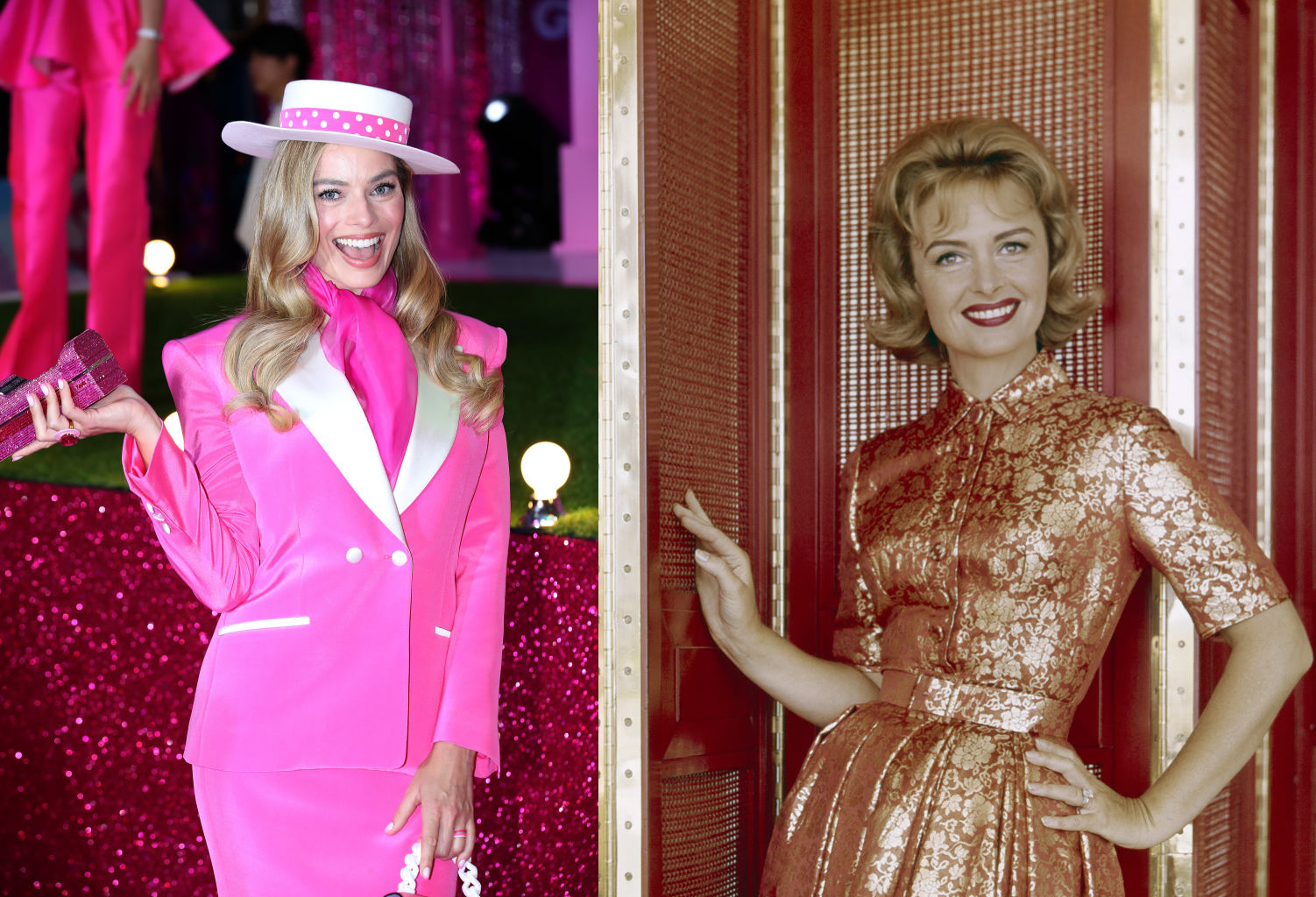

This past year felt especially blessed with brilliant actresses telling a wide range of women’s stories. Month after month, you could go to the movies and see women confronting genocide, environmental doom, the ways men attempt to take ownership of our desires, the fault lines of a marriage, how little we control our own destinies, and being so catastrophically horny you start a girls-only fight club at school. But no film made more money or dominated more conversations than Barbie, which received critical acclaim and a gargantuan box office take for director/co-writer Greta Gerwig and star/co-producer Margot Robbie.

