had Bay Area roots and understood Z’s perspective. Or, perhaps he was taking a cue from Vince Lombardi, a media-savvy coach who welcomed writers like W.C. Heinz and Dick Schaap into the Packer fold, along with photographer Vern Biever (and, later, Vern’s son John), all of whom helped mythologize Lombardi and the Green Bay dynasty.

Whatever the reasoning, Z witnessed one of the most remarkable turnarounds in NFL history, as Walsh revolutionized the pro passing attack, rode Montana’s arm to three Super Bowl wins, and established a distinguished coaching tree (Pete Carroll and Mike Holmgren, to name a couple).

Z gained the players’ trust by adopting their daily habits, something he continues to do today. He changes into work clothes at his own locker, flies with them to away games, rides the team bus to the stadium, and laces up his cleats when he takes the field. With familiarity comes unfettered entrée, and his vérité photos often expose the game’s brutality that the public seldom sees. There’s Montana, concussed, staring mindlessly on the sideline as teammates gather to support him. Here are multiple players getting painkiller injections before and during games.

Describing football as “borderline masochism,” Z debated whether to publish these photos. “There’s a possibility that [the NFL] will go, ‘Hey, you know what, you’re done,’” he said, because “they want to control the message, the narrative, and that’s why this will piss them off. My thing would be, ‘Fine. I’ve had a great time. There’s no bitterness.’”

On the journey from Kezar to Candlestick to Levi’s were sublime dramatics, including “The Catch,” the Montana-to-Dwight-Clark TD connection that buried the Dallas Cowboys and sent the 49ers to their first Super Bowl. Z’s picture of that seminal moment appears in the book, although he admits that his angle wasn’t optimal.

“Everyone remembers Walter’s shot, as they should, because that was a great fucking shot,” Z said, referencing his friend Walter Iooss’s photograph that was published on the cover of Sports Illustrated. “I was on the other side of the field because I thought it was gonna be a sweep. The play before, Joe overthrew Freddie Solomon in the end zone. I was in the right spot for that one. The ball almost hit me.

“Sometimes you have to be lucky,” he continued. “We talk about it all the time: how did you know that was going to happen? You don’t. And, sometimes when you do: I may know a fastball’s coming, but that doesn’t mean I’m gonna square it up and hit it.”

Z took the book’s most compelling photo at San Diego’s Qualcomm Stadium before the Niners’ final pre-season game of the 2016, when Colin Kaepernick kneeled for the first time during the playing of the National Anthem, in protest over social injustice and police murders of black people. The picture features Kaepernick on bended knee, bracketed by teammate Eric Reid (who was injured and not in uniform) and Nate Boyer, the former long-snapper and Green Beret who had persuaded Kaepernick to take a knee instead of sitting on the bench during the anthem.

During the regular season, when the 49ers played at Buffalo just before the 2016 election, Z followed Kaepernick out of the tunnel. “People are yelling shit, throwing shit, someone said ‘nigger,’” Z said. “I’m thinking, this is what it must’ve been like for Jackie [Robinson] in ‘47.

“The myth that we were sold was never true, and our people aren’t extraordinary,” Z continued. “People are the same everywhere. The sad thing to me is our species: We’ve never gotten it. We’re still doing the same dumb shit. We’ve never learned.”

Kaepernick was “pretty much a loner” who alienated some players “because he kept his headphones on and wouldn’t talk to guys on the team,” Z said. That doesn’t diminish his admiration of Kaepernick for taking a stand as “the modern-day version of Tommie Smith and John Carlos” at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. (Time magazine later used another of Zagaris’s photos of a kneeling Kaepernick on its cover.)

“Kaepernick had an awakening,” Z said. “He articulated many, many times at great length what he was doing and why. What’s ironic to me is, if people are saying something you don’t want to hear, then you don’t hear it and you make up your own shit.”

Zagaris doesn’t plan to slow his hustle anytime soon. Getty Images handles the distribution of his sports pictures, and a feature-length documentary about him is nearing completion. He published a ravishing book of his music pictures in 2016, entitled Total Excess (Reel Art Press), and sells signed prints. He plans to compile his baseball pictures into a coffee-table book, and keeps threatening to publish a book of photos of S.F.’s underground scene from the early 1970s.

“It wouldn’t sell much,” he said. “It might be the most artistic work I’ve done. I know that, for people who follow my work, it would be a bridge too far for many of them.”

He still lives in the Haight. He’s rented in the area for 50 years now, since back when he could’ve purchased an entire Victorian for $25K. Today, busloads of tourists flock to pay homage to the husk of an epoch, amid the omnipresent scent of Humboldt-grade ganja.

With his wife Kristin, Z occupies a three-bedroom walk-up that’s chock-a-block with shelves of oversized photography books and LPs. One room is crammed with bobbleheads, old football cards, posters, and a piece of that charred draft card; boxes upon boxes of negatives, prints, contact sheets, loupes, press credentials, and supplies fill another room. A storage unit houses the bulk of his archive.

