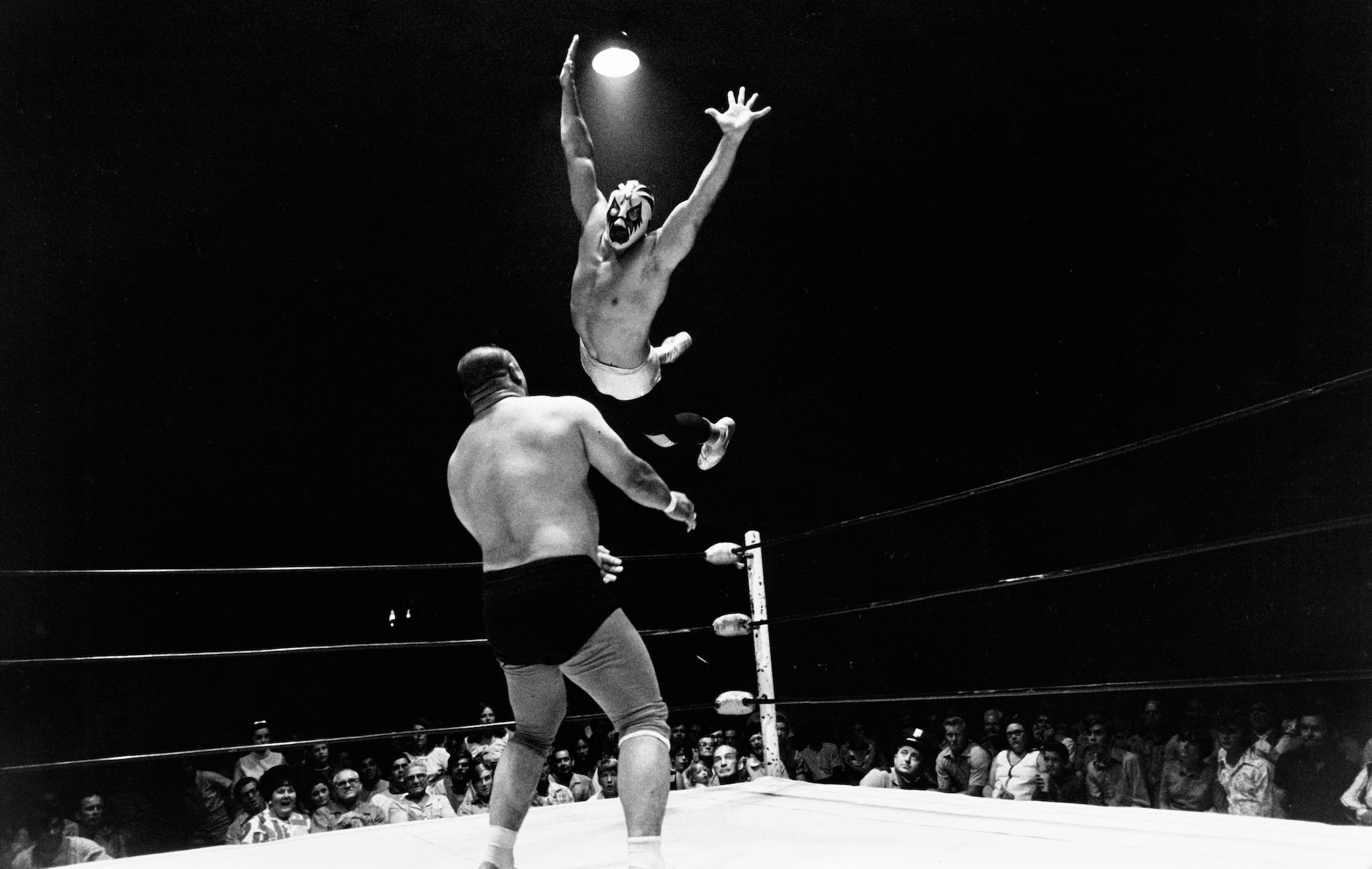

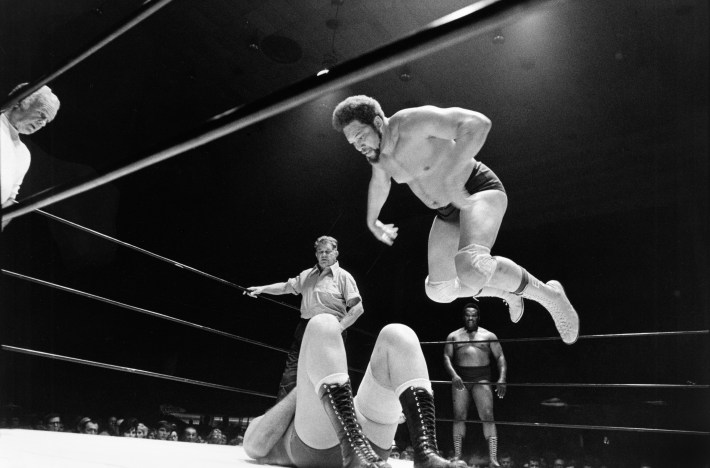

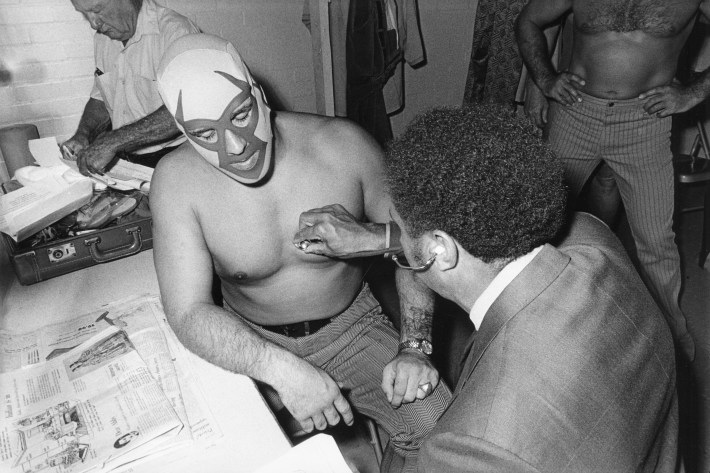

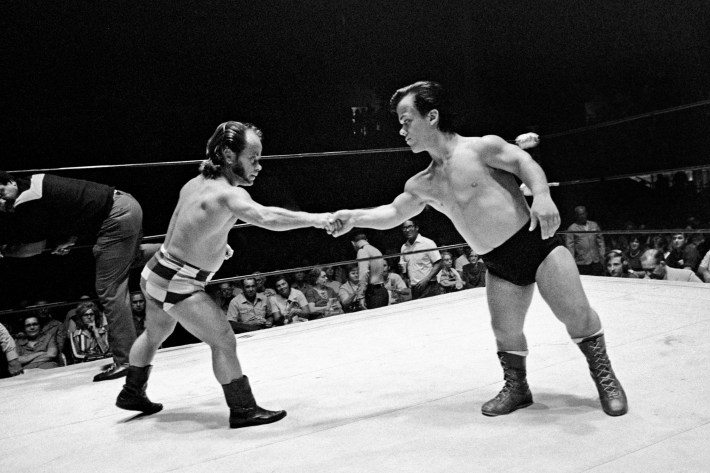

When photographer Geoff Winningham walked into the Houston Coliseum on a February evening in 1971, he unexpectedly discovered his muse: professional wrestling in its freewheeling and grassroots glory, with thousands of rabid spectators cheering for the likes of Mil Máscaras beneath his lucha libre mask as he leapt from the ringpost, and booing the likes of Ernie Ladd, the imposing refugee from the NFL, as he hammered his hapless opponent into submission.

Winningham embedded himself in the arena for the next eight months to document the mayhem and the drama. In a fervid rush he published a book at the end of the year: Friday Night in the Coliseum, featuring over 135 photographs interspersed with interviews he conducted with the wrestlers, their families, and the ringside faithful.

Friday Night won Winningham national acclaim, but his haste and inexperience resulted in numerous glitches in the book. Over the years, he lamented that the first edition didn’t meet his expectations, that its production didn’t match the quality of the photographs. Last year, as the 50th anniversary of Friday Night approached, he decided to self-publish a new version that would reveal the true essence of the Bayou City’s bygone wrestling scene.

“The original book doesn’t look good now,” he said. “I wanted a printing that looked as good as I could make it.”

