All around the world, and especially in the United States, widening economic inequality, deep sociological divides, pathetic political systems, rapacious capitalism, and failing public institutions have stripped concepts like the common good, democracy, and progress of any broadly shared meaning. Untethered both from each other and a shared version of reality, citizens have divided themselves into distinct and mutually exclusive camps, experts say. At every level, on every imaginable topic, it is a matter of "us versus them." The word that generally gets used to describe this dynamic is polarization, and it's reflected across the fractured, dysfunctional American media landscape.

There is more information than ever out there, but it is nonetheless difficult to know things; news consumers, bombarded by opinions and variably factual facts, are left with their mouths hanging open like so many Mr. Krabses as the world spins around them. The diagnoses are easy to find, but often in conflict. Social media is bad for journalism. Disinformation is the real problem. Robust local news is the answer. There's simply too much news for readers to handle, or maybe actually there's the right amount, but it's being presented in the wrong way, or it's being presented in the right way but news consumers don't trust it. Or the right kind of readers trust it, and it's the wrong kind who must be won over. Or the wrong kind will never be won over, and so it's best to focus on those who can be reached. Throw a stick, and you'll hit a news organization that claims to be working tirelessly to solve one or several of these problems.

Semafor is one such organization. The news media start-up from former New York Times columnist and BuzzFeed Editor-in-Chief Ben Smith and former Bloomberg CEO Justin Smith—related only in their entrepreneurial spirit—finally went live Monday. As part of its launch, Semafor identified the biggest problem with media (polarization) and unveiled its plan to fix it (reduce polarization).

"Polarization is tearing at the seams of our societies," says the breathy podcast-voice narrator in Semafor's intro video, placing the blame for this not on any of the real reasons partisan animosity exists, or even the easy-target algorithms that tech companies like Facebook use to feed people news that drives conflict, but instead squarely on news consumers. Those consumers, we are told, "choose [news sources] that reinforce our beliefs because we love feeling right ... and feeling superior to the people who you disagree with."

Because Semafor has decided that the biggest problem in media is "polarization," and because they see that problem as driven by consumer choice, it follows that their solution would be found in—as the video put it in a mixed metaphor that alone would be disqualifying in a just world—"making a dent in the polarization of the media," also through consumer choice. The goal is to "solve certain significant news consumer frustrations," Justin Smith said in basically every interview he gave about Semafor's launch, adding, "The top of the list is polarization, bias, and social media distortion." The way to solve these consumer frustrations, Ben Smith wrote in his introductory post, is by giving the people what they want:

We take people seriously when they say they know that reporters are human beings—and experts in their beats—who have views of their own. But they’d also like us to separate the facts from our views. They’d like us to be humble about the possibility of disagreement. And they’d like us to distill differing views, and gather global perspective.

By choosing Semafor, the pitch goes, you will get facts, opinion, and opposing viewpoints. Not only that, they will all be clearly labeled as such, lest you get confused. By choosing Semafor, you will also be helping to reduce polarization. How that part happens remains unclear, but it has something to do with the choice that you will have made, as a consumer, to consume the right kind of news.

It also has something to do with rebranding the concept of news article. "We’re redesigning the atomic unit of written news, the article," Semafor trumpeted in another introductory post.

