On June 25, 2023, four volunteers entered a simulated Mars habitat located in a hangar at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. Yesterday, they finally emerged. The four—a commander, an engineer, a medic, a scientist—spent 378 days, or roughly the length of time a crewed Mars mission would dwell on the surface—inside the habitat living as Martian astronauts would, in order to study the behavioral and medical effects of isolation. I submit that if NASA really wanted to game for a worst-case scenario, they would put me in there.

This was the first of three Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog (CHAPEA) missions to evaluate the technology and protocols for an extended surface stay, and the crew performed the same scientific and technical duties they'd be expected to on Mars, while simultaneously undergoing constant physiological and psychological testing. The idea is that NASA wants to spot potential issues before the astronauts are actually stuck on Mars. If they're serious about this, I urge them to put me on the next CHAPEA crew, because I am likely to cause all sorts of issues, and I have zero useful skills to balance that out. If we're going to be testing the crew, let's really test them, you know?

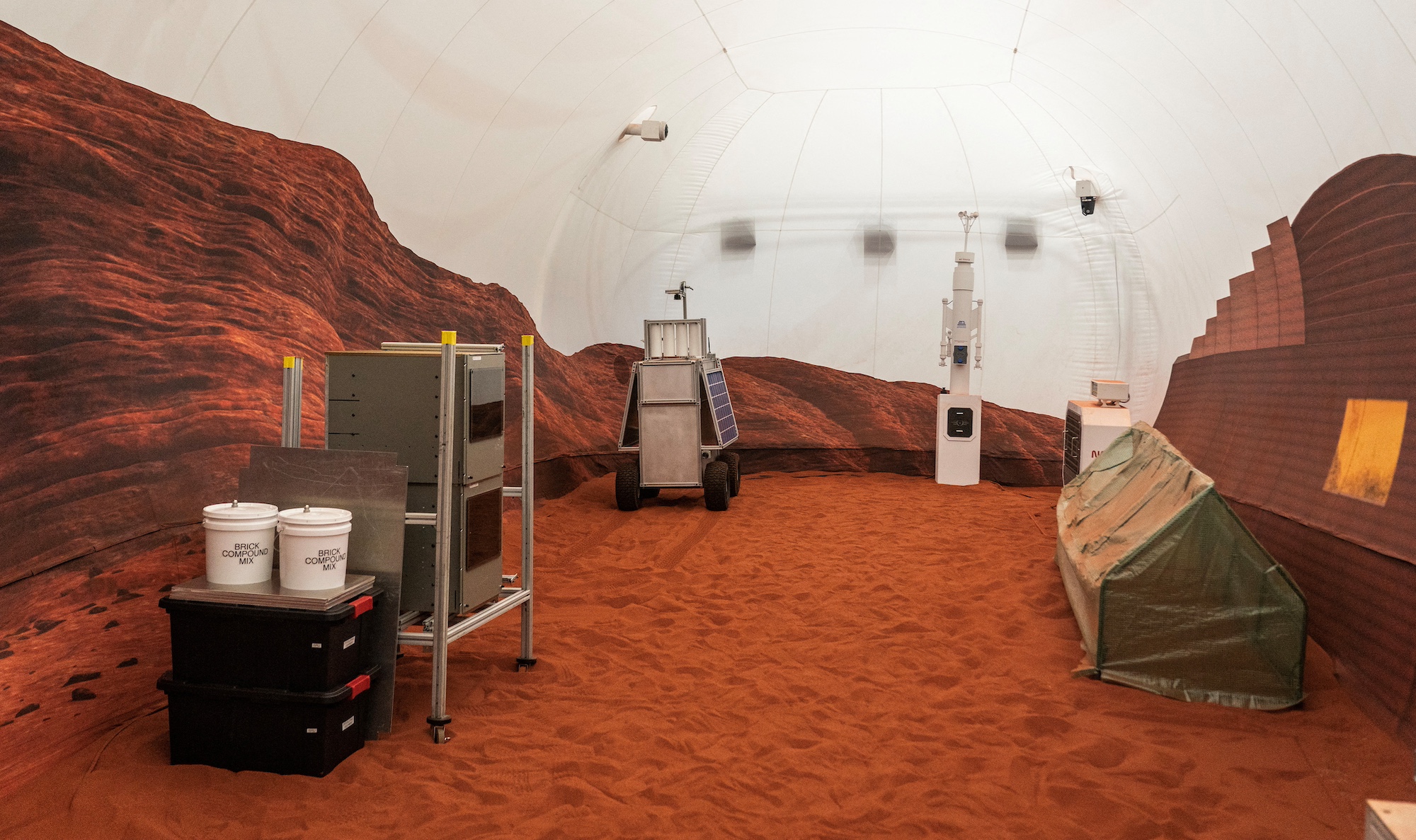

The habitat, Mars Dune Alpha, is itself a nifty bit of technology. It was 3D printed in one month, just as a real Mars habitat might be made of compacted Martian soil and built by a fully automated process before astronauts arrive, because it's a lot easier and more cost-effective to send up a 3D printer than it would be to ship an entire building. My vow to NASA and to the pursuit of science itself is that I would screw up the structure somehow, possibly by slamming a door so hard a piece of it falls off, exposing the inhabitants to the elements and a rapid death. This is why it's important to simulate this stuff on Earth before they try the real thing.

The base features a work area, a communal living and kitchen area, a bathroom, a medical bay, a communications center, an exercise room, and even a space to hydroponically grow fresh vegetables. NASA considers diet one of the most important things being examined with CHAPEA, because other than the limited tomatoes and leafy greens that can be grown within, astronauts will be restricted to packaged meals. "Menu fatigue" is a real thing, and I have no doubt I would start vocally suffering from it within a week of the start of the mission, annoying everyone else by complaining about yet another freeze-dried dinner, and nearly violating containment by attempting to Doordash a pizza before being banned from using the base's communications equipment.