Winningham first arrived in Houston from Jackson, Tenn., in 1961 to attend Rice University. He took photographs for the yearbook, but was intent on going to Vanderbilt law school after graduation. But with prodding from several professors, he deferred his admission and went to Chicago to study photography at the Institute of Design. There his teachers included some of the most revered names in modern photography: Arthur Siegel, Aaron Siskind, Harry Callahan, Wynn Bullock. But Winningham found their aesthetic of visual experimentation and artistry unappealing. Instead, he venerated the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, he of the “decisive moment,” which was both the title of his groundbreaking monograph and a description of his philosophy. (The person who sold Winningham a used copy of The Decisive Moment was none other than novelist Larry McMurtry of Lonesome Dove fame, who was a visiting lecturer at Rice and worked at a bookstore.)

“When I saw The Decisive Moment, it just swept me away,” Winningham said. “It was so rich in its humanity, so beautiful in its visual pleasure. I thought to myself, ‘My god, could I possibly do something like that?’”

Winningham’s second major influence came from Weegee, real name Arthur Fellig, the New York photojournalist who prowled the streets of the Naked City with his trusty 4x5 Speed Graphic camera in search of something, anything, dramatic: accidents and gangland slayings, celebrities and the demimonde. “Weegee once said something like, ‘A good photograph should be like a blintz. You want to eat it while it’s hot,’” Winningham recalled.

“That was my thing: Don’t give me art. Give me something real,” he continued. “I didn’t want to be seen as an artist. I wanted to be seen as a photographer. I didn’t want to make photographs that were poetically resonant. I wanted to make photographs of the real world.”

When he returned to Texas in 1969 to teach photography, first at the University of St. Thomas and then at Rice, Winningham was determined to become “the Weegee of Houston.” So he started going to parades, concerts, political rallies, rodeos, sporting events, art openings, wrestling shows—anywhere that attracted crowds, because “that’s where I might find my next picture.”

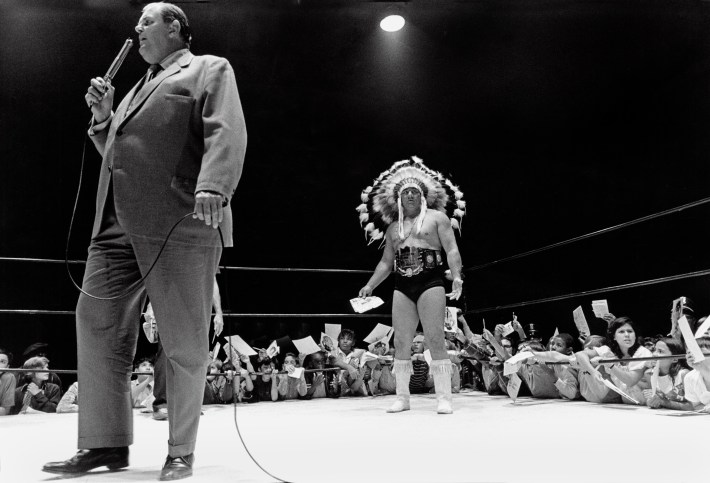

In the winter of 1971, Winningham saw a notice in the Houston Post for an evening of professional wrestling at the Coliseum, with Wahoo McDaniel (a veteran NFL player) and Johnny Valentine clashing in the main event. The Friday night cards were ignored by the sports journalists in town who were more concerned with Houston’s newly minted status as a major-league sports hub, what with the Oilers, born in 1960 in the AFL; the Astros (formerly the Colt .45s), who started in 1962; the debut of the Astrodome, the “Eighth Wonder of the World,” in 1965; Elvin Hayes’s NCAA run with the University of Houston Cougars; the NBA’s Rockets (who came from San Diego in 1971); and, soon enough, the Aeros of the short-lived WHA.

