In 2011, near the Bavarian village of Wattendorf, scientists excavating a slab of limestone studded with the bones of early crocodiles were surprised to find a fossil of a pterosaur. Although the stone was broken in 17 pieces, the skeleton was almost complete, with viable joints and ligaments, according to a description of the fossil published the journal Paläontologische Zeitschrift, or PalZ. But the real wonder was the pterosaur's extraordinarily long jaws, flared and flat at the tip like a hoe and fringed with at least 480 teeth—which implies there may be even more teeth, given the poor preservation of teeth in one region of the fossilized jaw.

This new pterosaur, which is not a dinosaur but lived among them, has been named Balaenognathus maeuseri, after the bowhead whale, as both have similar filter feeding styles. But unlike B. maeuseri, bowhead whales do not have teeth. Instead, they have baleen—bristly plates made of keratin that can strain plankton from the sea. The researchers hypothesize the new pterosaur would have waded into shallow lagoons, funneled water into its mouth using its spatula-shaped beak, and then squeezed out the liquid, filtering out plankton with its fence of "fine, slender" teeth.

I am not saying this style of filter feeding, or even the immensely dense fence of teeth, is weird. Filter feeding itself isn't particularly rare; clams, sponges, and fishes do it, often without the help of any teeth. The northern shoveler has more than 100 tooth-like projections in its bill that help it dabble in the water for food.

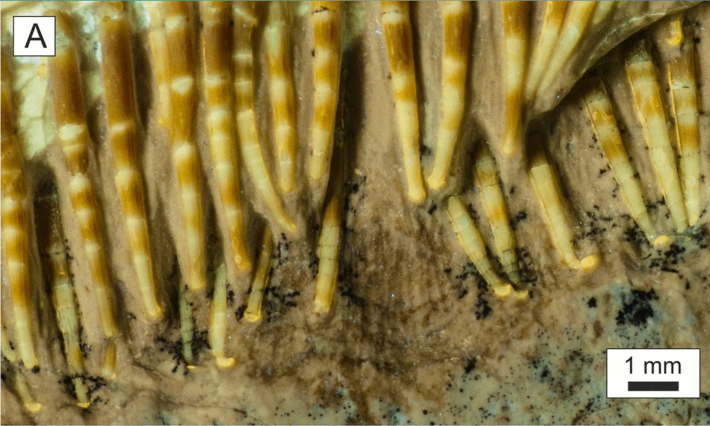

In my opinion, the truly strange thing about the new pterosaur's teeth are a series of "nubbins and hooklets at the tip of the tooth crowns." Nubbins and hooklets, you say? Now we're talking. I have never heard "nubbin" nor "hooklet" applied to teeth, and the mere apposition of such terms had me hooked. Instead of tapering to a needle-like point, the new pterosaur's teeth terminated in these hooklets (small hooks) and nubbins (small lumps). These knobbly ends prevented the interdigitation, or interlocking, of the pterosaur's teeth, meaning the creature would not have been able to fully close its jaws. The hooklets, at least, appear to have a point; they could catch the tiny shrimp the pterosaurs ate, one of the researchers suggested in a press release. The nubbins? Less clear. I respect a truly enigmatic set of chompers.

There is one other species of pterosaur with more teeth than B. maeuseri. By the lakes of what is now Argentina, Pterodaustro had a mouth of about 1,000 teeth, with short and stubby teeth in its upper bill and long, needle-like teeth in its lower bill. This is also an impressive set of teeth, tragically lost to the past along with Helicoprion's baffling toothy pizza-cutter jaw.

No shade to the human mouth and our austere set of 32 teeth, but a mouth with 1,000 teeth was surely a thing to behold. All this tooth talk reminded me of a paper published earlier this month in Nature, which found a decline in "disruptive" science, meaning papers that push a field in a new direction. Where are the groundbreaking teeth and singular jaws of this century? Is the Golden Age of Teeth behind us?

Modern earth is not entirely without innovators. The crab-eater seal, which looks like a living squishmallow from the outside, boasts some intricately cusped teeth that look like ossified flame emojis. These teeth help the crab-eater seal, which—psych!—eats nary a crab, sieve krill from seawater. The frilled shark has around 300 backward-facing, pronged teeth, which some find to be grotesque but I find to be innovative; apparently, they help the frilled shark lure and snag squid. And who is more iconic than the spiraling tunnel of teeth that help the lamprey latch on and suck? It is an honor to exist alongside teeth like these. It's no wonder the frilled shark and lamprey are considered primitive vertebrates—remnants of a past era when dentition could get truly disruptive.