The Cincinnati Bengals beat the New York Jets last weekend. I didn’t give a rip about the game, but it got me missing Boudreaux all over again.

Boudreaux was a sports radio supernova in D.C. in the mid-1990s. In all my years of typing, I’ve never met anybody who made me laugh as much or scared me more. He was the consummate anti-fan. I was in awe of his rants ripping the Washington Football Team, which were delivered in a coarse Southern drawl and came at a time when the local media’s coverage of the most popular and most valuable sports franchise in the market was Charmin soft.

He tore down institutions, too. I remember falling hard for Boudreaux when he torched historically untouchable Hall of Famer and former WFT quarterback, Sonny Jurgensen, the most beloved athlete in the history of the Nation’s Capital. “Sonny Jurgensen has gotten more mileage out of an empty tank than Amelia Earhart,” Boudreaux once railed. “Know this about Sonny Jurgensen: The guy never lost a beer gut and never won a playoff game.” Stats support this Sonny-centric sacrilege.

Boudreaux was already the star of WFT postgame radio shows—I remember WJFK-FM host and former Washington center Jeff Bostic whining “Boudreaux, my man, where are you?” on a rare week when he didn’t call in—before I ever met him. Our relationship changed in late 1995 when I heard “Boudreaux from Northern Virginia” call into a national show syndicated by One On One broadcasting, a now-deceased Chicago-based talk radio network.

Boudreaux had delivered a long poem he’d written about O.J. Simpson’s trial that ended with a line about the low-speed chase in the white Ford Bronco: “Death rides a pale horse!” At the time, I had a weekly column in Washington City Paper, an alternative weekly. I called the show’s host, John Renshaw, and asked him to broker a summit. Boudreaux only agreed to be interviewed if I didn’t ask questions about his personal or professional lives, and he refused to let us photograph him. I didn’t even know what his real name was and agreed not to ask that, either. I just wanted to meet the guy.

I’m so glad I did. I ended up writing at least 14 stories about Boudreaux for Washington City Paper through the years. Most were just transcriptions of his WFT rants. (Interested parties may read them here.) Sports talk tends to be period specific. But some of Boudreaux's takes transcend time and turnover. Like his summer of 1999 prediction for Dan Snyder, whose takeover of the Washington franchise, based on all the reporting from D.C. media on the boy-wonder owner, meant winning ways were imminent. Snyder's first free-agent targets at the time included Deion Sanders and Barry Sanders. “I have a feeling this Snyder kid might be in over his head," Boudreaux said. "My guess is young Daniel will look like Col. Sanders before he wins a Super Bowl.”

I loved talking to him off-air. He was a complete weirdo and as paranoid as the day is long. But, man, he made me laugh.

The lack of checkable background information in my Boudreaux stories caused my editor, David Carr, to half-jokingly question whether Boudreaux actually existed. I told him I wish I could come up with lines as sharp or witty. But Carr kept voicing his suspicions that all the WFT bashing material really came from an alter ego of mine until a photographer for the paper, D.C. icon and 35mm genius Darrow Montgomery, vouched for his existence after accompanying me and Boudreaux to a disastrous interview with Johnny Unitas.

Boudreaux had told me many times that the Baltimore Colts legend was his childhood hero. To try to pay him back for all the time and laughs he’d given me for my columns, when I was offered a chance to interview Unitas at a D.C. hotel in November 1996, I brought Boudreaux along with me. Yes, I knew how unprofessional bringing a fanboy to an interview was. But Boudreaux was an encyclopedia on Johnny U., and I figured Unitas, for all his sporting brilliance, would be boring as hell anyway.

It didn’t go well. I realized I’d made a massive mistake when I met Boudreaux outside the hotel before convening with Unitas. He looked like a central casting version of a hardscrabble reporter, wearing a fedora with a pencil propped on his ear and carrying a big yellow legal pad with tons of scribbling on it. I begged him to just sit and listen during our audience with the guy who was named the greatest player of the NFL’s first half-century, and Boudreaux said he’d behave. Unitas was even blander than I’d feared, and constantly avoided talking about his own gridiron greatness to instead focus on prostate health awareness, which was why he was offering interviews.

I had given up getting anything interesting out of him when Boudreaux broke his vow of silence and launched into a breathless, ridiculously long recollection of being in the L.A. Coliseum for the 1962 NFL Pro Bowl. He was still going miles a minute when he got to the part about seeing Unitas scramble around on the game’s last snap and find Jon Arnett of the L.A. Rams kneeling in the end zone, and hitting him for the game-winning score as the sun was setting. “How the hell did you do that, Johnny?” Boudreaux shrieked. I was steaming about Boudreaux’s betrayal at first, but pretty quick it became obvious I was in the presence of greatness—and not just Unitas’s.