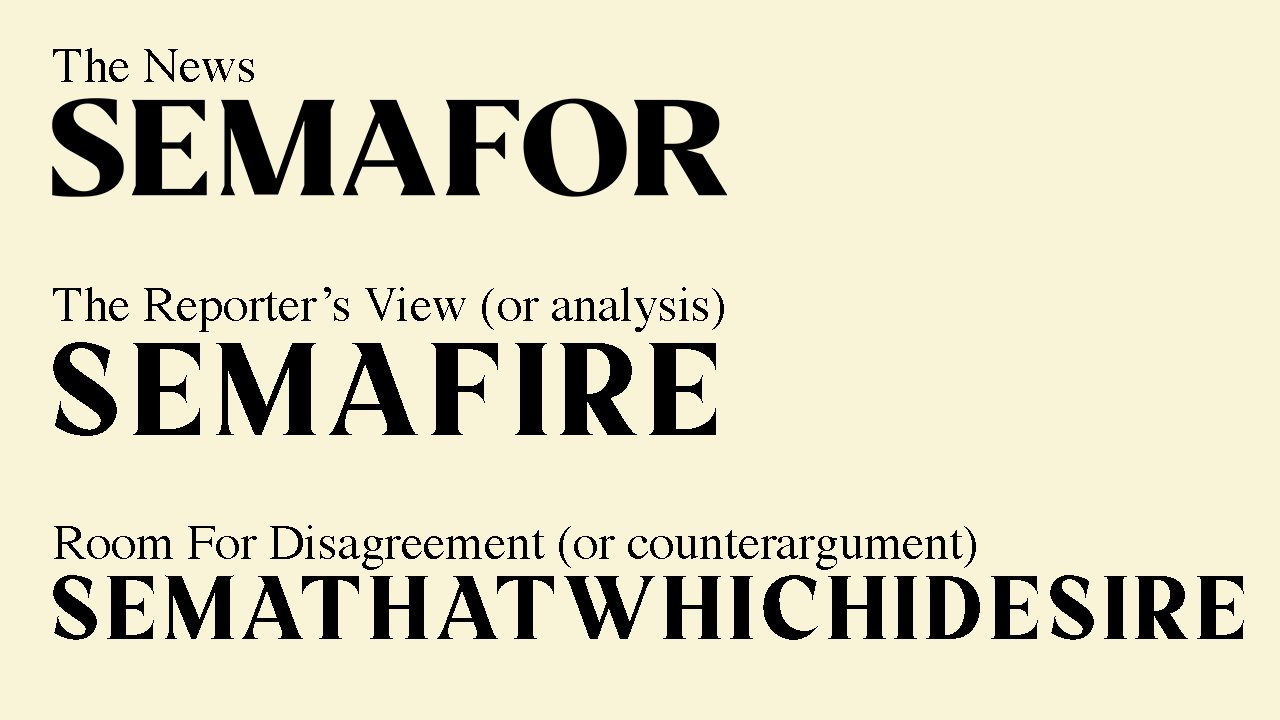

The redesigned atomic units of a Semafor article will be:

- The News

- The Reporter’s View (or analysis)

- Room For Disagreement (or counterargument)

- The View From (or different perspectives on the topic)

- Notable (or some of the best other writing on the subject)

If this new article format, which Semafor has dubbed—gag—the "Semaform," sounds more or less like the existing format you might find at any other traditional news organization, you're not wrong. Articles containing news, analysis, counterarguments, various perspectives, and links to other outlets' work are standard across the industry. The biggest innovation here seems to be adding patronizing subheadings. Take this article by reporter Bill Spindle, about how the upcoming global climate change conference could be a bust. In the "News" section, the article says:

Countries in the Global South have lost patience with the promises of their northern counterparts, who pledged to provide more than $100 billion in funding to them to build clean energy sources and adapt to increasingly harsh weather patterns.

“Climate finance isn’t meeting the scale that is required,” Kevin Chika Urama, chief economist at the African Development Bank, told Semafor. “We’ve been talking about $100 billion to address an existential threat of climate change to the world and we haven’t been able to meet that. And yet within two years... the world mobilized in fiscal measures [worth] over $17 trillion to address the COVID impact.”

In the section called "Bill's View," the article reads:

Developed countries are likely to fail in any effort to spin their developing counterparts, especially since once again they’ll show up without having fulfilled a commitment made more than a decade ago to provide the $100 billion annually starting in 2020. They’ve also clashed over whether the Global South should be compensated for past damage and losses related to climate change.

Further undermining efforts at the meeting is the lack of any direct coordination between the U.S. and China, the two biggest contributors to global warming. In an interview recently, U.S. climate envoy John Kerry told me he didn’t expect that situation to change before COP27. China shut down climate discussions after U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan in August.

Is this analysis "Bill's view," or just the reality of where things stand? What is gained by crediting this recitation of the consensus specifically to Bill? Is there even a trace of an opinion in here? The "Room For Disagreement" section is even worse. There's no acknowledgement of the underlying obstacles facing the world's effort to stop climate change; instead, it's Biden administration spin about how progress really is being made. Not to pick on this article in particular, which is representative of what you'll find on the site, but it seems that what we have here is just a typical news article with some silly subheads. Columbia Journalism Review's Jon Allsop registered a similar criticism in his review of Semafor's format:

My biggest problem with the Semaform, at least so far, is that it seems inflexible, particularly when it comes to the “reporter’s view” section. Some of the Semafor stories I read yesterday offered what was clearly analysis in this section, though it rarely seemed particularly pointed or personal and sometimes didn’t read much like a point of view at all, but rather a continuation of the reporting above; indeed, at least one story contained sources’ quotes in this section. If the separation of facts and analysis is supposed to aid clarity and boost trust, then the two need to be consistently distinguishable; where they blur together, the separation just adds more confusion.