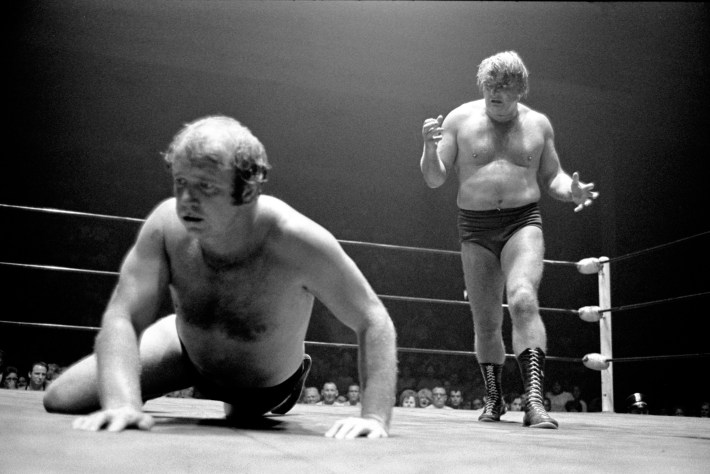

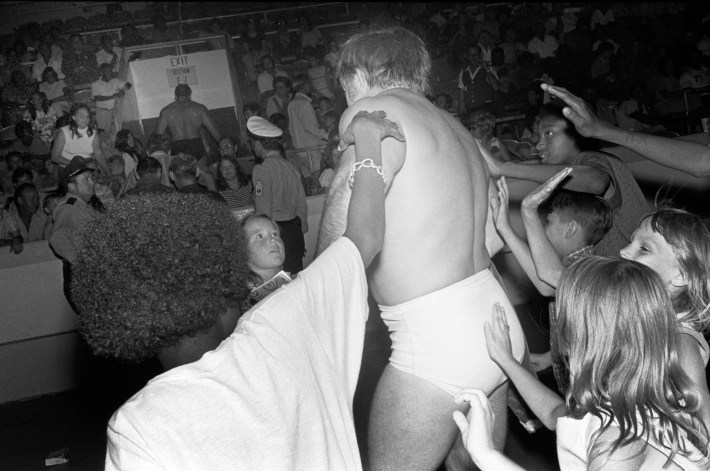

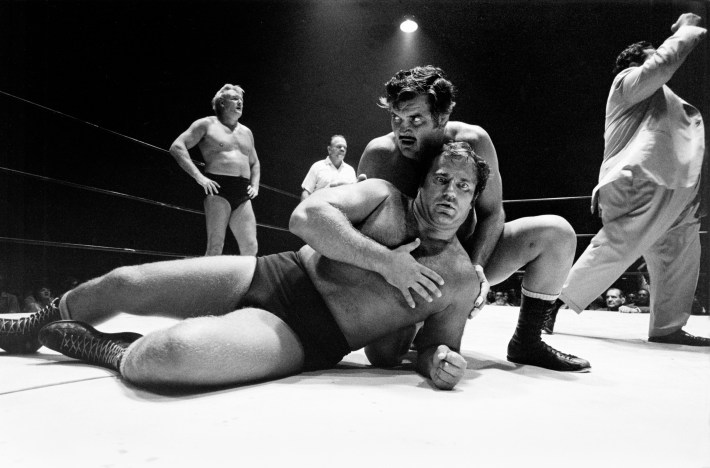

Professional wrestling thrived as a regional niche in strongholds like the Coliseum. There, passionate fans gathered to cheer and heckle behemoths like Killer Kowalski, “Classy” Freddie Blassie, Dory Funk Jr., Antonino Rocca, Pedro Morales, Andre the Giant, Gorgeous George Jr., and Bruno Sammartino. Villainous Nazis bounded into the ring dressed in knee-high leather boots and monocles; Asian “heels” paraded in kimonos, wooden sandals, and Rising Sun headbands. Not to mention the occasional battle royal, cage match, female grapplers, and tag-team “midget wrestling” with Cowboy Lang, Little Tokyo, and Lord Clayton Littlebrook. The blood was real, as was the brutal grace of the performers in what philosopher Roland Barthes once described as “a spectacle of excess.”

The Sam Houston Coliseum and Music Hall were built near downtown during the Great Depression. The WPA-funded facility hosted rodeos, conventions, circuses, and big musical acts from Elvis Presley to The Beatles to Jimi Hendrix. The night before he was assassinated in Dallas, President John F. Kennedy attended a dinner at the Coliseum to honor U.S. Representative Albert Thomas’s effort to bring NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center to the Houston area.

But by the early 1970s, the aging venue clashed with the city’s space-age image. The annual Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo packed up and moved to the Astrodome, and when Elvis returned to Houston in 1970 he too played the Dome. In 1971, when the Rockets arrived and awaited construction of The Summit, they refused to play their home games at the Coliseum. Still, it was perfect for wrestling.