Barbie’s place in the culture—and the cultural discourse—has only been magnified since the announcement of Oscar nominations last week, which put the film up for eight awards, including Best Picture, but not Best Director for Gerwig or Best Actress for Robbie. Some people got very mad about these so-called snubs. Ryan Gosling put out a statement almost apologizing for getting a nod as a supporting actor, writing “to say that I’m disappointed that they are not nominated in their respective categories would be an understatement.” (He declined to say which nominees he thought should be replaced.) Hillary Clinton, of all people, not-so-subtly compared the nominations with her experience in 2016 winning the popular vote but losing the electoral college to a parody of angry male incompetence. And even those who should know better, like Pulitzer-winning Los Angeles Times critic Mary McNamara, took potshots at other experiences of womanhood to defend this film. “If only Barbie had done a little time as a sex worker,” she began. “Or barely survived becoming the next victim in a mass murder plot. Or stood accused of shoving Ken out of the Dream House’s top window.”

That specific sort of outrage—not “the men got their way” but “the wrong women were honored”—is where the Barbie craze takes a sinister turn. Framing the artists who have reached the top of their profession as perpetual and stereotypical victims makes no sense. No woman in the industry is a threat to them. Why is Gerwig, who’s now in the blank-check zone, considered a snub and not someone like Emma Seligman, who crafted just as strange and funny a world for Bottoms? Why is Robbie, whose casting the movie itself undercut at a key moment of emotional vulnerability, the one who needs defending and not Greta Lee, whose performance in Past Lives quietly stretches to hold her character’s deep well of curiosity and longing?

The answer, as stated by Clinton, McNamara, and many, many others, is that Barbie made more money and has more fans than any of those other films, so it deserves the most distinction. But that doesn’t work for me. A culture that holds Barbie as the film by and for women works only for that mainstream majority, and pushes out everyone else. That path leads to a dismissal of our history and a ceiling on our potential.

I’ve been fixating on the big archetypes of womanhood all winter—in particular one that debuted on television almost simultaneous with the sale of the first Barbie doll. When I tested positive for COVID on Christmas Day, I entered the world of The Donna Reed Show. That may sound like a dazed choice landed upon by a head congested with snot, but I had my reasons. I will go to bat for It’s A Wonderful Life, which had been playing on TV all week, as the single greatest movie of all time, and Donna Reed’s Mary Bailey is the heart and soul of that film, projecting idealism, generosity, and a streak of mischievousness that sticks around even as her husband spirals. “He’s making violent love to me, mother!” remains a sudden shock of hilarity that gets better every December.

For all my life, Donna Reed was only ever Mary Bailey, and what I’d heard about her other work—specifically The Donna Reed Show, her hit TV program that ran from 1958 to 1966—wasn’t flattering. The show, in the popular imagination, is symbolic of a repressed post-war white America, where the nice mother cleans the nice house and cooks nice meals for her nice kids and her nice husband. In large part because her name was on the show, as opposed to the numerous other housewives on TV, Donna lives on as a counterpart to Betty Friedan, drafted as a model for the kind of marriage that women felt trapped by. In a 1983 Congressional hearing on “the breakdown of the traditional family unit,” one witness specifically referenced Donna Reed and Father Knows Best, then argued “the idealized image of the suburban American wife created and sustained during the 1950s by the commercialized media was clearly inadequate. It proved susceptible to erosive and partly sound critiques such as Betty Friedan's 1963 book The Feminine Mystique.” (For what it's worth, Reed seemed to live most of her life as politically conservative as her old co-star Jimmy Stewart, but later made headlines as a strident anti-Vietnam War activist once her sons came of age to be drafted.)

For many millennial women, I suspect, it’s an early episode of Gilmore Girls that crystallized Donna Reed’s image. The episode “That Damn Donna Reed” starts with Rory and Lorelai eating pizza on the couch while watching the show for the sole purpose of making fun of Donna’s ridiculous perfect lifestyle. Dean, Rory’s all-American boyfriend, stands up for Donna and what she represents, and this eventually leads to a conflicted Rory trying really hard to be Donna for him for a night, prancing around in a fossil of a dress and offering up a kaleidoscope of homemade cooking. They come to an understanding at the end, but the lingering message is that the heroines of this television show are both more evolved and more “real” than the mother/wife cutouts that once dominated their medium.

