Heidi Clements jolted me out of a glaze-eyed scrolling spiral one night a few months ago. A typical video of hers starts with her bending over toward her camera and then stepping back to reveal her starting point, a bra and pants. Then she builds an outfit while a voiceover shares a funny or heartbreaking or inspiring nugget of wisdom, like "If you don't ask for what you want, you probably won't get it," and "You may say you have nothing to wear, I say: just get dressed. Even if you have nowhere to go, just get dressed. Even if you don't like how your body feels right now, just get dressed."

Clements has amazing style. It's androgynous and playful, a little punk, a little Stevie, California-easy with a heavy silver chain or a black leather bag. Her arms are covered in tattoos, and she has a shaggy haircut I've been trying to learn to cut via internet videos. Her nose is pierced with a silver hoop and she loves a red lip. She's an influencer; she has more than 600,000 followers on both TikTok and Instagram, and her manager's information is in her bio.

She's also in her sixties. The wrinkles on her face reflect her age, because she's never had Botox or fillers. Her hair is gray. And those inspiring nuggets she shares are often part of larger meditations on aging. In a recent video, she talks about the hot flashes, yes, but also anxiety, tooth loss, and vertigo that came with menopause: "Do I say this to scare you? No. I say this to prepare you. Know what's ahead and embrace it now, get loud about it now. Women should never fade into the background when they hit midlife."

