Some might say Robin Ficker hasn’t lived a life well spent. But he’s surely lived a life, well, spent.

That is, Ficker has never wasted a damn day. If the name rings a bell at all, it's almost certainly because of the renown Ficker earned in his role as the most relentless heckler in pro sports history—a guy who so pissed off Michael Jordan that Charles Barkley literally hired Ficker to heckle MJ in the NBA Finals. Ficker was such an ass at NBA games in the 1980s and 1990s that the league promulgated a fan-behavior rule and then named it after him. He’s also a lifelong politician, one whose conduct in the political arena to this day remains at least as disruptive as his screaming in the basketball arena ever was.

Ficker has never gotten attention for doing anything anybody liked. But he’s always liked getting attention, and is still getting lots of it. Last week, just weeks short of his 79th birthday, Ficker was in the news again when a Maryland Court of Appeals panel disbarred him. The ruling revoking his license accused Ficker of various not-especially-significant malpractices as an attorney, including occasionally not showing up for court hearings, and in truth seems like more of a career achievement award than anything else. As the Washington Post reported, the judges held that “Ficker has been the subject of a long history of complaints of professional misconduct that expand over three generations of the bar counsel.” Ficker has lost his law license several times over the years, but always succeeded in getting it back. What makes this disbarment noteworthy is that Ficker happens to be in the middle of the most ambitious campaign of his life.

“There’s no way they should punish an attorney so much for something like this,” Ficker told me, “but they decided to make a statement because it’s me, and because I’m running for governor.”

Ficker says the state’s established political machine is out to get him. He says that the powers that be can't stand that his campaign platform is built around the attention-getting if hard-to-keep promise to reduce the state’s sales tax by $.02. Yet Ficker seemed more amused than upset by the latest sanctions.

“I don’t have to show up for court now!” he said. “This gives me more time to campaign!”

By now, those who follow him—and I’ve been a perpetually awestruck observer of his for four decades—realize that no news is bad news for Robin Ficker.

Ficker’s heckling also used to make lots of news. Some of the biggest names and biggest people in basketball went after Ficker for yelling at them from his seat one row behind the visitors bench at the Capital Centre, the home of the Washington Bullets from 1973 to 1997. Utah coach Frank Layden threw water and spit at Ficker once. Indiana forward LaSalle Thompson spit on Ficker several times. Portland’s behemoth center Kevin Duckworth tried attacking Ficker behind the bench but was restrained before what promised to be an extremely grisly murder could happen. Isiah Thomas threw a shoe and Jordan threw a ball, both in anger. When Charles Barkley heard that Ficker got under Jordan’s skin, he paid for Ficker to come to Phoenix to taunt Michael Jordan from behind the Bulls bench during the 1993 NBA Finals. Ficker waved a copy of Michael and Me: Our Gambling Addiction, My Cry for Help!, a book by onetime Jordan hanger-on Richard Esquinas that alleged the Bulls icon was a compulsive gambler. Inevitably, Ficker also yelled wagering taunts. Among them: "Hey, Michael: How much do you want to bet on the game?"

NBA commissioner David Stern had heard more than enough by then, and set out to neuter Ficker and his imitators. Stern knew that visiting teams had been moving chairs onto the court during timeouts at the Capital Centre. So the NBA promulgated a rule that outlawed “disrupting communication between coaches and players.” Teams were instructed to henceforth give violators of what was dubbed The Ficker Rule one warning per game and then toss them from the arena. Bullets management got the hint that it had better get some distance from Ficker. Owner Abe Pollin also might have been upset by Ficker’s comments as the Bullets were in the process of coming up with a new name. Ficker told me that there’s no way they could choose “Wizards” or “Dragons,” both finalists in the naming contest, because they’d be exploited by racists. “They’re Klan names!” Ficker said, while threatening to show up in a Klan costume at the next home opener if Pollin picked either. History will show that the name Wizards won the rigged contest, and hasn't won much since.

Ficker did not follow through on his threat to don Klan regalia, but when the team moved from the Capital Centre to the downtown MCI Center in 1997, Pollin did not offer Ficker a seat behind the bench or even close to the court. Ficker declined to buy any tickets. Other than the occasional nostalgia gig, Ficker’s NBA heckling days were over, although his time in the public eye was not.

As with his recent disbarment, the end of his basketball deviousness allowed Ficker to devote all his energies to politics. His record as a hyperaggressive ass was already at least as impressive in that arena as it ever was at the Cap Centre. And he's only added to it.

In 2014, I checked the Washington Post archives to see how many stories the paper had run calling Ficker a “gadfly.” There were 56. I rechecked this week: The gadfly count is now up to 82.

It’s hard to pick Ficker’s greatest hits in politics, but his most auspicious political episode came early: Ficker made a cameo appearance in the mother of all American political scandals, Watergate. In 1972, Ficker was recruited to lead a group called “United Democrats for Kennedy,” which was ostensibly a write-in campaign that aimed to draft unwilling candidate Ted Kennedy to run for president. But Kennedy, who was fresh off killing girlfriend Mary Jo Kopechne after driving his car into the Chappaquiddick, wanted no part of the effort. It was a failure, generating only 733 voters wrote-in Kennedy in the Democratic Party’s New Hampshire primary. It later turned out that getting Kennedy votes wasn’t really the group’s main aim. Ficker’s task was actually just to bash the other Democratic candidates.