When I actually watched The Donna Reed Show, however, it did not feel beneath me. After the initial shock of the slower tempo and lower stakes of that era of TV, I very quickly realized I admired plenty about Donna’s character and performance. She may not be Lucille Ball, exactly, but rather than a staid diorama of old-fashioned American life, the thrust of the show is an intelligent woman coming up with clever solutions to her particular problems. There’s an episode where Donna causes a proto-feminist stir on the radio by illuminating all the hidden work that housewives do, and it ends with her slamming the door in the face of a guy who refers to that radio woman as a “screwy dame.” There’s one where she feels pressure from the community to buy an expensive new dress, because she wears the same one all the time, and earns lavish praise when she gives in, only to reveal that she just modified her old one on the cheap. And then there’s a sort of charming neuroticism that makes her less impeccable than Rory Gilmore implied, like this amusing bit of food organization in the freezer:

Of course, beyond the subtle degradation of, for example, a husband who can’t provide food for himself and his son for one measly weekend, there are regular moments that stick out as dated or frustrating. There’s outright sexism—often when her doctor husband’s patients complain about their wives (“Our calmness and stability get to them [women] after a while”)—though the men are usually proven wrong in a gentle way by the end of the episode. More bizarrely, there are little restrictions on Donna’s freedom of expression that can make theirs feel like an alien civilization: when she apologizes for wearing jeans when company drops by, or when she dyes her hair and everyone who sees her treats her like she got a neck tattoo. Most importantly, there’s the unspoken world outside what’s on the screen—Americas beyond straight, white suburbia that no show of this time ever liked to consider. Some revisionist interpretations emphasize Donna’s decision-making on-screen and her producing role off-screen as forgotten elements that make the show more progressive than it seems, but it’s still unignorable that her wonderful TV life was gatekept by larger hatreds embedded in the pillars of American society.

It makes perfect sense that a modern woman watching The Donna Reed Show wouldn’t connect with the life lived by its protagonist. It’s also understandable that the contemporary wives and mothers who suffered from prejudice, abuse, depression, or a general lack of fulfillment in their lives would tune in and consider it a lie, or a trap, or propaganda. But The Donna Reed Show offers an appeal that survives into 2024: She lives unaccountable to a boss at a 9-to-5, enjoys time to cultivate friendships and raise her healthy children in a beautiful home, and has her financial needs met by a person with whom she shares a mutual love. When the option of a single-income household, supporting multiple kids without giant sacrifices, or even just owning property feels out of reach for large swaths of young people facing stagnant wages, Reed has the superheroic allure of high-quality escapism.

That’s where enjoying the show can start to feel like biting into a poison apple, because there’s a whole right-wing movement dressed up in a pitch for making those goals possible again. The tradwife trend, the Retvrn crew, whatever terms you want to use—it’s a product that influencers sell to those online who aspire to a retro-flavored ideal of domestic life. It can be packaged as a form of resistance to capitalist hierarchy, and on a gut level there’s something satisfying about the idea of quitting your job to produce value only for your loved ones. But as Gaby Del Valle wrote in The Baffler last year, the pretty dresses and elaborate meals often mask the white male supremacy that dominated the times that this whole endeavor attempts to pay tribute to:

Ayla Stewart, the woman behind the once-popular trad blogs Wife with a Purpose and Nordic Sunrise, has said that “black, ghetto culture” will lead to the “cultural destruction” of Utah and Mormonism. (Stewart, who calls herself the “most censored Christian mother in America,” claims she has since “retired from political commentary” after “a strong prompting of the Holy Spirit. 🙏.”) Lori Alexander, who promotes traditional gender roles on her blog The Transformed Wife, has written about how an “abundance of female preachers” are waging “war against men,” white men in particular. These women preachers, Alexander writes, do not “teach biblical womanhood” and therefore “disobey God.”

Even for those who aren’t overtly hateful, this is a cloistered lifestyle that can’t function without the people kept outside the town limits. In The Donna Reed Show, that would be everyone who wasn’t white enough, straight enough, wealthy enough, Christian enough, traditional enough to fit into the world of this family, even if it’s what those outsiders desired. There’s nothing inherently evil in cooking or cleaning or not earning a salary, but endorsing Reed as an icon of femininity makes me worry that I’m unwillingly lending my participation in the massive conservative project aimed at rolling back the rights of those who didn’t have their own popular sitcoms. How could one strive for that life without being touched by its venom?

It’s easy to buy into a narrative of progress—after all, every product sold is “new and improved,” not “older and worse.” This applies to art, too, when we’re not aware of our own history: Sam Smith becomes the first openly gay Oscar winner; every poem by a newly out trans person becomes The First Trans Poem. I think that’s partly why the fundamental relatability of Donna Reed on TV surprised me as much as it did. History is more circular than it’s comfortable to admit. People stay the same, for better and for worse. And it’s especially tough to accept that, after 65 years, Barbie serves a slightly different flavor of the same tricky identity questions that Donna Reed does.

