The moment at which an astute but otherwise objective observer might have begun getting suspicious about whether something might be going on with the New York Mets would probably have been late June. This was when it came out that the team had adopted as a clubhouse anthem the song that a reserve infielder had recorded in his home studio about being grateful and having a nice time. I can only guess at that perspective in this case, but take your own fan investments out of it and run this exercise through yourself.

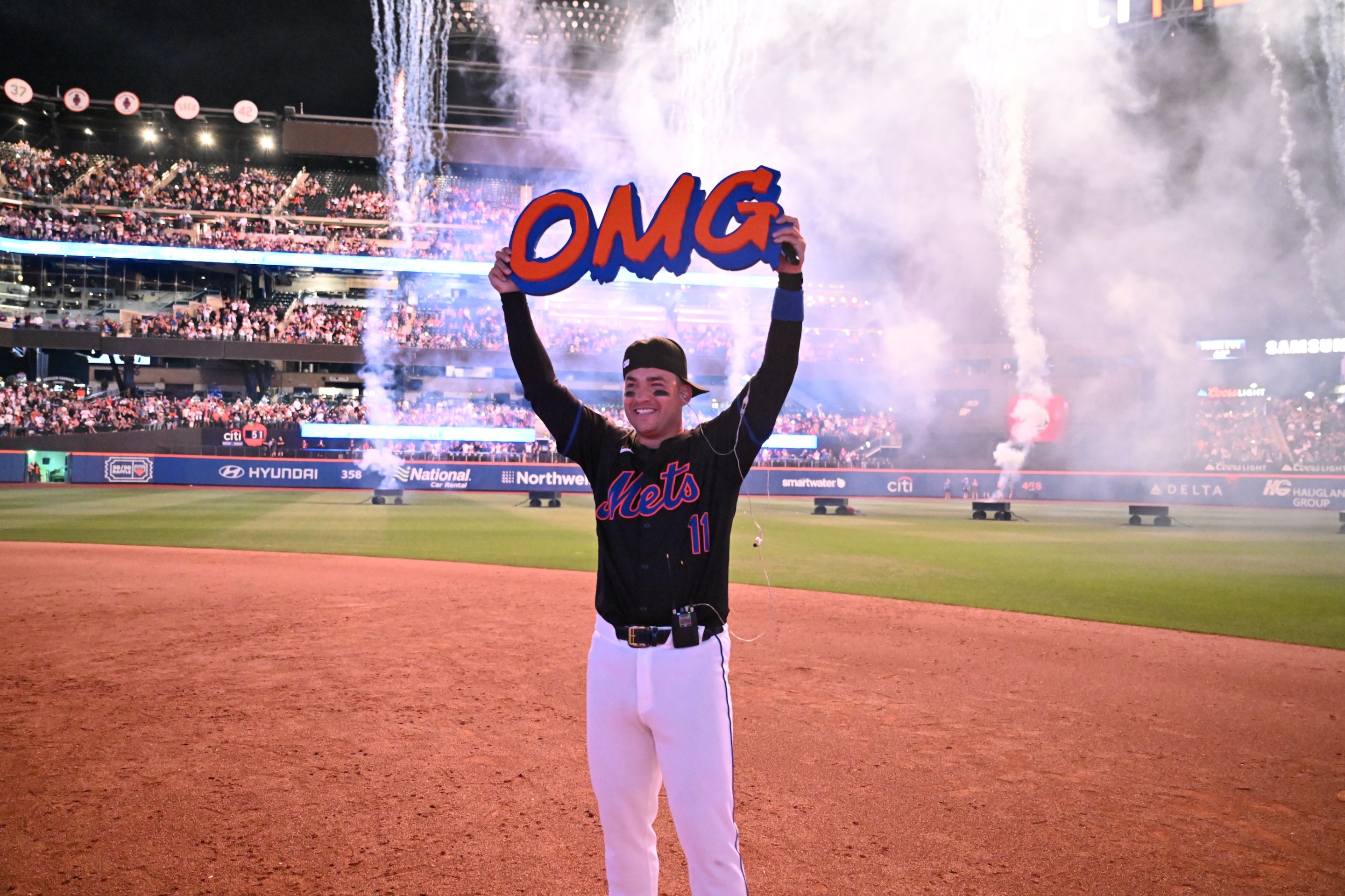

If you learned that, after wins, the baseball team you cared about was shouting along to the chorus of a song that the resident thirtysomething utility spork had recorded in his spare time—it could be Kevin Newman or Donovan Solano or whoever you like, in whatever genre you find most amusing to imagine—there would be in that news the sense that the good kind of weird thing was happening in that clubhouse. Any team that signed Jose Iglesias to a minor league deal, installed him as an everyday player out of necessity and watched him have the best season of his career at the age of 34, adopted his song, and then won nearly two out of every three games for four months would have some sense of destiny about it. It's simply too stupid not to mean something. The challenge has been believing that this could happen, and then accepting that it was indeed happening, to the New York Mets.