As Ficker and America both learned during Congress’s Watergate investigation, the New Hampshire primary scheme had been cooked up and financed by the Nixon campaign. "The write-in campaign for Senator Kennedy was totally financed by the Committee to Re-Elect the President," read the Watergate report, "yet that information was never disclosed either to Mr. Ficker or to the public during the campaign."

Ficker was targeted by the now-legendary Dirty Tricksters in the Nixon White House, the exact same folks—Charles Colson, Robert Haldeman, John Mitchell, Jeb Magruder, et al—that planned the Watergate break-in. Nixon speechwriter Pat Buchanan got credit for identifying Ficker as a promising potential stooge after Ficker made local news for political shenanigans in 1971; he’d been arrested for trespassing for handing out campaign literature in a Santa suit, and then made the front page of the Metro section of the Washington Star for making a stink about getting arrested for littering after he posted campaign signs reading “My Friend Ficker” on what seemed like every telephone pole across the Maryland suburbs. Magruder’s memoir, An American Life: One Man's Road to Watergate, noted that Ficker’s ruthless and rule-breaking campaign tactics in Maryland political races made him seem attractive to the ruthless rule-breakers working to get Nixon reelected.

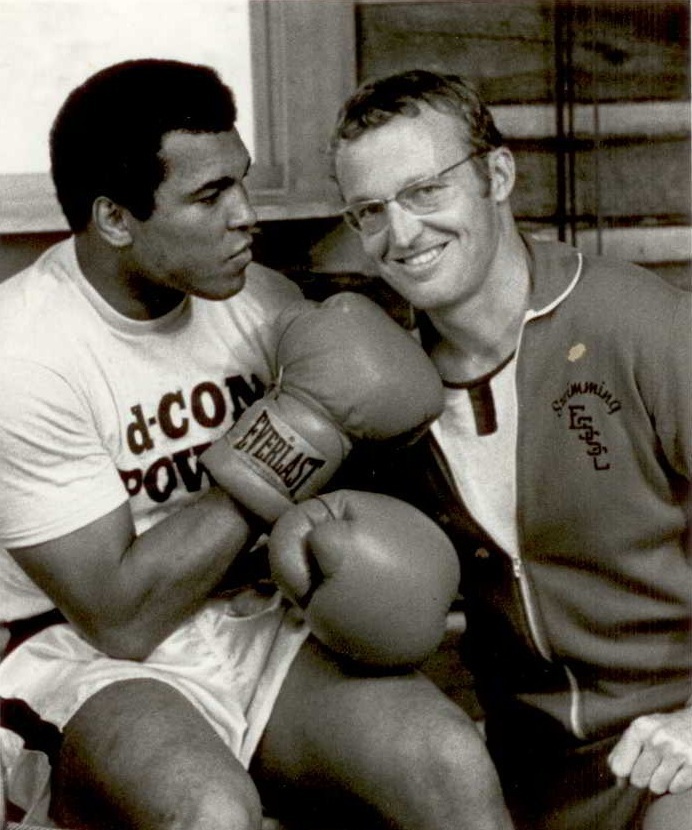

But while all his political and sporting renown comes as a disrupter, every Ficker retropective should also recount the sweet and very cool chapter of his life relating to an unlikely relationship with one of the few guys who even Ficker would admit had a bigger mouth than him: Muhammad Ali.

I first met Ficker around 1989, after years of hearing about his exploits, and he had occasionally referenced his deals with Ali during our subsequent conversations over time. I didn’t take the mentions too seriously. But bizarre as he has always been, Ficker never told me anything I ever found to be untrue. And so, in 2014, on the 40th anniversary of Ali’s iconic Rumble in the Jungle with George Foreman, I called Ficker up to ask what the deal with The Champ was. Ali was his hero, Ficker said, and is the guy he either credits or blames for inspiring him to a life spent taking public stands and being loud about it. Ficker was also a fitness nut; his daughter, Desiree Ficker, ranked among the top triathletes in the world for years. Ali always spent a lot of time in Washington, D.C., and Ficker learned that the champ would stay in shape during visits by taking early morning runs in Greenbelt Park, a national park just outside the city. One day in the mid-1970s, Ficker got up before sunrise and drove to the park, hoping for an Ali sighting.

"And there he was, getting ready to run," Ficker told me.

Ficker asked if it was ok to join, and Ali said yes. Ficker showed up the next day, and ran with him again, and then the next. When Ali was getting into his limo on a day he was heading out of town, the Champ recited a poem he’d made up on the spot: "I like your looks. I like your style. I'll give you a call in a little while."

And Ali followed through. For the next several years, Ficker was a frequent guest and workout partner at Ali’s Deer Lake training compound. Ali would let Ficker sleep in the big bed, and the champ would take a cot in the cabin where his sparring partners and seconds rested.

"He treated me better than any son,” Ficker says.

Ficker says Ali asked for nothing in return other than to have a partner in his morning runs through the Pennsylvania countryside.

He’s got photos to back all the Ali tales up, too. It’s jarring to connect the Ficker that inspired NBA folks to spit on or throw things at him with the guy loitering around a cabin with Ali—with The Greatest! Muhammad Ali!—and his family. If Ali was so nice to Ficker, what have the rest of us been missing?