Unitas actually took the time to say he did in fact remember that Pro Bowl–winning throw and add some details. But before the alleged greatest player in NFL history could say his piece, Boudreaux launched into another adolescent memory of Johnny U.’s derring do, at which point the transcendent QB visibly shrugged. The prostate awareness flack who arranged the interviews, a guy memorably named Tom Jones, hustled over to save Unitas. Jones asked us to leave, but didn’t trust that we’d go quietly. “I'll walk you guys out,” Jones told us. “It's really hard to find the exits in this hotel."

I gave Boudreaux a what-the-hell-were-you-thinking look when the bum-rush ended and Jones left us standing on a sidewalk outside the hotel.

“I’m sorry, David. I really thought I was doing good,” he said earnestly. Then his mood changed.

“Fuck Johnny Unitas,” he snapped.

And we both broke out giggling like schoolchildren.

Unitas wasn’t the only guy Boudreaux turned on. He stopped calling sports talk stations because he thought the D.C. media served as a "marketing arm" of the WFT operation and figured his radio appearances, negative as they were to the team, were still only feeding the beast. And he would go underground on me for years at a time after perceiving various disloyalties. I didn't know his phone number because he always called me from pay phones or businesses or phones borrowed from strangers. After one such hiatus he called up and accused me of trying to find personal information out about him that in his head I would somehow use to get him in trouble, and insinuated harm would come my way if I didn’t abide. I told him I’d stick to my pledge, and he agreed to not disappear on me again.

But that pact didn’t last forever. By late 2020, I hadn’t heard from Boudreaux in at least six years. The pandemic body count was rising and I got to worrying that he’d been a COVID statistic. I called up a gym in Northern Virginia that I knew he’d frequented back in the day, and described a disheveled raconteur old guy who called himself “Boudreaux” who to me seemed blatantly unforgettable. The gym owner immediately knew who I was talking about. And he gave me his real name, which didn’t have “Boudreaux” either first or last. I’d just started thinking how mad Boudreaux was going to be at me just for making that phone call when I learned that wouldn’t be an issue.

“He died,” the owner told me.

He said Boudreaux had been dead for a while when his body was found in late 2019 at his house. The owner said a sibling lived locally and said a fall was suspected. I checked with a local courthouse and found out the official cause of death was “blunt force trauma to the head and neck,” which was ruled “accidental.” He was 76.

I was shocked by the news and really sad that I’d never again guffaw with or get yelled at by Boudreaux. I knew this was a special guy, somebody who deserved more notoriety than whatever sports radio calls and a few columns in a weekly newspaper brought him. I was sad as hell he died alone, and selfishly wished I could say goodbye and tell him how much pleasure he’d brought me through the years. I decided to break my agreement to never look into his past, convincing myself that Boudreaux had reneged on his end of the bargain first by dying while we were estranged.

I emailed the local sibling the gym owner had told me about, and went over my odd relationship with the guy I knew as Boudreaux. I sent the sibling several of my Boudreaux columns and said how lucky I felt to have ever crossed paths. The sibling asked if I’d meet to talk about the departed, while requesting that any information about his family be off the record. Of course, I agreed. I couldn’t wait.

I learned at the meeting that much of what I thought I knew about Boudreaux—things he’d told me about playing football at a PAC-12 school and doing a tour of Vietnam—was utter fiction. He wasn’t a war veteran or even a high school athlete. And his work life didn’t get much more exciting than construction and wholesale sales. I also found out that the rollercoaster relationship me and Unitas had with Boudreaux mirrored his relationships with his kin. The sibling suspected that the erratic behavior and occasional flat-out meanness came from mental illness that went untreated, and said dealing with him eventually grew too burdensome. At the time of his death, the sibling had been estranged from Boudreaux even longer than I was.

But our meeting, at a diner outside D.C. where I’d once met Boudreaux, was hardly all darkness. The sibling had no inkling about the Boudreaux character’s existence or his sports talk heyday, and thanked me for sending my columns full of his Dan Snyder–bashing lines.

“The stories reminded me that he could be the funniest man I ever met, before he was the biggest pain in the ass,” the sibling told me.

Then the sibling brought up a tale as unforgettable as any in the Boudreaux oeuvre.

“Did he ever tell you about the Jets jerseys?” the sibling said. “I know that one’s true.”