The Mets' win over the Phillies in Game 1 of their National League Divisional Series on Saturday was, in contrast to the team's other big wins of the last week, a pretty normal type of baseball game. The wildness of those other Mets wins—the wild last two innings of the team's postseason-clinching victory in Atlanta happened last Monday, and Pete Alonso's Wild Card-winning ninth-inning homer off Devin Williams was on Thursday—makes that a fairly meaningless standard, but also created a unique sort of context. That the Mets were utterly overmatched by Zack Wheeler over seven innings before breaking through against the Phillies bullpen in what wound up being a 6-2 win was not notable in itself; it is just about the only way to beat the Phillies on the days when Wheeler starts, and the depth and excellence of Philadelphia's bullpen makes it very difficult to do. But the fact that the Mets had staged two once-per-decade comeback wins in the last five days cast the late cavalcade of stubborn at-bats and eighth-inning singles in a different light. It was not inevitable, because the Mets are not that kind of team. But it felt reasonable in a way that it patently was not. Every ball that slipped or snuck or slunk through a hole in the infield had an of course tailing behind it. How that phrase sounded depended upon which team you were cheering for.

If you have watched enough baseball, you have seen a team that wins like this; it is likelier that you have been victimized by such a team than cheered for one. There are teams that enter the postseason as favorites and end it as champions seemingly without breaking a sweat in the process, but it's the nature of the playoffs—and especially of the new format, with its sprinted-through series between exhausted teams—to bring teams like that low. There is enough room for stupid things to happen, but not enough time for all that chaos and chance to even out in the ways it does over a regular season. It's not just that teams get lucky, although that's an inextricable part of it. It's more that everything is steepened and condensed in a way that makes it possible for a team to forget itself so fully that it effectively becomes something else. The last World Series was played between two teams like that; neither one of them made the postseason this year.

It works until it stops working, but the teams that get it working are not recognizably themselves. I think of the Colorado Rockies streaking from the middle of their division all the way to the World Series in 2007, but you might have a different one in mind. Those Rockies awakened at the worst moment, and got swept by a much more reasonable-seeming champion. In 2015, the Mets and the Royals both reached the World Series as that kind of team; it was possible to believe any preposterous thing about either of them when the series started, but as one Royals grounder after another skipped right where it needed to go and one increasingly audacious gamble after another paid off it became clear which one had it and which one didn't. For a fan on the wrong side, the feeling was something like waking up in a room that you don't yet realize is your own; for a fan on the right side, it seemed reasonable that this team could win each of the next five World Series. That's not the way it works, but that feels like and in point of fact really is a silly thing to think about while it's working.

The rest of this baseball season will, among other things, be about seeing how or when or if this holy fog burns off. There are a number of teams that seem to have it. The Mets, their threadbare bullpen and luridly in-between starting rotation and pothole-strewn lineup notwithstanding, have it. This year's Tigers have this kind of thing about them, too; so, Saturday's flubby clunker of a Game 1 loss against the Dodgers notwithstanding, do the San Diego Padres. That the Padres have more good players than, say, the Tigers or the Mets is a good reason why they seem likelier to win the World Series than either team, but it doesn't feel convincingly decisive. Every year around this time, for very good teams, it isn't.

The caveats effectively present themselves: there are middling teams that sincerely love playing together; every team has some sort of lite choreo they do after hits and most have some goofy home run totem or prop, and those dim memes only seem to mean anything when the baseball stuff is also working; for all I know Garrett Hampson has a lovely singing voice and every locker room has a potential hitmaker in it. This thing only really works in this irrational and manic stretch of the season, and it only sort of works even then. It doesn't really override all the more reasonable and readily quantifiable stuff; the thrill of it is that it feels like it could, and the fun of October is that, in these short and stupid little series, it actually can. A team has to be pretty good to make it to October, but the ones that are lit up like this—the teams that seem too happy or too goofy or too distracted by their own silly in-house bits to remember the stakes—have an advantage for that. To play like you're dreaming, to be that far outside and above the moment, is by its very nature not sustainable, and certainly not something that outweighs stuff like "having more good players"—it's not something anyone can really prove exists, although I don't know any fan who doesn't believe in it. You'd much rather have it than not.