Long before Cleveland was a city infamous for a cheating scandal involving weighted walleyes, it was a shallow ocean ruled by armored fish that weighed thousands of pounds. The best angler alive could never reel in Dunkleosteus, a fish whose bony face looked like a fanged cybertruck. The fish is considered one of the first vertebrate apex predators, with blade-like jaws that could bite through bone.

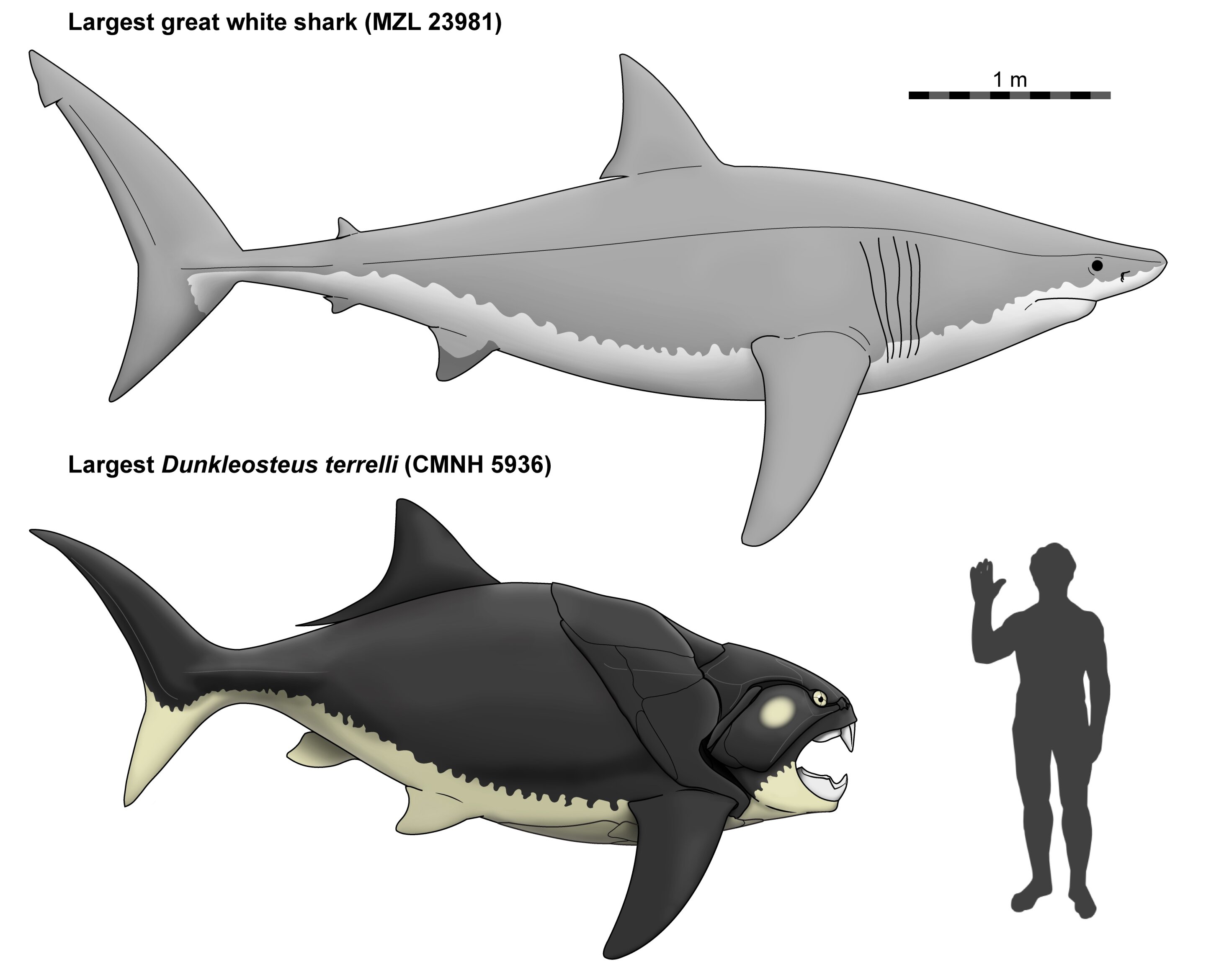

Although modern vertebrates either have skeletons made entirely of cartilage or entirely of bone, Dunkleosteus had a bit of both: a bony head and a mostly cartilaginous skeleton. This peculiar anatomy means the fossil record is littered with Dunkleosteus heads but no Dunkleosteus behinds, so the rest of the fish's body remains a mystery. Some estimates by scientists suggested the ancient fish reached anywhere from lengths of 16 to 33 feet—as long as modern whale sharks. But a new paper published in the journal Diversity suggests Dunkleosteus was much chunkier: "merely" an 11-foot-long fish whose body shape was less fearsome shark and more girthy tuna.