I learned pretty quickly to temper my misgivings about Barbie in real-life conversation, but I mostly just liked it for the jokes. (The one about the Kens only knowing how to build a wall vertically makes me chuckle as I’m typing right now.) The actual heart of the film felt strangely old-fashioned; nothing like this year’s movies about women I’ve truly loved, which either reckoned with sins of the past that the establishment wasn’t ready to deal with, or opened brand-new doors to better futures. Barbie’s core theme—the Kafkaesque contradictions of being a woman in a world of men, voiced bluntly by the Oscar-nominated America Ferrera’s character—wouldn’t feel out of place on an episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show. Its darker plot elements, depicting a warped dream world where women are programmed servants of men, are ripped straight from The Stepford Wives. Its cultural reference points are New Hollywood and ‘90s rock. And even its conflict’s big solution feels stuck in the old era of consciousness-raising. That genre of feminism is closer to Donna Reed’s time than my vision of womanhood today.

Barbie was a gender-affirming blockbuster that reflected its audience’s “buried, unspoken” problem and then gave pride and comfort to many of the women who paid to see it. That’s an impressive feat. But what shocks me is the number of women—especially younger women—who experienced it as something ground-breaking or revolutionary, rather than well-rendered entertainment.

When Ferrera thanked Gerwig at the Critics' Choice Awards, it was “for proving through your incredible mastery as a filmmaker that women’s stories have no difficulty achieving cinematic greatness and box office history at the same time.” I could have sworn she copied word for word the praise that followed the success of Wonder Woman, but that kind of hyperbole—“Wow, finally, a woman made a hit movie!”—is central to the story that Barbie’s biggest fans tell. It’s true that no woman, as a solo director, has ever earned more money at the box office, but presenting Barbie as unprecedented ignores the hugely popular works of directors like Penny Marshall, Barbra Streisand, Nora Ephron, Nancy Meyers, Amy Heckerling, or Patty Jenkins, and it plays the film industry as a zero-sum game in order to keep the money all in one place. The elevation of this director as an unprecedented legend obscures the real question: Why, still, is only one female filmmaker at a time invited to eat at the major studios’ table?

Even when the aesthetics of Barbie—the overwhelming bubbliness and interests of women that were often ridiculed or minimized by men—are celebrated by its fans, it can lead them to a place with weirdly strict definitions of femininity. In Barbie, men like The Godfather and Pavement and the women who listen to them talk about those interests are ditzy pretenders. These are harmless jokes about stereotypical gender differences until the arbitrary distinctions start going viral outside of its universe. Being a woman means you can’t do math. Being a woman means you think just like Taylor Swift. Being a woman means you love to enjoy DIY charcuterie by yourself. When I told my mom that Ferrera’s monologue felt kind of empty to me, she defensively responded, “Maybe you haven’t lived it enough.”

At best, these in-group/out-group games are overcorrections to years of condescension, but at worst, they’re a form of gender essentialism actively redefining the boundaries of womanhood to conform to the examples of its richest, straightest, whitest, most traditionally beautiful representatives. For the benefit of Mattel, which seems obsessed with using Barbie as the vanguard to saturate its other brands across the culture, it turns womanhood into a closed circuit one has to pay to enter, albeit with a slightly different pitch than before. Whereas those obsessed with ‘50s-themed propaganda focus on womanhood as a physical distinction that manifests in behavioral codes, this more liberal framework centers womanhood as a feeling—but only the one. Take this passage from McNamara, which not only seems to deny womanhood to sex workers, but defines a girl’s own orgasm as inextricably male:

The “what was I made for” themes are remarkably similar, but “Poor Things” is, in many ways, the male gaze on a plate — what exactly are we to make of the sight of a full-grown woman with the brain of a child discovering the joy of orgasm? Or her literal childlike appreciation for sex? Or her questionable, if more mature, decision that sex work is the obvious, and enjoyable, answer to her need for sex and money.

Perhaps a sex scene or two would have convinced academy voters that “Barbie” was just as affecting and creative a story of female empowerment that required the same high level of direction and acting.

It’s no surprise that sex-negative feminism would find a heroine in a character that famously lacked genitals. But it’s amazing how, generations since the debut of The Donna Reed Show, the cult of personality around Barbie raises nearly the same question for so many women: “What does it mean for me if I can’t fit into it?” Rather than an expansion of what’s possible for women, the intense defensiveness around Barbie can feel like a narrowing of the entryway, turning a blockbuster film into some kind of referendum on a proper woman’s life—presenting an understanding of that film as a reward for having weathered the most “authentic” kind of womanhood.

Neither Barbie nor Donna Reed light a path forward for women who understand the violence and aggression inherent in the systems arrayed against them. Profit-focused mass culture never will. It’s not worth our time, and will never repay our efforts, to go to bat for it. The thing on the screen may be entertaining, but it’s not about us. We’ve all lived it enough to know.