Given that it is sponsored by the Knight Foundation and funded to the tune of $25 million by wealthy individual donors including crypto billionaire Sam Bankman-Fried, The Atlantic owner David Bradley, and fellow media mogul Jessica Lessin, it's hard to see Semafor operating anywhere but well within the bounds of established norms. Semafor clearly wants to be seen as straddling divides—those between progressive and conservative, new journalism ethics and traditional conventions, fact and opinion. In content, scope, and tone, however, its output so far is basically identical to that of any number of existing news organizations.

That's not to say Semafor is doomed; its doofy format has already been heralded from some predictable corners as novel and promising. But the discrepancy between Semafor's lofty ambitions for saving media by tackling polarization with a revolutionary news article template and its actual product, which is a bog-standard reproduction of what already exists, is more than an indictment of the thought leaders in charge of Semafor. It also exposes the hollowness of discussions about media polarization. There is a powerful constituency for the idea that the problems of the world are informational, arranged by degrees of knowledge, bounded by human nature, and require—and this part is always implicit—no alterations to the basic dispensation. It is the people who believe this, a group that includes but is not limited to the type of moguls who fund startup news organizations, that Semafor seems best built to serve and flatter.

There are bigger questions looming over all of this. Can media actually do anything to "reduce polarization"? Is that even a worthwhile goal? Aren't popular movements—the labor movement, the Civil Rights movement, the anti-war movement—built on radicalizing people, recruiting them to a polarized field? There's an argument to be made that, in fact, less polarization is the opposite of what this moment demands. As politics writer Osita Nwanevu wrote in The New Republic in 2020, "To fight polarization, we’ll have to get much more polarized. The only way out is through." Nwanevu wrote:

Absent a radical shift in the right’s priorities, the only way to depolarize our institutions is to win and win big against those who want to keep them undemocratic, protecting the right from the moderating influence more competitive elections could have. Those victories will depend on reformers successfully marshaling the forces driving group identity, rather than assuming the balance of power in America has been set primarily by immutable psychologies. The way forward lies in convincing Americans not to retreat from national politics but to think even more broadly and abstractly about where this country ought to go.

I find this argument convincing primarily because it speaks to the reality of building and wielding political power; for all the obvious reasons, it wouldn't appeal to successful establishment types like the Smiths and their backers. But even if you think polarization is a problem to be solved, and even if you think media does has a role to play in helping fix it, it's important to be clear-eyed about what effective reforms might look like.

In media, the most promising ideas are aimed at structural change and overhauling how media is funded and operated. In his 2020 book, media scholar Victor Pickard calls for "vastly increased funding for public-interest reporting and public media, newsrooms that are run democratically by journalists and members of the community, and breaking up or strictly regulating monopolies such as Google and Facebook." In comparison, Semafor's dinky plan to publish duller, subhead-laden versions of whatever you can read in the Times or Politico is the sort of unserious half-measure that would only sound good to the class of people who write checks for this kind of thing.

In that way, at least, Semafor's pitch makes sense. If you were a billionaire or millionaire for whom the status quo is working out just fine, but who also finds some of the more ominous stuff in the culture to be disturbing, would you want to hear that the unpleasant divisiveness in the world is due to things like skyrocketing inequality, financialization, and other macro forces which most certainly serve your personal interests? Or would you be more inclined to hear great promise when a couple of media-famous business types stroll into your conference room with a different pitch, one that casts "media polarization" as the sickness, not the symptom? The dire state of things has nothing to do with you. It's because of all these damn news consumers, who just want to have their beliefs reinforced so they can feel superior. The good news is that we can fix them, and everything else, with your generous support! Dangle an indulgence like that in front of a few vaguely guilty rich people who care about looking like part of the solution to a problem they refuse to see, and suddenly you've got enough cash to start a media company.

The people who are most invested in reinforcing their own beliefs aren't the ones consuming the news, but the ones making it.