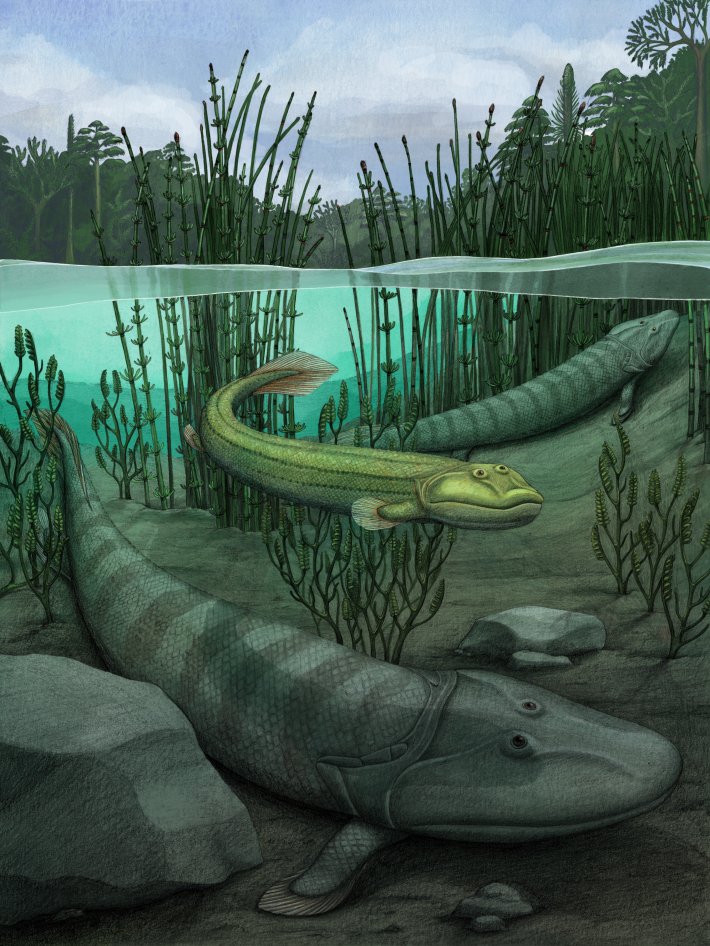

About 375 million years ago, ancient fish took their first awkward steps in the shallows and toward land. Their fins evolved distinct adaptations, becoming less like fins and more like limbs. And some of these lineages of fish would boldly go where no fish had gone before, or at least where few fish had gone before, and over millions of years would make way for vertebrates to trample the lush realm of the terrestrial world and forever alter the course of evolutionary history by inventing sorbet (whee!) and the health insurance deductible (boo!).

Around the same time, other fish stayed put. They may even have started evolving toward life on land without ever truly leaving the water, developing arm bones and musculature distinct from traditionally fan-shaped fish fins that might have helped them prop themselves up in the shallows. But at some point, these fish evolved in a different direction, eschewing the ground and all kinds of bottoms for life in the open water. They kept on swimming. Unlike their famous cousins, these fish would not be some of the first colonists of the terrestrial world. Instead, they would remain in water and mind their business. Why uproot everything for a chance with land when you had a good thing going?

Now, in a paper published Wednesday in the journal Nature, a group of scientists have described a new species of ancient fish, Qikiqtania wakei, that did just that. Although the Qikiqtania (pronounced "kick-kiq-tani-ahh") is closely related to Tiktaalik, the nine-foot-long star of the water-to-land transition, Qikiqtania's fins appear much better suited for paddling than walking. And the single specimen of Qikiqtania is much littler—about as long as a Chow Chow.

For us humans, it can be tempting to think of evolution as a path toward more complex, "better" species, according to Sandy Kawano, a researcher at the George Washington University, who was not involved with the new paper. "There is a classic image of humans evolving from apes that is often misinterpreted to mean that evolution is a 'march of progress,'" Kawano wrote in an email. But evolution is extremely non-linear, and encompasses a bunch of animals doing many different, specialized things. "It's not just an ancestor that kind of was halfway out of the water," said Tom Stewart, an evolutionary developmental biologist at Penn State University and an author on the new paper.

As terrestrial organisms, we humans can bring our own bias into thinking that land is the place to be for anyone with a backbone. While some lineages kept evolving to move onto land, other lineages continued specializing in new ways in the water, according to Richard Blob, an evolutionary biologist at Clemson University who was not involved with the research. Qikiqtania "gives a richer picture of the diverse lifestyles and body plans that existed when the first vertebrates moved onto land hundreds of millions of years ago," Blob said.