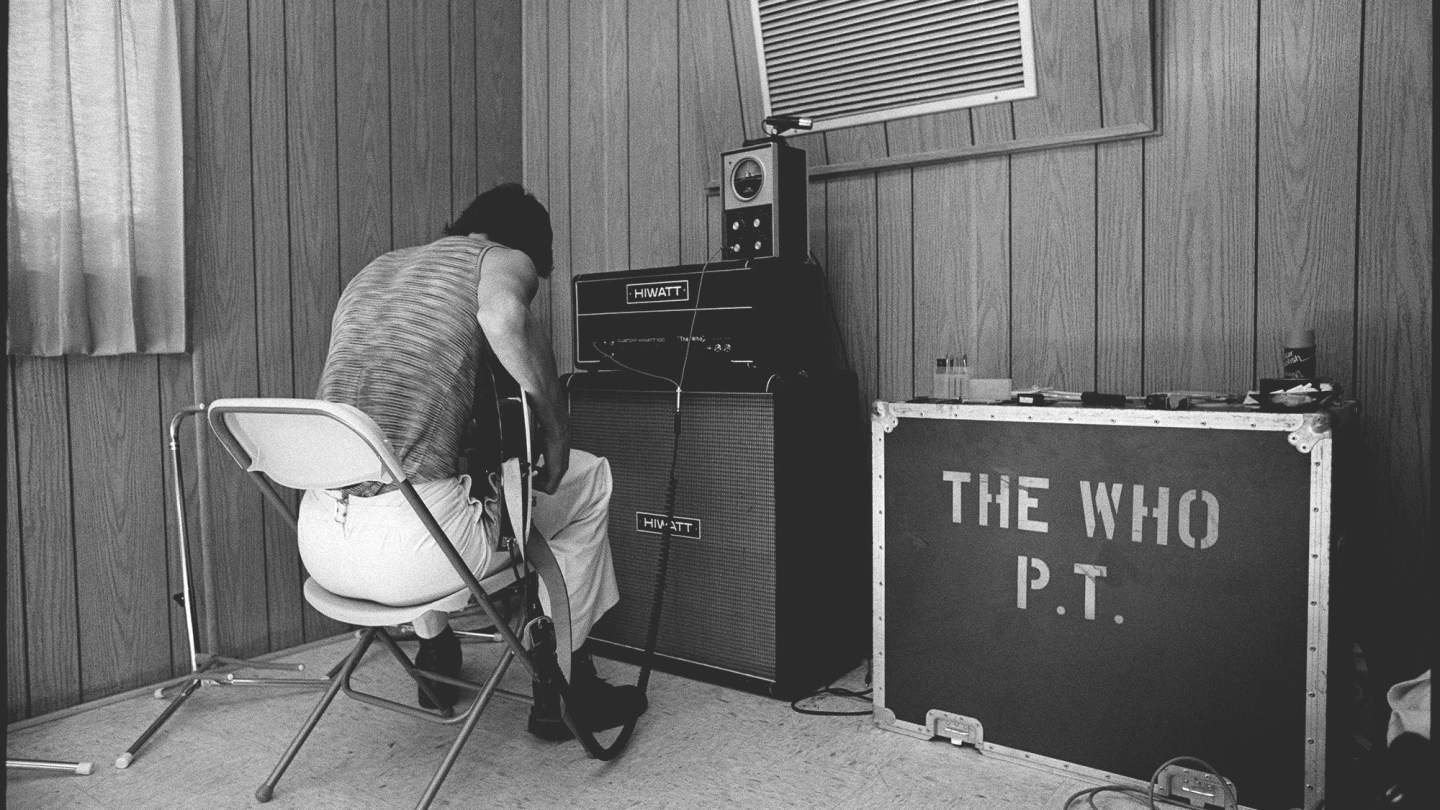

Vintage images from his years shooting music line the walls: Dylan, Nico, The Who, The Dead, The Sex Pistols, Lou Reed, Jimmy Page, Jim Morrison, Etta James, Patti Smith, Blondie.

Z stops in front of a black-and-white photo of Pete Townshend throwing his guitar in the air at The Winterland, hundreds of sweaty fans providing an exultant backdrop. Just before the band went onstage, Z recalled, Keith Moon proffered a plastic baggy.

“What’s that, beef jerky?” Z asked him.

“No, mate,” replied Moon according to Z, mimicking the drummer with an accent out of Spinal Tap. “That’s magic shroomies.”

Z tripped so hard that he had to retreat to the balcony to regain a semblance of sanity. Hence, he was in perfect position to capture Townshend’s guitar-toss in what turned out to be The Who’s last U.S. tour with their original lineup.

The kicker: “As soon as Moon stood up after the show,” Z said with delighted cackle, “he fell face-first into his drum set and had to be carried off the stage.”

A framed photo in the bathroom shows Rick James appearing to snort an actual boulder. Z recalls that, when he went to the Record Plant in Sausalito to shoot James for Rolling Stone, he found the singer in the arms of actress Linda Blair, with a humongous pile of coke sitting on a nearby table.

“I wanted to take him to the Golden Gate Bridge and shoot him underneath Fort Point,” Z started, and another you-had-to-be-there yarn began to unspool deep into the hazy afternoon.

Field of Play: 60 Years of NFL Photography is available now.