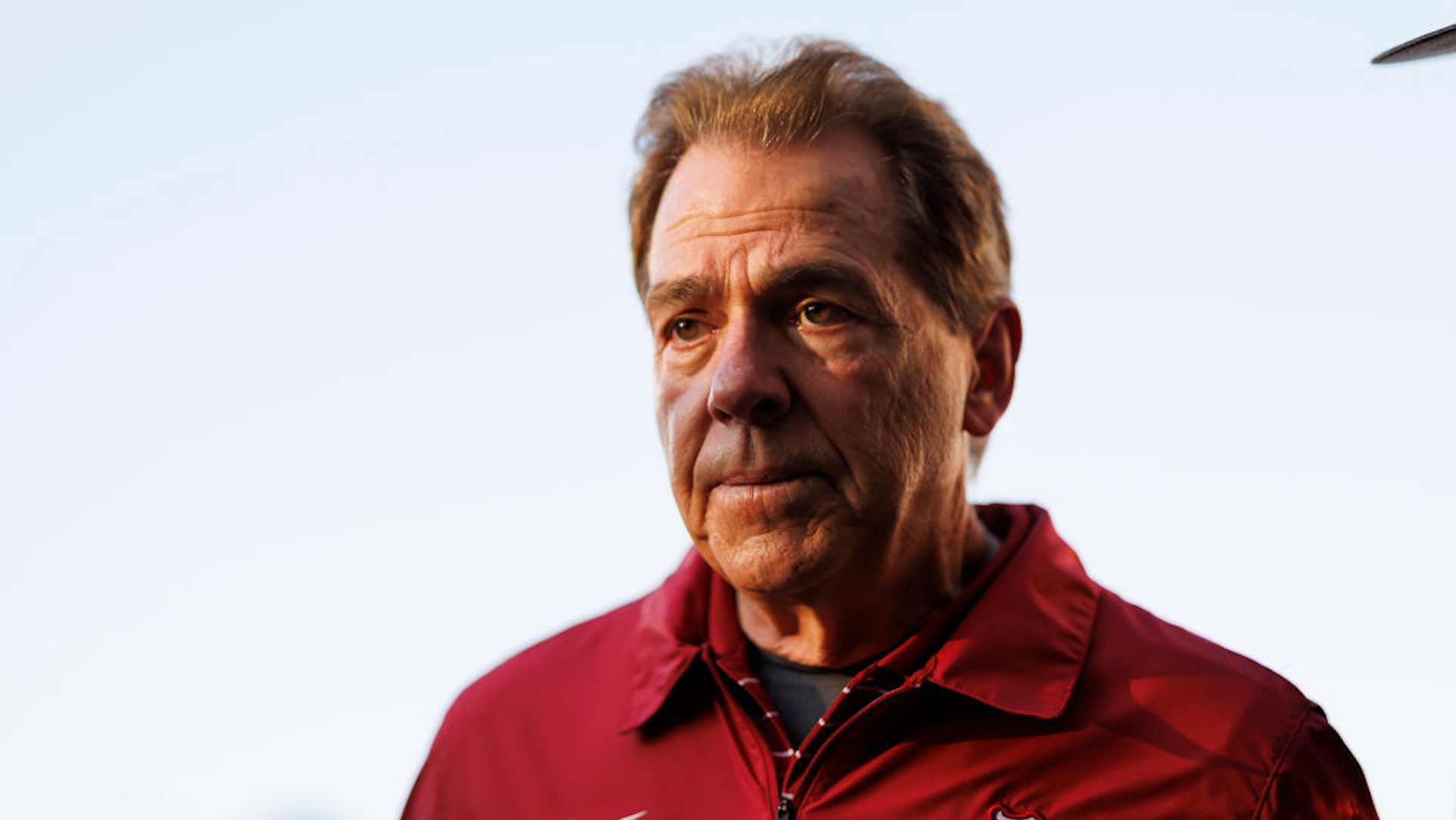

2023 will be remembered as Nick Saban's crowning achievement, at least by Nick Saban. This was the year when he did what almost none of his contemporaries have or will manage—leaving the gig on his own terms.

Saban announced his retirement as the head coach, athletic department head, and governor of Alabama on Wednesday, and for one of the rare times in the cutthroat business of cutting throats, that sentence requires no explanation. By all indications, he decided he had had enough of the mad life of the modern coach, told his bosses he was done, and walked out to the sound of his erstwhile superiors trying to talk him out of it.

That's a sound Pete Carroll didn't hear in Seattle. Bill Belichick didn't hear it in Foxborough. They'd also done more than enough for enough years to earn their own avenue out, but didn't get it because the hardest truth of coaching is that there are almost never any victory laps—just quiet, pitiable trudges out of the building and dropping the key card into the last wastebasket before the door to the car park.

Saban's legacy is revivifying and improving on the temple that is Alabama football. He leaves the building almost sure that his next few predecessors will not approach his achievements, that he will be missed even by the most irritating Crimson Tide fan (if that isn't a redundancy), and that he got to wake up yesterday saying the one sentence we all want to say and in almost no cases actually get to: You know, I don't have to do this any more, and I don't want to, either.

Most coaches will eventually be fired, even if it isn't called that in the release. There is always a careerist general manager or an impatient owner or, more trivial still, a regime change in which the new boss wants to show off to the mirror. Yesterday's parade doesn't feed today's need for public adulation—just ask any Golden State Warrior.

But Saban beat the reaper by doing three very rare things. The first is repeating and then improving on the finest of one's predecessors by winning bigger trophies more often and generating so much money that the company will live off the interest for decades. The second is to grow so old in the job—minimum age 70—that firing seems more cruel than therapeutic. And the third, the harder part, is sensing the moment when it will never be this good ever again, and being OK with the possibility that even while you're sitting on the boat fiendishly merging pinas and coladas, you might actually be wrong.

This seems obvious, but the thing about our culture that arches over everything and everyone is that we hate old people, at least a bit. No coach who has ever reached his or her 70th birthday in the job has not heard the plaintive and empathetic cry, Why don't you quit, you withered, drooling, liver-spotted old bastard? Belichick's two fists of power rings did not protect him from scorn, and neither did Carroll's chirpy good-cop-hall-monitor optimism. Even Gregg Popovich, who may be the most bulletproof coach of them all, is always one cranky mood by his boss from getting dragged along the Riverwalk, and yes, he knows it as well as anyone even after 28 years.

So here's to Nick Saban, who can now tell all his friends and anyone else who will listen that the last thing he did at work was set fire to his personnel file and laughing uncontrollably while making a wanking motion at the entire board of trustees. There is no greater victory in this or any other world.