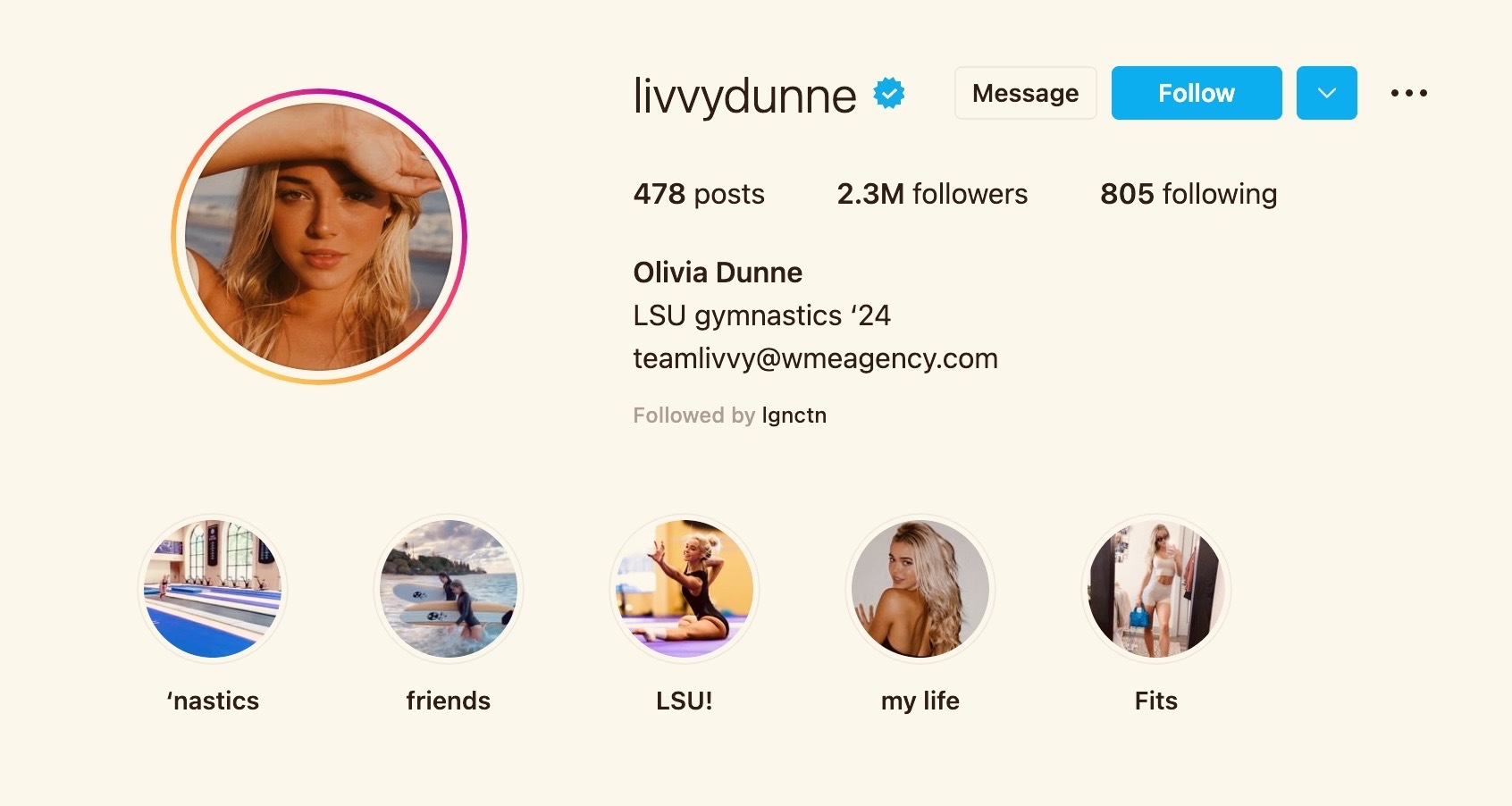

The New York Times published an article on Tuesday headlined “New Endorsements for College Athletes Resurface an Old Concern: Sex Sells.” The article centered on Olivia Dunne, a 20-year-old gymnast at Louisiana State University who, as the highest-earning female NCAA athlete in the country, has earned a reported $2.3 million in NIL deals, largely from advertising products on her social media accounts. On those popular pages, she posts photos that, as the Times put it, “[show] off [her body] in ways that emphasize traditional notions of female beauty.”

“Female college athletes are making millions thanks to their large social media followings,” the article’s subheading reads. “But some who have fought for equity in women’s sports worry that their brand building is regressive.” These resurfaced concerns from “some,” however, are ultimately attributed, rather vaguely, to just one person:

Stanford’s Tara VanDerveer, the most successful coach in women’s college basketball, sees the part of the N.I.L. revolution that focuses on beauty as regressive for female athletes. VanDerveer started coaching in 1978, a virtual eon before the popularization of the internet and social media, but she said the technology was upholding old sexist notions.

“I guess sometimes we have this swinging pendulum, where we maybe take two steps forward, and then we take a step back. We’re fighting for all the opportunities to compete, to play, to have resources, to have facilities, to have coaches, and all the things that go with Olympic-caliber athletics.”