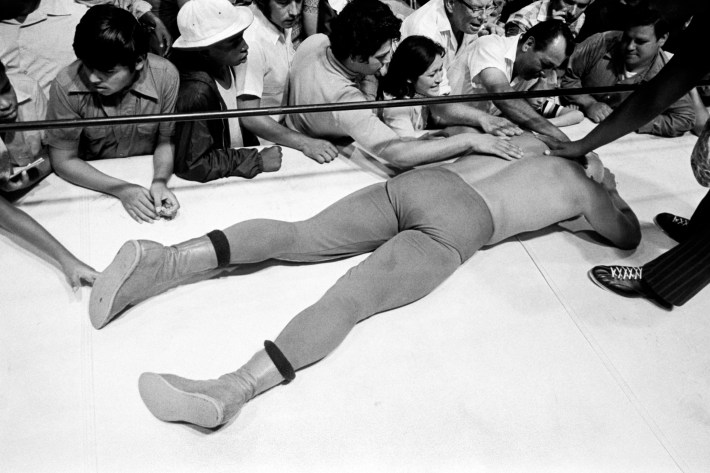

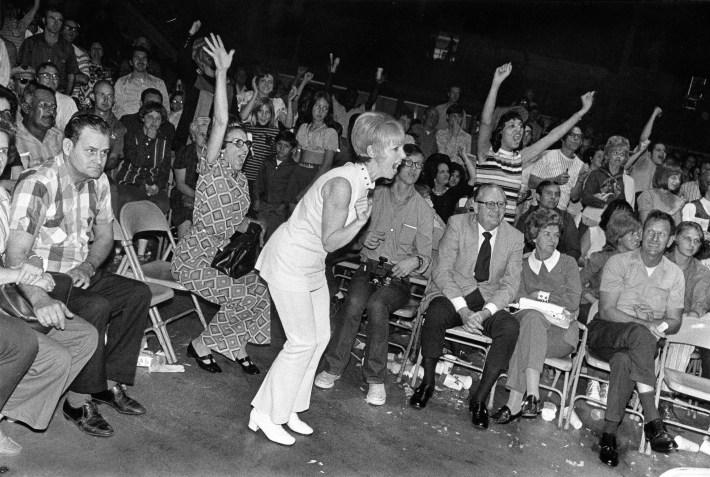

Winningham later recalled his first impression of the scene: “The bright lights, bearing down on the white mat over the roped ring in the center of the Coliseum. The place was packed, a sellout crowd of over 7,000 people, screaming, shouting. No one even noticed me. I went right to the edge of the ring, looking up at the action, where very large men, nearly naked, their bodies glistening with sweat, were flying through the air at each other, then gripped together in tortuous holds, almost too painful to watch.”

Thanks to the benevolence of promoter Paul Boesch, Winningham enjoyed unlimited access in the Coliseum. He didn’t care which wrestler won or which one lost, or even whether the matches were fixed. He slung three Leica M6 cameras around his neck, each equipped with a different lens, and brought along a Sony tape recorder. As the smell of fresh popcorn wafted in the air, he snapped 186 rolls of film and interviewed scores of spectators in their blue jeans, bouffants, and pompadours.

Winningham transcribed the conversations and developed the film in the darkroom. When he felt he had enough material for a book, he laid out a rough cut. He took as his immediate inspiration a recently published book by Roger Minick, entitled Delta West: The Land and People of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, whose photos were accompanied by the words of the subjects he photographed.

The interviews Winningham conducted highlighted the intimate connection between the crowd and the athletes inside the Coliseum. “One time Johnny Valentine jumped down in front of me and I got up and shook my finger in his face and I said, ‘You are so mean, your mother don't even love you,’” a female fan told Winningham. “And he drew back his hand like he was goin’ to slap me and my husband said, ‘You hit her and I'll find out how much money you have.’ I love it. I mean there is nothing else I love better.”

“What I really love most is the vernacular,” Winningham said. “Pictures are good enough, but the words with the pictures are what I want.”

That fall, he contacted Jess Allison, a local salesman in the printing business who admired his pictures. Allison agreed to put up $10,000 to cover the production costs. Houston-based Wetmore and Co. printed 10,000 copies, but when the book went to the bindery, disaster struck. Some 8,500 books were ruined and had to be destroyed.

That turned into a blessing in disguise, according to Winningham, because Friday Night didn’t fly off the shelves. “Those 1,500 copies took us about 10 years to sell,” he said. The following year, he shot a 16mm documentary about wrestling in the Coliseum, funded by the public broadcasting TV station in Austin, but the film was rejected and never aired.

