I read a lot of press releases about new scientific papers for my job. Sometimes the art that accompanies them is funny, such as this unapologetically fuchsia rendering of the microscopic creature Saccorhytus. Sometimes they are evocative of a past world, such as this reconstruction of a 100-million-year-old crab. Sometimes these images are ambitious infographics or unsettling acts of Photoshop. Ostensibly, the purpose of these images is the same—to invite people to click on a story about something new we have discovered about the world.

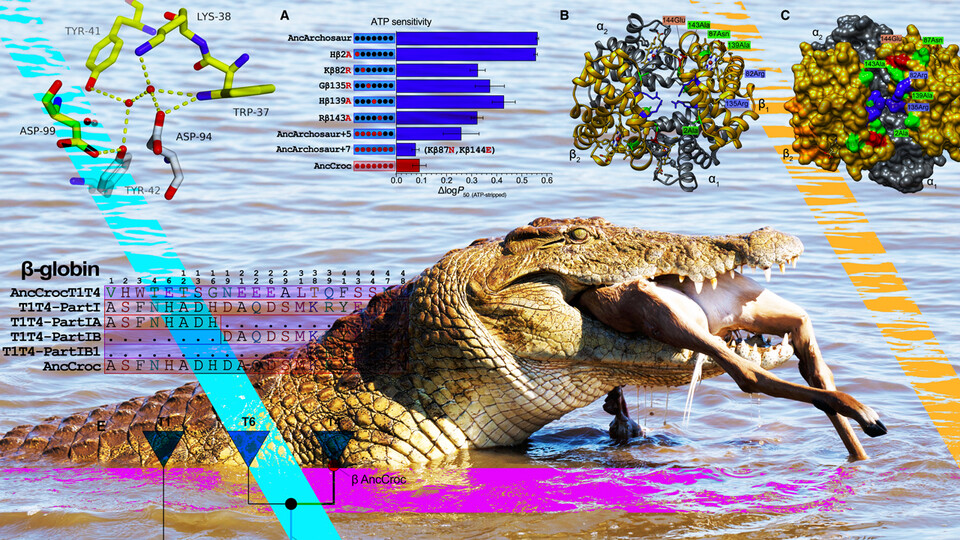

On Thursday, scrolling through press releases, I saw an image that stopped me in my tracks. On one level, it was a photograph of a Nile crocodile rising from the water with half of an ungulate known as an impala dangling from its teeth. But it was also an artistic collage of rendered molecules, charts, and three neon lines streaked through the water where the crocodile had just made its kill. These visual details were so striking that, in my first viewing of the image, I nearly missed the half-swallowed impala, its delicate carcass one part of an image that contained multitudes. It was as if the crocodile had teleported to the 1990s to hunt amid the famous teal carpet of the Portland International Airport. Sure, I wanted to click. But the image also did what great art is supposed to do: It made me think. I wanted it on a t-shirt.

I saw the image on a site called Phys.org, which aggregates science and technology news. It accompanied a press release, "Study clarifies mystery of crocodilian hemoglobin," which spotlighted the results of a new study in the journal Current Biology published by a group of scientists including Jay F. Storz, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The press release was written by Scott Schrage, a science writer at the university. But who had created the image? When I found the image on the University of Nebraska's newsroom—Nebraska Today—I saw the image credit: "Shutterstock / Current Biology / Scott Schrage | University Communication and Marketing." Scott Schrage! Writer and artist. I needed to talk to him.

Schrage, who has been writing about the university's research for about seven years, is responsible not just writing about the scientific papers that come out of the university, but also for finding images to accompany them. Sometimes this secondary task is easy, a matter of sending Storz and a colleague to pose with penguins at the Omaha Zoo to promote a new paper on the evolution of penguin hemoglobin. (Storz is really into hemoglobin. His team made headlines for capturing the highest-dwelling mammal, the yellow-rumped leaf-eared mouse, which lives at heights above 22,000 feet, where there is just about 44 percent of the oxygen available at sea level.) But there won't always be a penguin or yellow-rumped leaf-eared mouse nearby for a photoshoot, meaning Schrage has had to innovate.

"As you're wading through these giant seas of text in like a 15- or 20-page paper, there are these beautiful little islands of visual engagement," Schrage told me, referring to the charts or renderings often included in a paper. "They're sort of delving into some technicalities that are beyond the scope of the story that I'm planning to write, but they're just so, you know, pretty," he said. So Schrage began experimenting, creating images that combined a paper's visual components along with stock photography.

Storz told Schrage he had always been interested in footage of crocodiles found in nature documentaries: seeing the big reptiles lurk below the surface, thrash out of the water, and drag their prey underwater to drown them. This style of hunting meant the reptiles would have to hold their breath for an extraordinary amount of time, even more than an hour. Crocodiles can do this because they evolved a specialized way of regulating their hemoglobin, a "slow-release mechanism that allows crocodilians to efficiently exploit their onboard oxygen stores," Storz told Schrage for the press release. (To learn more about the new research, you should definitely read Schrage's story, which is much more thorough and nuanced than this one.)

Schrage began looking for stock photos of crocodiles ambushing their prey in the water. "This particular image I just thought was incredibly captivating," he said. "It's obviously like, deadly serious. But it's also kind of cartoonish." The dangling legs of the impala reminded him of Tom and Jerry cartoons, how a tail dangling from Tom's mouth might have been the only hint that Jerry was in trouble.

The stripes came next. "I felt like I needed something to frame the croc," Schrage said, adding that he arranged the stripes to be reminiscent of an evolutionary tree. He turned to a color palette of the '90s. The teal stripe came first—reminiscent of the colors of the Charlotte Hornets, he noted—and then an orange creamsicle, and then a fuchsia stripe at the bottom. Schrage often tries to include the University of Nebraska-Lincoln's customary red in images, but he worried, in the context of a watery hunt, blood red might be too on the nose. Besides, a crocodile's hunt isn't necessarily a bloodbath. "It's drowning, it's doing its death roll in its prey," Schrage said. "More or less, especially with prey like an impala, it's just swallowing it."

Schrage overlaid the image with figures from the study: some charts and renderings of resurrected hemoglobin from the ancient ancestors of crocodiles. He also included an actual phylogenetic tree from the paper in the bottom-left corner. "As I was looking at these, I was thinking, OK, these kind of look like childlike, really rudimentary representations of crocodile teeth," Schrage said. "So I was like, OK, let's include that element as well."

All combined, these elements make for a thoroughly unforgettable scientific image. When I asked Schrage if he considered himself a maximalist, he demurred. Institutional writing often comes with guidelines, many editors, and many eyes that want a say in what's published. "But when I pull together an image like this, I let my flag fly a little bit," he said. "When it comes to this, I do have more freedom."

Schrage said he feels lucky to cover this kind of research. Reconstructing hemoglobins that are hundreds of millions of years old almost almost seems like science fiction, he said. And I feel lucky to encounter Schrage's work and this particular image, which feels like a science communication hallucination—an image that made me gasp, my own, humble hemoglobin scurrying throughout my bloodstream.