Mars Dune Alpha also contains four separate, private sleeping areas—NASA considers giving astronauts a place where they can be alone among its highest priorities to maintain healthy social dynamics. I would ruin those dynamics. I would insist on hanging out in my buddies' rooms until late into the Martian night, telling them about funny tweets I saw or trying to get them to play Mario Kart with me. I would fail to read their increasingly unsubtle signals that they wish I'd leave them alone.

Just outside the base, on the other side of a real airlock, is a mock-up of the Martian surface, for the purpose of simulated Marswalks. I would absolutely forget to wash my space suit right after my Marswalks, and it would get all nasty and grody and everyone would hate me. If NASA's not prepared to deal with my shit now, in a simulation, it certainly won't be prepared for it on Actual Mars. The same could be said for my constant off-key singing while using the bathroom. This is the kind of stuff they don't teach in space school, but which I can offer.

I promise I will panic in any emergency, simulated or real. I vow that I will shirk my responsibilities, and require my crewmates to pick up my slack. My hygiene will be questionable at best. Also I would smuggle my cat in.

Contingency planning is something NASA does better than anyone. In this way, me being an absolutely nightmare of a human to be around is much like an unexpected solar storm, in many ways: If something can go wrong, it might—and there has to be a way to fix it. The only way to be absolutely sure that a Mars mission has planned for every emergency is to stick me in there.

Here are the requirements for CHAPEA crew applicants:

- Be a U.S. citizen or permanent resident

- Be within the ages of 30-55

- Possess a master’s degree in a STEM field, including engineering, biological science, physical science, computer science or mathematics, from an accredited institution.

- Have at least two years of related professional experience in a STEM field or at least 1,000 hours pilot-in-command time on jet aircraft.

- Be able to pass the NASA long-duration flight astronaut physical.

Two out of five ain't bad. I think NASA should waive the other three, in the name of science. They can ask my exes if they need references for my suitability. Because—well, first watch this video of the crew ending their mission.

CHAPEA's 4-person crew just exited their home after 378 days. ✅

— NASA's Johnson Space Center (@NASA_Johnson) July 6, 2024

They simulated a Mars mission to help assess health and performance in relation to Mars-realistic resource limitations in isolation and confinement. The door is officially open and the mission is complete. Congrats… pic.twitter.com/AbfaMrzw2n

They all seem in good spirits, don't they? Smiling, waving, happy to be out but not desperate? They appear to have gotten along fine with each other in there. But NASA needs to find out what happens when they don't. That's where I come in.