Even so, the book brought him considerable attention. A.D. Coleman, a pioneering critic as photography was evolving into a legitimate creative medium, both in documentary form (including journalism) and synthetic (or manipulated) work, wrote in the Village Voice that Winningham’s portrayal of this “fascinating subculture ... succeeds marvelously. I haven’t had as much sheer, uncomplicated, unmitigated fun with a book for a long time. ... Certainly one of Winningham’s accomplishments with this book has been leaving himself open to experience fully something which a great many people sneer at and deride, and because he did so this book serves, in a very humanizing and loving way, as a bridge for anyone else open enough to cross it.”

The New York Times followed with a rave review (“a masterly exposition”), and Winningham’s photos were featured in Newsweek, Atlantic Monthly, and Life magazines. His work also appeared alongside pictures by Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, and Tod Papageorge in Mirrors and Windows: American Photography Since 1960, a book edited by John Szarkowski, the influential curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

The praise gave him newfound confidence to follow his instincts. He followed Friday Night with Going Texan (1972), about the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo at the Astrodome (with an essay by Rice University sociology professor William Martin). Then came Rites of Fall (1979), an homage to the civil religion of high-school football in the Lone Star State; this was Buzz Bissinger’s Friday Night Lights brought to life via stark photographs taken from 1972 to 1978. Text by legendary journalist Al Reinert, who was nominated for an Academy Award for his Apollo 13 screenplay, stitched together the images, concluding with an essay by Dallas Cowboys quarterback and TV commentator Don Meredith.

“I’ve watched the movie [Friday Night Lights] a dozen times at least,” Winningham said. “I love the movie. Parts of it bring me to tears: the yearning, the need, the passion. Those kids are performing for their town, their people, to the world.”

Some 50 years later, Winningham revisited Friday Night in the Coliseum. He’d long bemoaned the flaws, big and small, in the first edition. Typos abounded, and the copyright notice was in the wrong place. When he reviewed the original proof sheets, he found photos that he’d missed in his eagerness to publish the book. Worse, the interior spot-varnish applications on the photos, which give the images a subtle sheen and make them “pop” from the page, did not age well.

Winningham created a new, state-of-the-art version by digitally rescanning the original negatives of the photographs that appeared in the book, along with about a hundred others that were not included in the first one. He used Adobe InDesign to construct the layout; corrected typos and re-edited the text; eliminated photos that he felt “no longer worked”; added 41 images and an afterword; used tritone (three different inks) separations; and expanded the book by nearly 40 pages. Some 500 copies of the second edition were printed by Everbest Printing Company in Hong Kong; Winningham himself handles sales and shipping through his website.

“Publishing a book now is a whole different thing with the internet,” he said. “In the past you could do a book on your own and privately publish it, but then you couldn’t distribute it. So, you were left with a lot of books. Nowadays, with a little bit of effort, you can reach people yourself.”

The second edition is well worth the wait. The visual dynamics on the page match the vibrant scene inside the Coliseum: The vintage photographs crackle with the oomph of a Mil Máscaras dropkick, and the fresh images surprise and delight. It feels as if we’re sitting ringside alongside Winningham, watching as a succession of burly wrestlers ooze sweat and gush blood and a motley crew of spectators alternately cajoles and berates their performances.

Long before the WWF-ification of professional wrestling, and long before the disparate regional scenes were consolidated into a national empire built upon Technicolor glitz, steroid-enhanced beefcake, TV dollars, and WrestleMania, Friday Night serves as a time-capsule tribute to what Winningham describes as “the greatest folk theater on earth.”

Paul Boesch ended his long-running wrestling shows at the Coliseum in 1987, and the obsolescent arena was demolished in 1998. Its local legacy lives on in the age of Spandex: In 2001, nearly 70,000 fans flocked to the Houston Astrodome for WrestleMania X-Seven, while millions more watched on pay-per-view.

Winningham, 78, still teaches photography at Rice; he is currently the Lynette S. Autrey Professor of Humanities and a professor of visual arts. He and his wife, artist Janice Freeman, split their time between Houston and a home they built in Mineral de Pozos, Mexico. During the pandemic, he’s been putting together his next book: a collection of color photographs about the Day of the Dead, gleaned from his experience documenting the rituals throughout Mexico over the past 35 years.

“I’m in my third year of playing around with the layout,” he said. “I hope to maybe get it out this year, if I can get the text right. The one thing I’ve learned, when it comes to doing a book, is that I need to give it lots of time because even though I think I may have it finished, if I set it aside for six months and come back to it, I will make it better.”

As good as a hot blintz.