When the paper hit Twitter, many paleoartists leapt at the opportunity to birbify the fossil fish and embrace its newly round form. But outside experts suggested the downsizing is not actually a huge departure from prior reconstructions. "It’s just taking actual data to infer a more realistic proportion for Dunkleosteus," said Sarah Z. Gibson, a paleoichthyologist at St. Cloud State University in Minnesota who was not involved in the new paper, wrote in an email. She added, "It's still a big fish! We can't take that away from it!"

"It's still kind of an oval shape, a little more squat than previously thought," said James Boyle, a paleobiologist at SUNY Buffalo who was not involved with the new paper. Boyle sees the new paper's proposal as "perfectly defensible," especially considering past reconstructions of Dunkleosteus were based on far less rigorous statistical analysis, he said.

The new paper's sole author, Russell Engelman, is a graduate student at Case Western Reserve University, and his prior research largely focused on fossil mammals. But Engelman's Cleveland roots endeared the local fossils to him—an exquisite medley of arthrodire placoderms, extinct armored fish that lived in the Devonian Era more than 360 million years ago. "I’ve known about Dunkleosteus for basically as long as I can remember," Engelman wrote in an email.

The pandemic prevented Engelman's lab group from conducting fieldwork abroad or examining collections in major museums, so he sought out smaller projects. Luckily, the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, home to some of the best-preserved Dunkleosteus skulls in the world, let him in. Engelman remembered chatting with Amanda McGee, the head of the museum's vertebrate paleontology collections, about one of the mounted Dunkleosteus heads in the museum that was suggested to have come from an 18-foot-long specimen. The estimation seemed suspicious; "a fish that big couldn't fit in this room," Engelman thought to himself.

Although remains of the fish were first discovered in 1867, most of what scientists know of the species comes from work published in 1932 by the paleontologist Anatol Heintz, Boyle added. The paper was so good, in fact, that "very few people have actually gone back and explored more about that organism, because it was so well-done," Boyle said. "But now it's been, like, 90 years."

Engelman knew the existing estimates of Dunkleosteus's size were based on parts of the fish's mouth. He tried experimenting with models that relied on head length, expecting the estimates would be similar to those produced by the mouth model. But the head estimates predicted a Dunkleosteus less than half as long. Engelman decided to use a specific modeling approach based on a fish's orbit-opercular length, or OOL—roughly the distance between the eye and the gill chamber. This length is often indicative of body length; consider the pike, a long, sleek fish with a long, sleek skull, or a piranha, a short fish with a short skull.

There will always be exceptions to this rule, such as the long-snouted and short-bodied seahorse, Gibson said. But in general, this strategy of size estimation "can be useful, particularly when there’s no other data to go off of, as is the case with Dunkleosteus." And scientists will only be able to ascertain how robust this new method is when someone stumbles upon a full-body fossil of Dunkleosteus with preserved cartilage, she added.

Engelman applied this model to a large dataset of modern fishes, and Boyle said he wished the new paper had incorporated more ancient organisms that did happen to fossilize in full-body forms. "The modern-day stuff is only a tiny snapshot of the diversity of life as it has been over Earth's history," Boyle said. "There has been lots of time for things to change and be odd and maybe for the sample we have today to be quite biased relative to the arc of history."

Engelman said he would have liked to include more data from fossil fishes, but the pandemic severely limited his access to them. "My bigger concern was that if the method didn’t work on the vast diversity of modern fishes, it would be unlikely to work on Dunkleosteus," Engelman said. He also added that arthrodires like Dunkleosteus, although long extinct, have more similar body forms to living fishes than some other groups, making them a safer test case for the method. Gibson said she would like to apply the method to the Late Triassic fishes she researches to see if they follow the trend.

The extinct arthrodires were long dismissed as an evolutionary offshoot—a weird group of fishes that left no living relatives. But over the past 15 years, fossil discoveries in Southern China have revealed missing links between arthrodire placoderms and modern bony fishes like sharks and rays, making the group more evolutionary relevant than previously thought, Boyle said.

Good science is an act of revision, and as my esteemed editor Barry once wrote, the most exciting thing in science is when we find out we were wrong. The shrunken Dunkleosteus does not significantly change our understanding of the fossil; rather it changes our fantasies of the most menacing version of the fish, Gibson said. Relative to other fossil fishes, Dunkleosteus gets outsized attention because of its reputation as a fearsome predator, Boyle said. This also influences illustrations of the fish that depict a ferocious grin full of jagged blades. But it's unclear if a swimming Dunkleosteus would even show its toothy blades. "They might look perfectly docile," Boyle said.

Besides, squat does not mean sluggish. The new Dunkleosteus looks a lot like a tuna, which at least one conservation group deemed the Ferrari of the ocean, able to zip through the water as fast as 43 miles an hour. Now that's impressive! How fast can Charles Leclerc run without his car? I, for one, feel glad to be living in the age of Chunkleosteus—just as fearsome, twice as relatable.

CORRECTION (5:45 p.m. ET): An earlier version of this story misattributed a number of quotes from James Boyle.