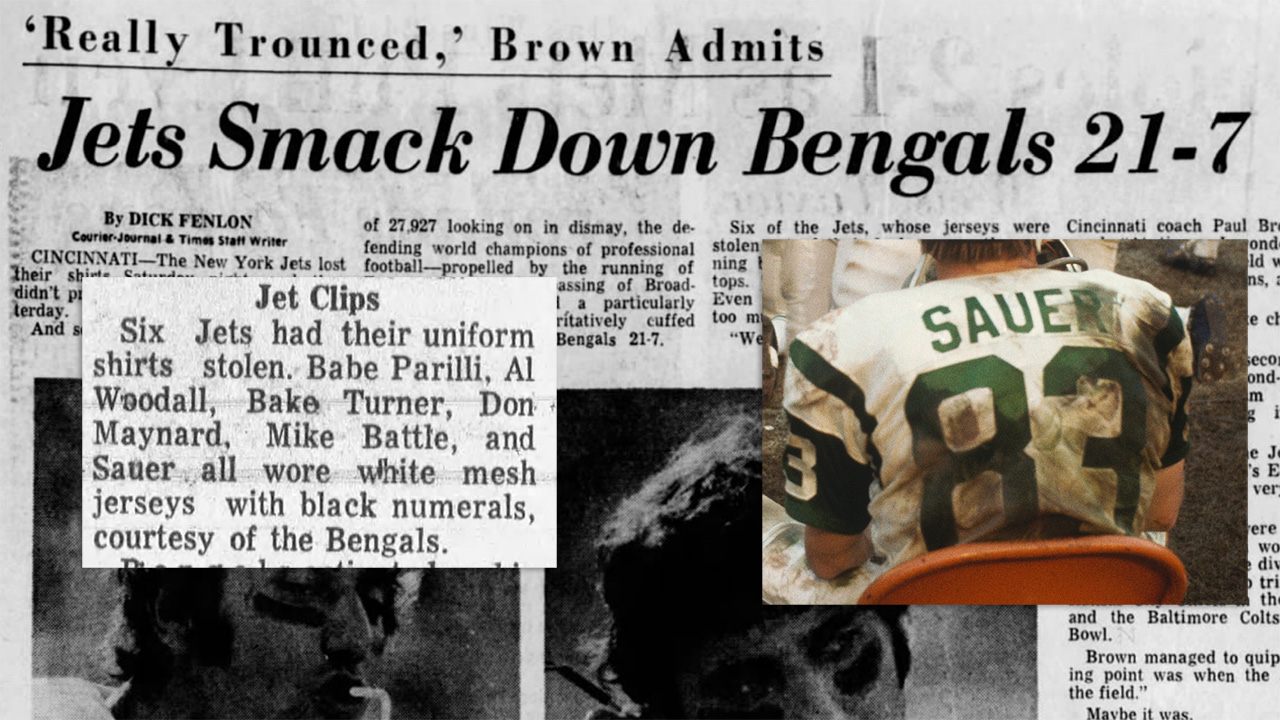

And what a tale it is. In the early morning hours of Oct. 12, 1969, somebody snuck into the visitors locker room of Nippert Stadium, then the home of the Cincinnati Bengals. The reigning Super Bowl champs, the New York Jets, were in town. The thief swiped several Jets jerseys off their hangers and fled.

The burglary created chaos. From the New York Times writeup of the fiasco: “Six members of the New York Jets wore white mesh Cincinnati Bengals jerseys with black numbers today after their uniform tops had been stolen from the world champions locker room at Nippert Stadium … It was the third time this season that [Jets receiver Bake] Turner’s jersey has been stolen. Joe Namath’s has been swiped twice, but the Cincinnati thieves missed it.”

Boudreaux’s sibling had heard about the thefts and the passel of Jets (Turner, George Sauer Jr., Babe Parilli, Don Maynard, Mike Battle and Al Woodall) having to wear the opponents’ jerseys, since that was the talk of Week 5 of the 1969 NFL season. Then Boudreaux came home days later with a pile of memorable memorabilia and a story behind it.

“He said he went in for [Super Bowl MVP and Jets QB] Joe Namath’s jersey but couldn’t find it,” the sibling said. “So he took the others." Boudreaux gave select friends and family members their pick of the litter, the sibling said, so George Sauer’s jersey stayed in the house for years. Boudreaux was never outed as the consequential thief.

That’s what I needed to hear. One more Boudreaux football story that made me howl. That’s how I want to remember the guy. RIP, Boudreaux.