In April 2018, the underwater photographer Ryo Minemizu watched as a creature the size of a ladybug bobbed around 50 feet underwater off the shores of Okinawa, Japan. The thing resembled a jellyfish, a yolk-like center with trailing, wispy tentacles. Minemizu posted photos of the creature to social media, but no one could decipher the mysterious swimmer. They couldn't even sleuth out its phylum, a taxonomic category ranked just below kingdom, meaning it is incredibly broad (examples of phyla include arthropods, mollusks, and chordates). But now, in a paper recently published in the journal Current Biology, a team of scientists say they have identified the strange creature, which is actually not one individual animal but 1,020 parasitic worms clutching each other in a tight, blob-like posse. As far as parasitic pageantry goes, this may rank up there with the Leucochloridium paradoxum worms that turn snails into psychedelic zombies (more on that in a minute).

Minemizu collected a single sample of the animal and bottled it in formaldehyde so that researchers could study it. The scientists examined the tiny specimen under a microscope to find the jellyfish was made of two types of cercariae, which are the larval forms of parasitic worms called trematodes. Trematodes have some of the zaniest life cycles of any creatures on the planet, as they typically have to pass through two different hosts to complete their life cycle. But it's a wide, wide world with no guarantee a puny parasite will encounter both its target hosts, so many have developed utterly bizarre strategies to attract their attention. For example, the pulsating Leucochloridium paradoxum larvae wriggles to the snail's eyestalks, replaces them, and begins pulsating to make the snail more obvious prey to a host.

Trematodes begin life as eggs, often released in the poop of a bird, mammal, or fish. Then the egg hatches into a hairy salami-like shape that swims through the water to find its first host, perhaps a snail. Once the salami has found the snail, it burrows into the snail's body and then clones itself into the free-swimming cercariae, which are often ejected from the host and swim around in the water in search of a secondary, often bigger host, such as a bird, fish, or mammal. The cercariae's goal is often to be eaten by this third and final host so they can reproduce sexually inside their body and lay fertilized eggs that are then released by way of poop. Ah, the convoluted circle of life!

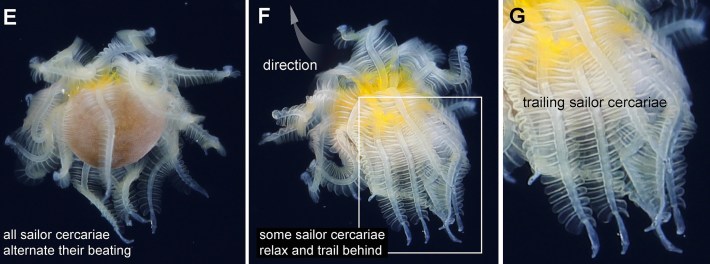

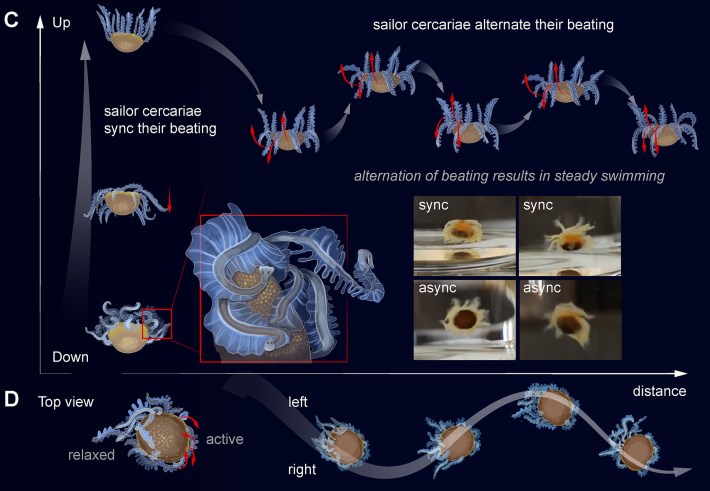

In the case of the mysterious creature from Okinawa, the scientists discovered jellyfish-shaped aggregation was formed by two types of cercariae: large, tentacle-like "sailors" and tiny "passengers." The specimen contained more than 1,000 passengers arranged in a hemisphere, with the much bigger sailors anchored to the flat side, waving their tails like the snakes on Medusa's head. These large sailor tails wiggled in unison to help the whole worm blob to move. If the sailors beat their tails in synchrony, the blob pulsed or jumped. If they beat their tails asynchronously, the blob jetted around smoothly. Before it was preserved, the worm colony had a yellowish, yolky color inside the tentacle-like sailors, and a brownish color inside the many, many passengers.

When the researchers sequenced fragments of the worm blob's genome, the closest matches were in the Pleorchis, a genus of trematode worms. But the species is unknown.

Is 1,020 worms gathered in the approximate shape of a jellyfish a sign eerily reminiscent of a biblically accurate angel? Perhaps, but it is more certainly a sign of evolution, an example of a number of creatures mimicking prey to increase their chances of being eaten. The researchers suggest the swimming colonies of worm larvae copy the movements of small plankton worms. This charade is popular amongst other species of trematode larvae, some of which have developed extraordinarily long tails. Another horrifying larval trematode strategy called—I shit you not—"Rattenkönig" occurs when a group of worms join together by their tails, forming a squirming pinwheel reminiscent of a rat-king. (You can gaze upon the horror of a Rattenkönig worm blob here, or you can live the rest of your life in perfect peace.)

Joining together in a jellyfish-like blob certainly helps the hundreds of worms swim around. But the researchers suggest this aggregation may offer other benefits, such as increasing the number of parasites swallowed in a single gulp and ensuring the worms make it to their correct host (smaller fish would not be able to swallow such a robust blob). The researchers note that polymorphism, or multiple forms existing for one species, is rare in parasitic flatworms. So the two distinct sailors and passengers that congregate into this jellyfish-like aggregation is a new case of such divergent forms in a single trematode.

As the researchers examined the passengers, they found "well-developed penetration glands" that would allow the larvae to invade the tissues of its host. But the larger sailors had no such penetration organs, which renders their ultimate destiny a mystery. Are these large wiggling sailors sacrificing themselves to help ferry hundreds of passengers to their final destination? This scenario would mean the baby worms adhere to a strong division of labor, similar to the specialized castes of various insect species. Or do the sailors forgo wriggling into specific host tissues to reproduce and instead mate in one huge orgy in the digestive system? Orgies can happen anywhere, so why not the stomach?

We have no answers to these questions now, begging a larger question: Do we ultimately need them? The sea is full of mysteries, and many things are not what they seem. Some tiny bobbing creatures are baby jellyfish, and others are unsettling parasitic-worm–castes united by the overwhelming desire to be eaten and ultimately shat out. Tag yourself!