The single specimen of Qikiqtania was first unearthed in 2004, less than a week before the same group of scientists would uncover Tiktaalik at a nearby site. The team of paleontologists, which included Neil Shubin of the University of Chicago and Ted Daeschler of Drexel University’s Academy of Natural Sciences, had come to the Canadian Arctic for the sixth year in a row hoping to find a fish on the cusp of limbs. While eating lunch near camp, Shubin, an author on the new paper, looked down and saw "a field of scales," he said. He'd stumbled upon parts of a fossil fish: jaw parts and scales embedded in stone. One rock, about the size of a brick, had just a couple of scales on the outside, and Shubin debated leaving it behind. "Do I want to take a whole block back, you know, just for a couple scales?" he thought, before deciding: "What the heck. Sure." The team returned to the site to fully excavate the fish later that afternoon. But days later, the team found specimens of Tiktaalik and poured all their efforts into describing a fossil that would become famous for filling the evolutionary gap between fins and legs.

More than a decade after Tiktaalik was described, and in the months before the spring of 2020, Stewart and Justin Lemberg, at the time postdocs at the University of Chicago, were scanning some old specimens from the Tiktaalik expeditions. On March 13, Stewart and Lemberg scanned an inconspicuous brick-sized stone with a few scales. "There was no assumption that there was anything else there," Stewart said.

But the initial CT scan revealed an image that no one was expecting: "There was this beautiful fin inside," said Lemberg, a paleontologist who is currently doing cultural resource management fieldwork in California and is an author on the new paper. The fin looked different from Tiktaalik's, but the scan was fuzzy, creating a dizzying number of possibilities. Maybe the fin belonged to a baby or adolescent Tiktaalik. Maybe it came from another species, or even another genus. "That was the thing we were desperate to look into," Lemberg said. But within days, the university shut down for the pandemic, barring everyone from the bulky and extremely not-portable machinery needed to get better scans of the block.

In the summer of 2020, the researchers returned to campus. Determined to get a clearer image, Shubin conducted a masked hand-off of the block to a professor on campus who sawed off excess parts of the stone around the fin. After months of data processing, which initially involved Lemberg transporting a gargantuan PC to his personal home, the new scans crystallized to reveal an intact, three-dimensional pectoral fin and a boomerang-shaped humerus that looked utterly unfamiliar to the scientists.

"When I saw the illustrations of the Qikiqtania wakei fossils, my jaw dropped," said Kawano, who added that she has "an unhealthy obsession with the humeri of tetrapodomorphs." Qikiqtania's humerus was L-shaped like the arm bones of other early tetrapod-like fishes like Tiktaalik. But whereas the humeri of all these other fishes boasted ridges and crests that would support pectoral muscles needed to prop up a body or waddle on the ground, Qikiqtania's humerus was eerily smooth. "It looked much more like a fin than an arm," Lemberg said.

On the tree of life, Qikiqtania's sits above a creature like Eusthenopteron, a fully aquatic Devonian that has a prominent ridge on the underside of its humerus. So Qikiqtania's evolutionary placement shows it lost such ridges. And while Qikiqtania's close relatives Tiktaalik, Panderichthys, and Elpistostege all had fins and girdles adapted to propping themselves up on the ground, Qikiqtania's fin was clearly adapted for swimming, implying the fish returned to the open water.

"What we're showing is this boundary between water and land is actually very porous," Shubin said. "Creatures are going back and forth."

Alice Clement, an evolutionary biologist and paleontologist at Flinders University in South Australia who was not involved with the research, said "the CT work is beautiful" but that she was cautious in interpreting the lack of ridges on the humerus as an indication that Qikiqtania returned to the water. "This can only really be conclusively confirmed with the discovery of additional material," she said, noting the species is described from a single specimen and humerus.

Qikiqtania's name, which is derived from the Inuktitut word for the region where the fossil was found, was selected with the help of Sylvie LeBlanc, a territorial archaeologist with the Nunavut cultural ministry. And just like Tiktaalik's fossils, Qikiqtania will be returned to Canada in a few months. Stewart added that the raw data and models from the paper will be publicly accessible. "It helps the science being able to share this data with everybody who needs it and wants it," he said.

As with any fossil discovery, Qikiqtania raises new questions about the vanished world it inhabited. Kawano suggested comparing Qikiqtania's fin to the fins of living fishes to better understand how the fossil fish would have moved in real life. Shubin still dreams of learning more about the creatures that lived alongside these Qikiqtania and other early tetrapods—the plants, invertebrates, and fish not lucky enough to be fossilized.

Still, Qikiqtania fossilized rather serendipitously amid the inescapable ravages of time. Stewart was amazed that Qikiqtania's fossil contained the fish's lateral line, a sensory system that helps fish sense flow around the body—the only early tetrapod fossil to have such scales preserved. "A fish like this would have had a thousand scales all over its body, and there are only a small, small, small fraction of those that have the features that tell us about the lateral lines," he said. "We were lucky to find them."