“This is a step back,” she added.

It’s unclear from the story if VanDerveer was talking about Dunne specifically (though that didn’t stop the dumbest sports sites on Earth from writing about how a hateful hag and the woke NYT attacked a pretty young woman). The point VanDerveer is making is also unclear: Why would women’s sexual self-possession be at odds with equity in women’s sports? Cloudier still is why the Times would choose to pin an entire article’s premise on one criminally mixed metaphor from a 69-year-old who grew up in the '60s and '70s, when sex positivity was hotly contested. What seems clear is that the Times had a story it wanted to tell and was going to tell it: “The tension among body image, femininity and the drive to be taken seriously as athletes has been part of the deal for female athletes for generations,” the article asserts, with no supporting evidence. The drive to be taken seriously by who, exactly? Part of what deal? “Tension among?”

It’s worth noting here that the reporter on this story, a middle-aged man, does not include a single quote, not even a paraphrased one, from any current or former female athlete pointing out or even acknowledging this alleged tension. In fact, the only other athlete interviewed in the article, Stanford basketball player Haley Jones, who the Times attempts to cast as the chaste foil to Dunne’s implied provocativeness, emphasized that this supposed tension—to be “sexy” or not as a female college athlete—is, in the end, rendered moot by sheer, potent misogyny.

“You can go outside wearing sweatpants and a puffer jacket, and you’ll be sexualized,” Jones said. “I could be on a podcast, and it could just be my voice, and I’ll face the same thing. So, I think it will be there, no matter what you do or how you present yourself.”

Jones’s comment jibed with Dunne’s: “It’s just about showing as much or as little as you want.”

It seems like the real cause for concern here is not that female college athletes have difficulty understanding and navigating the terrain of being an athlete and a woman, but that the men who write about them do. In any case, of all the stories to write about how a class of exploited workers have just recently become free agents and are now exercising economic autonomy, and how this autonomy, while fraught and unequal, could nevertheless generate new solidarities and stimulate powerful desires in other workers, the Times chose to clutch their pearls over a 20-year-old posting bikini photos on Instagram and concern-troll about how it could harm women’s sports. The Times, lest you think it hadn’t thought about any of those interesting points and underlying systemic issues relating to how these NIL deals are distributed, made it known it had thought about it, at least just enough to include this perfunctory paragraph:

Race cannot be ignored as part of the dynamic. A majority of the most successful female moneymakers are white. Sexual orientation can’t be ignored, either. Few of the top earners openly identify as gay, and many post suggestive images of themselves that seem to cater to the male gaze.

A list of female college athletes with the highest NIL valuations does bear out this claim. An actual critique of NIL, then, should be this: So far, NIL has been a free-for-all, a rich, brand-new arena packed with boosters and companies and athletes and their agents racking up deals according to the market, which is to say on all the usual gendered and racialized terms. Workers getting paid is good. Racism and misogyny are still bad. What would a more equitable system look like? How could NIL lead there?

The potential for NIL to produce valuable answers to those questions is evidenced in the NCAA’s panicked reaction to a situation it chose to create and then immediately lost control over. Perhaps the NCAA was too arrogant and sclerotic to anticipate that NIL might lead to reinvigorated interest in a college football union, or the creation of NIL collectives that can do things like offer every player on a college football team a “base salary” and paid advertising opportunities to every student athlete at a specific university. These are the developments—which gesture towards NIL’s potential to foster greater solidarity, consciousness, and leverage among college athletes—that recently sent conference commissioners to the United States Senate, where they desperately pleaded for lawmakers to clamp some regulations on the NIL market. What clearer sign could there be that the NCAA’s grip on college sports has been significantly loosened by the introduction of something resembling an actual labor market?

Within this context, it’s hard to imagine an NIL case study less interesting or worthy of scrutiny than one built around Olivia Dunne, a person whose suddenly lucrative career as a brand spokesperson has far less to do with her identity as a student-athlete than it does with her newfound ability to participate in a well-established marketplace that was previously only kept from her by ridiculous regulations. It’s on this level that the Times story truly fails, in that any time spent hand-wringing over a woman making money on the internet the same way thousands and thousands of other women make money on the internet, for no other reason than the fact that this one happens to be a college gymnast, does nothing but serve powerful interests. The biggest favor anyone can do for the NCAA right now is to fret about the unregulated nature of the NIL market, to relocate coverage into the always fraught domains of sexuality and gender, and to conjure up ridiculous reasons to worry about equity in women’s sports. Don’t be surprised if at some point in the near future you see a Republican senator, who has never watched a single minute of women’s sports, arguing in favor of strict NIL regulations by waving around this Times article as evidence of the tremendous harm that NIL is doing to collegiate women’s sports. It wouldn’t be the first anti-NIL argument that revolved around specious concern for women athletes; initially critics assailed NIL on the grounds that only male athletes would benefit from it.

To return to the Times article’s silly thesis, the question should not be about whether female college athletes with NIL deals being “sexy” on Instagram will undermine the credibility of women’s sports. The interesting questions are about who is getting NIL deals and why, who feels threatened by them, and what could come next.