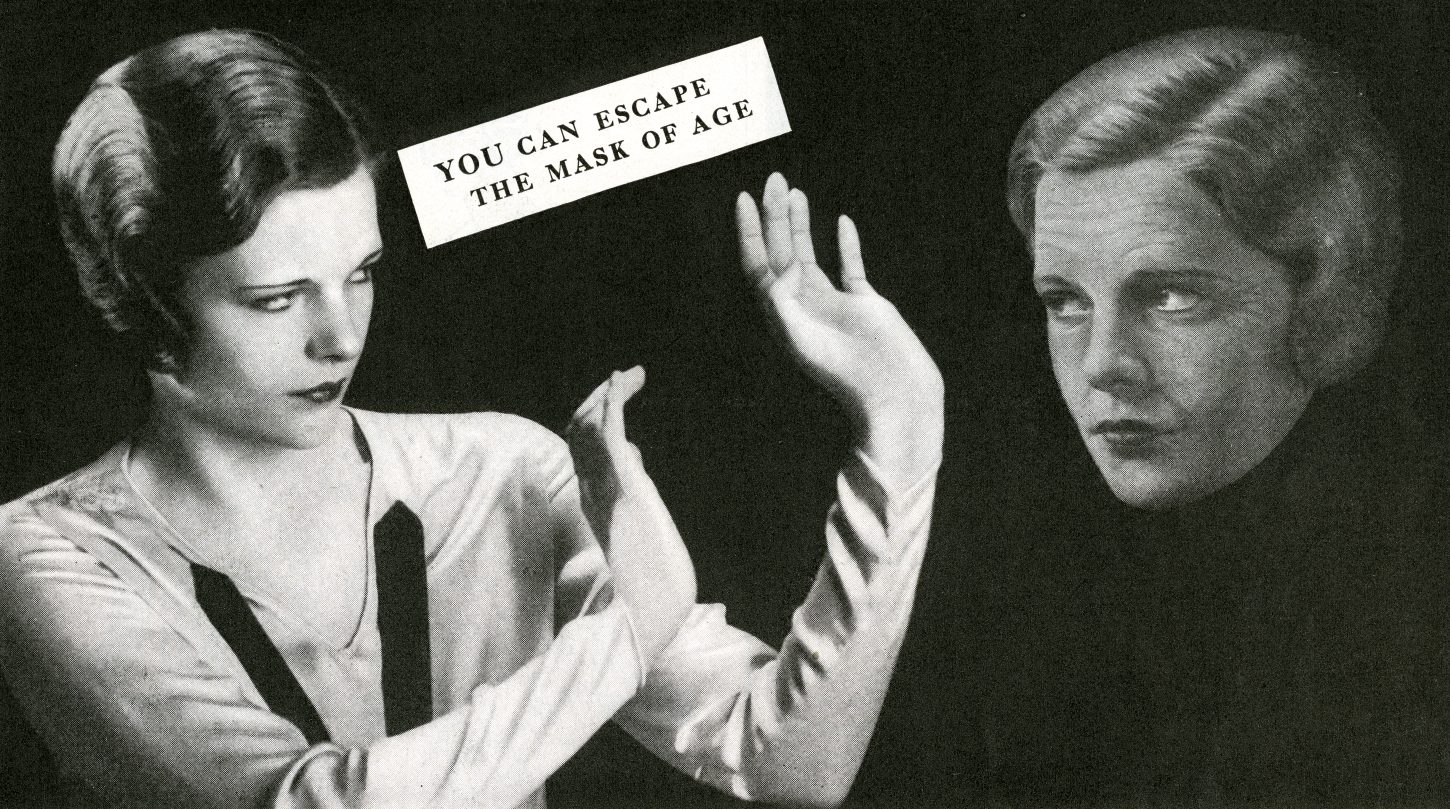

To call Clements's social-media body of work radical would be an understatement. In the past two years, she has created a space of her own inside an industry dominated by an obsession with youth. The influencer industry, with its profligate use of injectables and filters, is a concentrated microcosm of broader American culture. If the richest, thinnest, whitest among us are terrified of fine lines, what hope is there for the rest of us? American women are taught to fear aging above nearly everything else: To no longer be young, tight, bouncy, and sexually viable is to be devoid of value. As a woman in my thirties, I hear whispers of "invisible woman syndrome," a phenomenon that describes how women come to feel invisible in public as they age, and I wonder when it'll come for me.

The jealous, bitter crone haunts her younger counterparts in pop culture from the evil stepmother in Snow White to The Substance's Elisabeth Sparkle. She's envious of the younger woman's beauty, but also of her potential, and that is what has always terrified me about aging. It's easy to look forward to the future; much harder is living with the choices you made when you were a different version of yourself, with different priorities, values, and facts to work with. The bildungsroman is a simple narrative to wrap your head around, but what happens after?

Influencers like Clements are a refreshing reminder that women's lives don't end—and needn't end—at 50. Not only can they eschew beauty norms around aging, but they can command your attention while they do it. Clements constantly reminds her audience that she is still in progress, still learning, still evolving. It's given me a lot to think about in relation to my own aging process.

Last week in Atlantic City, I stood watching at a blackjack table with my Defector colleague Kathryn. I was startled when a security guard waved a hand into my field of vision and apologetically asked if she could see our IDs. I was a few days shy of my 33rd birthday and pleased to be considered potentially underage alongside our youngest staff member. I went on to brag to the other Defector staffers, who congratulated me. Later, when I was alone, I thought about that moment some more. I don't know when I started to take being carded as a compliment. It's one of the many parts of aging that have snuck up on me quietly, along with the back pain and the nearsightedness.

When I was younger, I thought aging would be an instant transformation: One day I would wake up with my hair magically cut into a sensible short style, I'd trade my leather boots for orthopedic sneakers, and I'd be happy to sit out on the culture, conversations, and trends that young people are into. In this simplistic fantasy, my curiosity would fade, as would my sense of style, my ambition, even my anger. Old age for me would be a wave of unchallenged contentment that came with my 50th birthday and rendered me invisible forever.

This is absolutely ridiculous, of course. If you're lucky enough to keep your hair, it will gray little by little. If you lose touch with culture and politics, it will be the consequence of millions of tiny choices you make about what you pay attention to over the course of years. I've learned this as I've entered my thirties and watched peers refuse to move on from cultural touchpoints of our adolescence.

Earlier this year, there was a bizarre trend on social media of millennial women freaking out about the length of their socks; apparently, Gen Z is wearing taller socks and making fun of millennials' ankle socks, which caused millennials to have absolute meltdowns.

Every sock video annoyed me, because they betrayed an attitude toward adaptation that I find depressing. First, they held onto an aesthetic trend from their youth and stopped paying attention to how these things shift. Sweeping generalizations about trends like this only happen after they've had plenty of time—sometimes even years—to marinate in the culture. By the time it's a TikTok trend, it's been in the air for a minute. The second reason this annoyed me was that once these people realized they had been ostriching sock length trends for a decade, they were offended that the trends had moved past them and acted like it happened out of nowhere. Then they'd film themselves putting on tall socks and cringing because it didn't feel right. Either care about these things or don't! Performing an anxiety of aging does numbers though, maybe because millennials as a generation are still relatively young and having our first go at feeling out of touch.

I can't imagine Clements would make a video asking her audience if her socks were acceptably tall, because she seems to have a clear enough sense of her own identity not to need strangers to affirm the fashionability of her sock length. That is what makes her so compelling to me. You could put her outfits on a 25-year-old girl in the Lower East Side and they would totally make sense, but it's not because she's trying to look young. She's simply kept her eyes open and allowed her conception of self to evolve as she aged.

For most of its existence, the internet has been the domain of the young, the tech-savvy, those literate in the bleeps and bloops that compose our increasingly digital world. That's even more true of the influencer world, where you can never really be sure the poreless face you're seeing is real. As the industry continues to grow, and as the people using these platforms age, I look forward to seeing more versions of later life that are defined not by bitterness but by honesty, curiosity, and joy.